Who Was Elizabeth Fairfax?

Introduction

The 17th–18th century manuscript recipe book at the heart of this digital exhibit is a fascinating document of early modern domestic life. Created and passed down during a turbulent time in English history, we should maybe not be surprised that some facts about the book are ambiguous today. First off: who even wrote it? Whose hands recorded these diverse, sometimes strange recipes? Students, archivists, and librarians at Mason have grappled with that question. This essay will present the best currently known evidence for its answer.

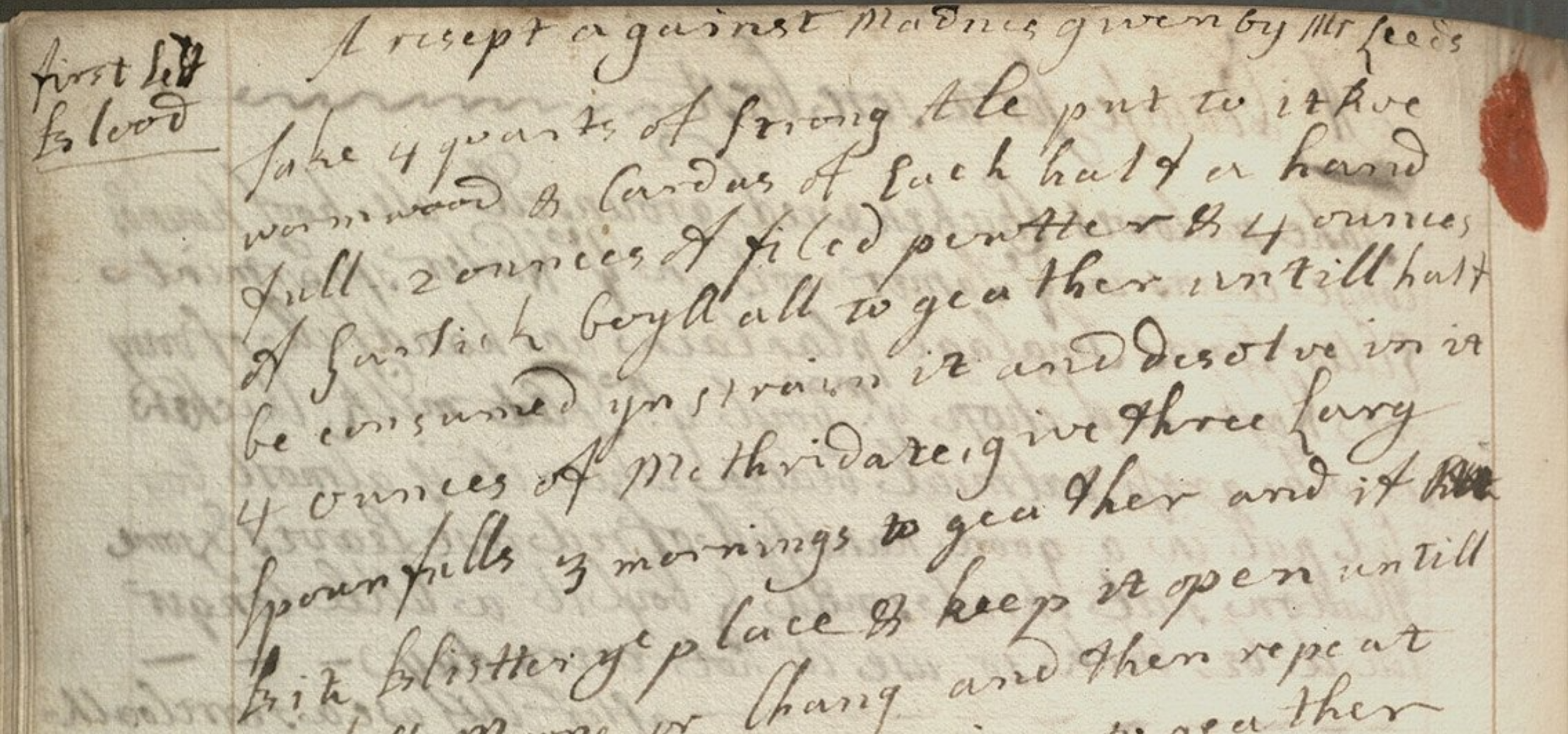

Although apparently the product of several people writing over the course of generations, judging both by the span of dates listed (1694-1795) and the multitude of distinct handwriting styles, the Fairfax-Spencer Family Recipe Book has traditionally been attributed to Elizabeth Fairfax as its primary owner. And this is for good reason: just above a recipe “for keeping shoes black,” the first page features the title, “Elizabeth Fairfax / Hir Booke [Her Book] 1694.” Researchers opening the book are immediately met with this claim to ownership, and still today it is known as the Elizabeth Fairfax Cookbook by Mason Libraries’ Special Collections Research Center, its archival repository.

But who was she?

Elizabeth Fairfax of Steeton

Thanks to the recent discovery of new sources, as well as an extensive review of the recipe book, we now know this Elizabeth Fairfax (1670-?) was baptized in 1670 at Steeton Chapel in Yorkshire, England, a daughter of William Fairfax (1630-1673) and his wife, Catherine Stapleton (?-1695). (Maiden names are used here to clarify families of origin.) This branch of the Fairfax family centered around the Steeton and Newton Kyme estates in Yorkshire. Elizabeth married Thomas Spencer (1670-1703), esq., in the early 18th century and subsequently lived at either Attercliffe Hall or Bramley Grange, Spencer family estates also in Yorkshire. Together the couple had one son, William (Pedigree np; Burke 389; Markham 35, 53).

How do we know the Elizabeth Fairfax from our book had anything to do with the Spencer family? Surely, there were several women named Elizabeth Fairfax living around this time in England. Might ours have been another one?

