The Law School Battle: Trial and Triumph

On November 14, 1973, the George Mason University Board of Visitors agreed that Rector John C. Wood would send a letter of intent regarding the creation of a law school to the State Council of Higher Education in Virginia (SCHEV) in Richmond. A feasibility study that was already underway would be continued, and an advisory committee of citizens would be established to present a report on their findings to the Board as soon as possible. [1] The next day the letter was sent and what would prove to be a long, hard battle was underway.

George Mason became an independent university in the spring of the previous year and President Lorin A. Thompson began drafting plans for expansion almost immediately. John T. “Til” Hazel, an attorney, real estate developer, and a driving influence behind Mason’s acquisition of the Law School, had served the University in a variety of ways. He was a member of Mason’s Advisory Board, a member of the first Board of Visitors (later the Rector), and as both member and chair of the Board of Trustees of the George Mason University Foundation, which he had helped to establish. [2] Hazel believed that George Mason would need a law school in order to become recognized as a world-class university: “It would give professional status to the University and raise it above the community college status it otherwise always would have… [George Mason] needed a professional school, and the law school was the doable way to achieve that because it was not capital intensive. [3] Mason desired the support of the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) and needed the approval of the General Assembly before it could proceed. [4] While Rector John Wood and the Board of Visitors petitioned SCHEV, Hazel began a five-year lobbying effort in 1973 to request the General Assembly’s support, but his efforts bore no fruit. [5]

The Board of Visitors’ 1973 letter to the State Council was not received warmly. Dr. Daniel Martin, the Director of SCHEV, replied to Wood’s letter on December 21, 1973, emphatically stating: “…It is the judgment of the State Council on Higher Education that an additional law school is not needed in the Commonwealth in the foreseeable future.” [6] If anything, the Board of Visitors’ resolve was strengthened by this rejection. The University and Board of Visitors formed a law school advisory committee. It was chaired by James H. Simmonds, former president of the Virginia State Bar Association, and comprised twenty-two prominent attorneys and judges from Northern Virginia. It was tasked with compiling a report on the need for a law school in Northern Virginia. Dr. Lorin A. Thompson, who had retired the previous year as the first president of George Mason University, along with Michael Cardozo, former executive director of the Association of American Law Schools, also contributed. [7] The committee’s final report expressed its determination:

The establishment of a law school at George Mason University would be a step toward the development of a strong and diversified institution in accordance with the broad general goals of the Master Plan adopted and approved in 1968. In 1965 George Mason was recommended to become a regional university for Northern Virginia in the State Plan for the Development of Higher Education in Virginia...The bare fact that over 800 Northern Virginians are now forced, because of lack of facilities, to attend District of Columbia law schools, paying more than 3 times the tuition of the two state law schools, not only establishes a conclusive case of need, but speaks loudly as to the gross inequity of treatment of a large body of Virginia citizens. [8]

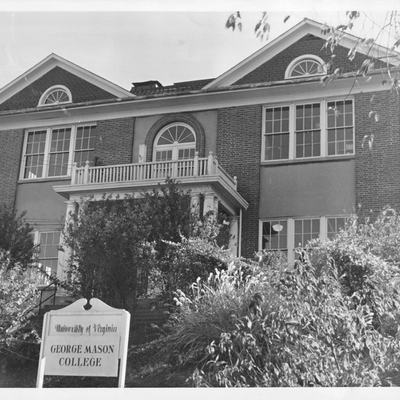

Undeterred by the previous dismissal, the Board of Visitors formally requested permission from SCHEV to establish a law school on September 26, 1974. [9] The Law School Advisory Committee held that “…The establishment of a law school at George Mason University represents an educational bargain for the Commonwealth of Virginia. With no capital outlay requirement and a small operating cost, the state can fulfill an obligation to its citizens and at the same time relieve the growth pressures on other institutions.” [10] The Board believed this proposal made a great deal of sense, considering the law schools at the University of Virginia and William and Mary were unable to serve hundreds of qualified students because of a lack of space. [11] They planned to house the law school at George Mason’s North Campus (the former Fairfax High School acquired by George Mason in 1971), so no construction costs would result.

