Recipe Books & Women’s Knowledge

What Are Recipe Books?

Suppose you’re at home and aren’t sure how to make a certain dish, cure some ailment, or solve a household problem. In our modern age, we can get informational assistance from a plethora of sources, digital or personal. It has never been easier to get an expert’s opinion or instructions on how and why something should be done. However, in the 17th century in Western Europe, practical knowledge was often assembled into recipe books, also called receipt books or cookbooks. Curated by the women of the household, they were collections of ingredients & procedures needed to address problems of all kinds - “Not only was the housewife ultimately responsible for feeding her family, including preparing for winter and periods of scarcity, she was also the family’s and community’s main medical authority” (Kowalchuk, 19). These responsibilities required skills in botany, chemistry, anatomy, medicine, and other scientific fields, placing many of these women on equal authoritative ground as the educated men of the time.

These women were responsible for the maintenance of generational knowledge via these books, not only through learning from women of the past and their present contemporaries, but by training their successors as well. And not only did these reference texts need to be kept up to date, but they also needed to be explicable to others to ensure their usage beyond the original author’s lifetime. The women of the household, therefore, needed to be able to read and write to effectively carry out these responsibilities. In addition, there is evidence that the women refined elements of these recipes, like appropriate dosage for children versus adults, (like in "Feavors, to asuage & to Cool the Spirits or blood") a process that would have required experimentation and analysis. Extant cookbooks not only serve as eminent women’s research and scholarship, but as typically collaborative works that we can examine to unearth how women built up systems of knowledge that shaped their worlds.