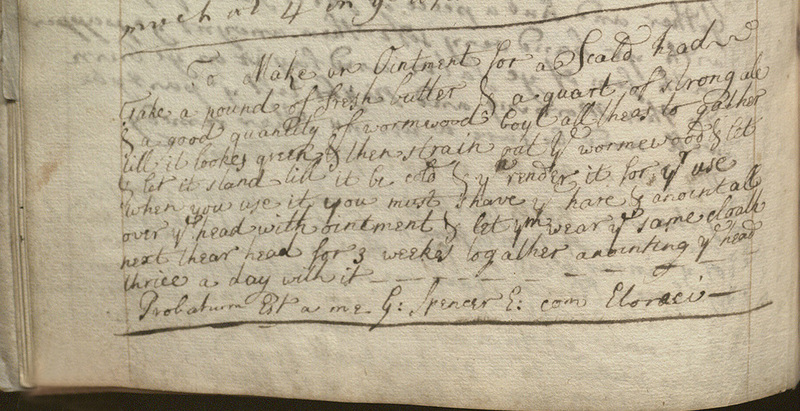

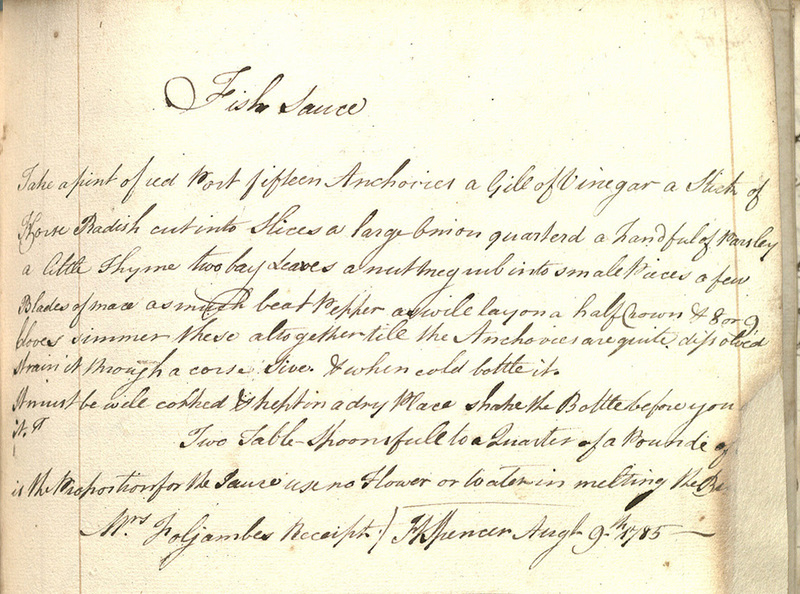

This link between the Fairfax and Spencer families is confirmed in the recipe book itself since, significantly, some Spencers sign their own names. On the first page, the recipe for keeping shoes black ends, “Probatum est a me [It has been tested by me]: G. Spencer / 1773.” At least one other recipe is signed identically by the same person (“To make an ointment for a scald head”). An “H. Spencer” signs the recipe for “Fish sauce,” although it is attributed as “Mrs. Foljambe’s receipt”; this is noteworthy, for Elizabeth and Thomas’ granddaughter, Sarah Spencer, married Thomas Foljambe, esq., providing further evidence of the book’s provenance within this family (Markham 132). It is not currently clear whether G. Spencer and H. Spencer were direct descendants of Elizabeth and Thomas or other family members.

The presence of Elizabeth’s maiden name in the title of course suggests that she had not yet married in 1694. This is corroborated by surviving pre-nuptial agreements between Thomas Spencer and Robert Fairfax, Elizabeth’s brother, dated to March 26, 1701, today in the Spencer family collection at Sheffield City Archives (Pre-nuptial np). Elizabeth and Thomas must have therefore married sometime between March 1701 and Thomas’ death in the summer of 1703 (Probate np; Burke 389; Markham 57). It is tragic that Elizabeth’s marriage was cut so short by her husband’s young decease, although in view of early modern life expectancies this was perhaps not uncommon.

We are less sure when Elizabeth died. One source claims she died in 1708, whereas her brother Robert’s will evidently mentions her as alive in 1721 (Markham 277). A draft of Elizabeth’s will, written in her own hand, is dated even later to November 22, 1729. Signed “Eliz Spencer,” this will mentions a “dr [dear] sister Alathea Fairfax" (Draft will np). Alathea (1672-1744) was in fact another daughter of William Fairfax and Catherine Stapleton (Pedigree np; Markham 35). Whatever else may be unclear, then, we can at least be confident that this “Eliz Spencer” is the same Elizabeth Fairfax from our recipe book, and that she died sometime after November 1729.