Wood hoped that the law school would be approved by SCHEV so that it might receive the General Assembly’s backing during its brief 1975 session, in which case funds could be allotted for the University’s 1976 – 1978 budget. The Advisory Committee projected enrollment of 300 – 400 students in its first year; Virginia students would pay $1000 per year, and out-of-state students, $2100 per year. [12]

Some legislators, like Edward Holland, a state senator from Arlington, believed the Committee’s report “made an excellent case for the law school, pointing [out] the problem, the need and the feasibility for establishing the School within current budgetary limitations,” though he cautioned that the economic downturn during that time might present a roadblock to the proposal’s ratification in the General Assembly. [13]

In November 1974, the Board of Visitors received disheartening (and indeed hurtful) news. SCHEV had produced its own report about the feasibility of a law school at George Mason, and its desire to prevent the establishment of one was quite clear. George Mason, it maintained, was a “regional” university, independent for only two years, and as such, it “must be regarded as a developing institution with a promising future but one which has yet to establish either a reputation for excellence or the facilities required to achieve excellence.” [14] The report cited graduate programs that were not yet “fully productive,” a “markedly inadequate library,” lack of development, and the need for “considerable expenditures and commitment” among some of its concerns. It also relayed the expectation of Millard Ruud, Executive Director of the Association of American Law Schools, that “it [is] essential for a new law school to be competitive with the middle range, or average, law schools in the United States…there is simply no need or justification to start a new law school at any lower level.” [15] Seemingly associating George Mason with “lower level” institutions, the report attempted to console the Board of Visitors by offering: “[i]t is, in fact, more essential that a law school be part of a major university than it is that a major university have a law school.” The letter concluded by noting that the Council staff felt that George Mason was not the proper place at which to establish a law school, “even if one were needed in Virginia…It is clear from its [George Mason’s] own study that [the] university cannot, at this time, aspire to such excellence.” [16] Not surprisingly, the Board of Visitors’ request was struck down in the January 1975 General Assembly, as well.

The issue was becoming of increasing interest to the general populace throughout the state, and tensions were growing. An editorial entitled “Enough Law Schools” in the Richmond Times-Dispatch on January 24, 1975, called the State’s veto of a George Mason Law School “highly encouraging,” citing the evidence collected by the SCHEV report, the lack of jobs for lawyers, and the expansion plans in place at Virginia’s four law schools (the University of Virginia, William and Mary, Washington and Lee, and the University of Richmond). The author of the editorial C.L. Sulzberger, acknowledged that “Northern Virginians may regard their populous realm in the shadows of the District of Columbia as a region that merits its ‘own’ law school. But any law school worthy of the name is much more than a ‘community’ college; it is at least a statewide resource, and at best one of national attraction.” [17]

C. Harrison Mann, Jr., who was a major contributor in the fight for the law school, responded with his own commentary: “I was somewhat saddened, though not especially surprised, by your January 24 editorial, ‘Enough Law Schools’. I had hoped you had outgrown your parochial (‘to hell with them’) reaction to the needs of Northern Virginia.” He reiterated the number of Northern Virginians forced to pay thousands more to go to law school in Washington, D.C., and again pointed out that the existing Virginia law schools simply could not accommodate enough people: “‘That’s tough’ seems to be the attitude of the Richmond Times-Dispatch and the State Council of Higher Education…Obviously you couldn’t care less about the gross inequity of treatment of a large body of Virginia citizens.” [18]

Still resolute, the Board of Visitors made another formal request in 1976, but this also to no avail. [19] In a letter to the Honorable W. Roy Smith before the decision was made, Mann wrote:

I was asked …to make a presentation for the George Mason Law School, which is needed as badly as the dormitories aren’t [he did not at all support the construction of student dormitories on campus]...The object, as you know, was to get a reconsideration of last year’s decision, which I am afraid reflected some University of Virginia and William and Mary staff lobbying. Why the devil these two law schools should want to gig this proposal I don’t know since they aren’t admitting but one-third of the Virginia applicants, leaving the rest to scramble the best they can. Of course, they could admit more Virginians—but just try to get them to forget their Ivy League delusions. We have a tremendous professorial potential here in the large number of retireds and members of the bar who are highly desirous of teaching part-time. Admittedly, the professors’ union takes a dim view of this, much preferring to take theoretical, untrained teachers rather than the real world types. These ivory tower boys have considerable impact and influence on their counterpart types in the Council’s staff. I call your attention to the fact that there are also those who like to play God and contend that since nationwide we are over-producing lawyers, Joe Doaks should not be given his opportunity to get a legal education and try his hand at it if he wants. [20]

While Mann lamented the decision, it was praised by another editorial in the Richmond Times-Dispatch: “In restating its opposition to the establishment of a law school at George Mason University in Fairfax County, the State Council of Higher Education made exactly the right decision. It would be an egregiously irresponsible act for the General Assembly to override that decision.” The author expressed concern about spending during a period when funds for local schools and state colleges had been reduced and believed that the state already produced enough lawyers, continuing: “There is neither need nor money for such a facility. Until both materialize, George Mason’s proposal should be filed and forgotten.” [21] Following the two failed attempts and the wishes that the proposal be “filed and forgotten”, individuals within the George Mason community were beginning to feel as though their institution was not being treated as a “real university.” Former president of George Mason University, Dr. George W. Johnson, would later say, “[a] law school was the mark of a real university. For that reason, if not for others, it was fiercely resisted [by the state educational system].” [22] The two sides were pitted almost bitterly against each other—and George Mason was losing.