Refined Over Generations

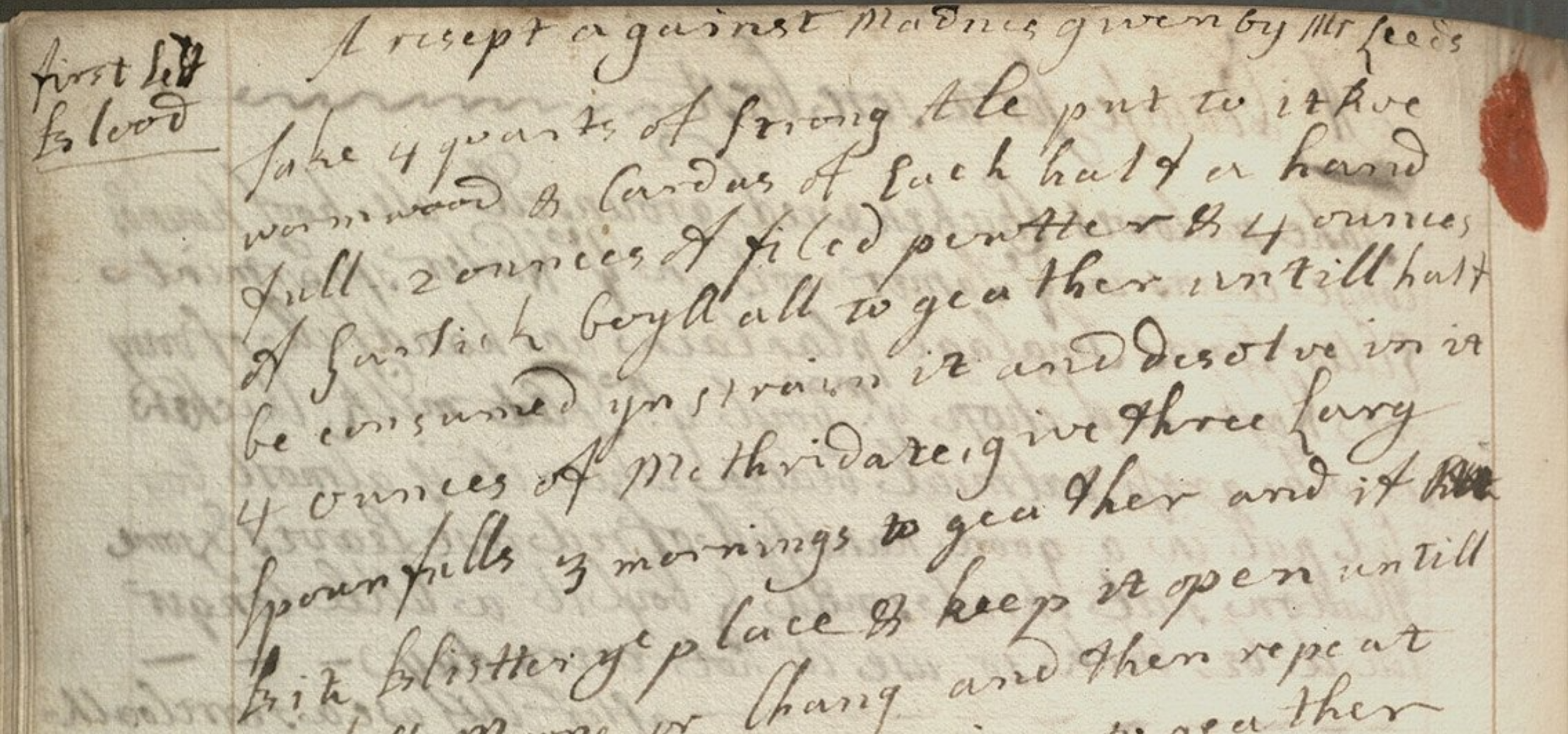

We know that more people than just Elizabeth Fairfax wrote in this book. Throughout, we can see examples of different handwriting and marginalia on top of prior recipes offering opinions and adjustments (like in “For sore nipples”). These marginalia are proof that the whole book was consistently viewed & reviewed over time, and that the act of alteration was not only tolerated but essential as new generations offered their insights. Women of the 17th century were more educated than popular stereotypes might portray and the solutions they found were cross-examined and tried as scientifically as any other practices of the time.

Additionally, there are many entries which are credited to other figures within the community, and even some that are visibly woven in from other publications (“The best Method to Clean: BRAWN"). Contributions could have been brought by visitors to the house, by family members retrieving discoveries from their ventures out, or by other recipe book writers sharing their research (Laroche). Even though these women took primary stewardship of assembling these texts, we can truly hold up recipe books as reflections of full communities’ practices and scientific understandings from the time period.

What Isn’t Written, But Known

It is worth remembering that these texts were private, utilitarian resources for a household, which is a difficult concept to grasp in our present age of globalized information. Measurements and yields are rarely enumerated, and many steps feel like arcane mnemonics rather than instructions for total outsiders (Pennell & Dimeo, 7). This provides strong evidence of private understandings between authors, since the missing steps indicate the possibility of extratextual communication within the Fairfax-Spencer family.

Prior to written systems of knowledge, wisdom in medicine was carefully preserved in oral tradition & passed down through communities, eventually being recorded by women in these recipe books. Starting in the 1800s, these methods would begin to be appropriated by male doctors who neglected to acknowledge the generations of women who compiled the research (Wear, 62). Thanks to modern analysis, we can properly honor these important innovators of practical science.

The Fairfax-Spencer Recipe Book is a valuable tool to researchers who seek to redefine preconceived notions of women’s authority and communal knowledge building, especially in contrast to patriarchal views of scholarship. Knowledge was not simply born from the minds of educated men who had access to means of publishing – it also came from hard work and dedicated practices assembled and refined by a community of women over generations.

Written by Aven Grote (2025)

Bibliography

Kowalchuk, K. (Ed.). (2017). Historical Introduction. In Preserving on Paper: Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen’s Receipt Books (pp. 3–55). University of Toronto Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctv1n3592n.5

Laroche, R., & Ziegler, G. (2011). Beyond Home Remedy: Women, Medicine, and Science. Folger Shakespeare Library. https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Beyond_Home_Remedy:_Women,_Medicine,_and_Science

Pennell, S., & Dimeo, M. (2013). Introduction. In M. DiMeo & S. Pennell (Eds.), Reading and writing recipe books, 1550–1800 (pp. 1–22). Manchester University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv5npjfw.7

Wear, A. (2000). Knowledge and practice in english medicine, 1550-1680. Cambridge University Press.