Like the recipe book, this draft testament offers a glimpse into the domestic material culture of early modern women. Among other personal property left behind, Elizabeth bequeathed her bed and bedding, an inlaid chest of drawers, "a Couple of olde silver spoons," a black silk hood, an apron, a silver teapot. To her sister Alathea she left a large silver coffeepot, a matching scalloped plate, a velvet hood, and a scarf. Although the recipe book is not mentioned in this will, Elizabeth bequeathed "all the rest of my personall Estate to be Equally devided between those Twin Children Margaret & Elizabeth Spencer Daughter to my Dr [Dear] Son Wm [William] Spencer," and it is possible the book was thus among that property inherited by her grandchildren (Draft will np).

Related Fairfaxes of Steeton and Newton Kyme

Lady Frances and Sir William Fairfax

Elizabeth and her siblings were grandchildren of Sir William Fairfax (1610-1644) and his wife, Lady Frances Chaloner (1610-1692), two rather notable ancestors. Lady Frances is commemorated in an inscription on the first page of the Fairfax-Spencer Book, just above the title:

Frances Lady Fairfax Daughter of Sr Thomas Chaloner was baptized Febry the 10th 1610 & dyed Janry the 2d 1692. She was sixty year [sic] as Mrs. of Steeton as appears by her Armor Set up... over the hall door / 1633.

Frances, as this inscription notes, was a daughter of Sir Thomas Chaloner the Younger (1563/4-1615), a courtier and scientist (Westby-Gibson). Two of Frances’ brothers were politicians, James (1602-1660) and Thomas Chaloner (1596-1660), the latter being a regicide (Scott “Chaloner, James”; Scott “Chaloner, Thomas”). William and Frances married in 1629. Although he was knighted by Charles I, William—like Frances’ brother Thomas—took up the Parliamentarian cause against the king, becoming an officer during the English Civil War. He eventually died at the Battle of Montgomery in 1644 (Hopper). Slightly later, Thomas Chaloner would be a signatory to Charles' death warrant.