The winds of change would sweep through Northern Virginia later that year. The International School of Law (ISL) in Arlington was experiencing difficulties gaining accreditation and faced imminent closure. Realizing that a merger between the two schools would be mutually beneficial, Til Hazel and ISL dean, Ralph Norvell, met and agreed to work together for the mutual benefit of both parties. After meeting and entering into negotiations, the George Mason Foundation purchased the ISL property in Arlington’s Virginia Square neighborhood for $3.2 million in November 1978, one month before ISL’s lease was set to expire. The Foundation, a non-profit corporation established to supply the university with funds beyond that which it receives from the state, initially intended to lease the former Kann’s Department Store building, to prospective businesses to raise money for a new law school. [23] Following this relatively bold move, SCHEV issued another report to the General Assembly strongly recommending that the merger not be approved. [24] Things looked bleak for George Mason, as it faced a third rejection. The situation was even bleaker for ISL students, whose degrees would mean nothing without the merger because their school was not accredited. On November 7, 1978, Dean Norvell sent a message to the students and faculty of the ISL:

“I regret that I must confirm what most of you already know. [SCHEV] has acted unfavorably as to the authorization of a law school at George Mason University with the obvious consequence as to merger….There is no ambiguity as to the unfavorable nature of the Council’s action in terms of plans George Mason has been proceeding upon.” [25]

The next day, he added that the Board of Visitors and administration at George Mason were not prepared to back down but that “the responsible officials at GMU do not consider the matter resolved and have pledged to do all that is within their power to see the matter through to a successful conclusion.”

As preparation for the 1979 General Assembly Session began, Norvell commended his students for their poise and composure during such an uncertain period. [26] Dean Norvell’s students were more than just simply poised and composed. They became energized, and in the end they would play a crucial role in influencing the General Assembly’s final decision. In February 1979 several ISL students traveled to Richmond to personally lobby the General Assembly on behalf of the merger. Til Hazel also drove to Richmond to appeal to the legislature. Time was of the essence, because the Assembly is only in session for thirty days during odd-numbered years. “I was down there lobbying every way I knew how, but the real lobbyists, the effective ones, were the law students,” Hazel said. “They went down there and talked quietly and behaved and got the job done. The legislators saw they weren’t a bunch of student radicals, but were serious people who wanted a good law school.” [27] Legislators noted the power of their presence; one found them the “most positive effort of the merger campaign,” and many legislators would vote against SCHEV’s opposition this time because of the passion and eloquence of the ISL students. [28]

While the arguments both for and against the establishment of a George Mason Law School were essentially the same as they had been in the previous hearings, the stakes were much higher this time. Til Hazel noted that 1979’s request was distinct from the earlier petitions because it was “a once in a lifetime chance.” [29] George Mason could move into an existing facility with a large library, so there would be few start-up costs. Proponents of the merger continued to point out that Northern Virginians were in need of access to an institution offering legal education. Despite SCHEV’s advice, the State Senate and House of Delegates both passed Senate Bill 607 (on February 5 and 7, respectively) by large margins, to the surprise and delight of the George Mason community. [30] Vice President of Academic Affairs, Robert Krug, remarked that it was highly unusual for the General Assembly to vote against SCHEV’s recommendations. Marshall Coleman, Attorney General, noted, “I recognize that the Council of Higher Education has different views, but the Council’s function is advisory.” [31]

With the General Assembly’s passing of the bill, ISL merged with George Mason to form the George Mason University School of Law. The former ISL students received accredited degrees during the spring of 1979 and were able to take the bar exam. George Mason finally had a law school and the prestige that came with it. Harriet Bradley, a former Fairfax County supervisor and member of George Mason’s Board of Visitors, later noted that Til Hazel and George Johnson (along with the help of many others) “accomplished the seemingly impossible. [The acquisition of the law school is] a remarkable story.” [32] After losing several tough battles, George Mason University had finally won the war.

Browse items related to George Mason University School of Law