After Sir William died, fellow soldier John Meldrum petitioned the government requesting financial assistance for Lady Frances, “being left with many Fatherlesse Children & much behind in her husbands [sic] personal entertainments” (Certificate). It seems unlikely that Frances was ever directly involved with our recipe book, since she had already died by the time the title was written.

Robert Fairfax

Elizabeth’s brother Robert Fairfax (1666-1725) was a naval officer during the Nine Years’ War and the War of the Spanish Succession, eventually receiving the rank of rear admiral. After retiring from the navy, he was involved in the municipal governance of York until his death. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that Robert "gained a posthumous reputation arguably out of proportion to his achievements," due to "the chance survival of his papers... when those of many more prominent and interesting officers disappeared." This was also due to "the subsequent decision by Sir Clements Markham to make these the basis of a slight and fanciful biography, published in 1885. Fairfax attracted more mixed opinions from contemporaries" (Laughton). However true this assessment may be regarding the value of Markham's biography, the book has nonetheless been important here in verifying certain familial relationships.

Conclusion

Even with more information at our disposal, much is yet unknown about the book. How many people in total contributed? Can we identify distinct individuals, or even Elizabeth’s own hand, by cross-referencing the recipes’ handwriting to surviving manuscripts from the Spencer family collection in Sheffield City Archives? Might we glean more insight into the family’s history or even the broader sociocultural history of early modern England from these recipes? New questions and revelations aside, the book remains indelibly tied to the name Elizabeth Fairfax. It is by this name that hers and her family’s recipes—ranging from lemon cakes to snail water to the powder of sympathy—have survived into the 21st century.

Written by Gavin Thibodeau (2025)

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Certificate for Lady Frances Fairfax of Steeton, West Riding of Yorkshire. 21 September 1644. Entry book: letters received. SP 21/16, folios 257-8. The National Archives, Kew, UK. Transcription available at https://www.civilwarpetitions.ac.uk/certificate/the-certificate-for-lady-france-fairfax-of-steeton-west-riding-of-yorkshire-21-september-1644/. Accessed on April 4, 2025.

Draft will of Elizabeth Spencer, widow. 22 November 1729. Spencer Family of Attercliffe and Bramley Grange, Braithwell, West Riding of Yorkshire. BGM/81. Sheffield City Archives, Sheffield, UK.

Pedigree of the family of Fairfax of Walton, Denton and Steeton. c. 1600s. Spencer Family of Attercliffe and Bramley Grange, Braithwell, West Riding of Yorkshire. BGM/179. Sheffield City Archives, Sheffield, UK.

Pre-nuptial settlement – Thomas Spencer of Attercliffe, esquire, to Robert Fairefax of Steeton Hall, esquire, and Gilbert Berry of Linwood (Lincolnshire), esquire. 26 March 1701. Spencer Family of Attercliffe and Bramley Grange, Braithwell, West Riding of Yorkshire. BGM/2/1. Sheffield City Archives, Sheffield, UK.

Probate copy of the will of Thomas Spencer of Sheffield, gentleman. 17 June 1703 and 24 July 1703. Spencer Family of Attercliffe and Bramley Grange, Braithwell, West Riding of Yorkshire. BGM/78. Sheffield City Archives, Sheffield, UK.

Secondary Sources

Burke, John. A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 2. London: Henry Colburn, 1836. https://archive.org/details/heraldichistory02burk/mode/2up. Accessed on April 4, 2025.

Hopper, Andrew J. “Fairfax, Sir William.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

Laughton, J. K. “Fairfax, Robert.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

Markham, Clements R. Life of Robert Fairfax of Steeton. London: Macmillan and Co., 1885. https://archive.org/details/cu31924027986722/mode/2up. Accessed on April 4, 2025.

Scott, David. “Chaloner, James.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

___. “Chaloner, Thomas.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

Westby-Gibson, John, revised by Kenneth L. Campbell. “Chaloner, Sir Thomas, the younger.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.