Before We Became Part of the Mason Family: The Story of the International School of Law

Vietnam veteran and recent graduate of University of Virginia School of Law, Daniel D. Smith and his wife were on their way to the Brabner-Smith farm one day during the summer of 1972. Smith was a United States Marine officer stationed at Quantico and was looking into going into private practice after being discharged from the service. While Smith’s career was just starting, John Brabner-Smith’s was winding down. Since receiving his law degree in 1927, Brabner-Smith had a long and distinguished career which included working to bring down Al Capone and teaching law at Northwestern Law School. [1] Mrs. Brabner-Smith and Mrs. Smith were already friends. They thought their husbands, who both shared similar interests, should meet. The two men hit it off almost immediately, and Brabner-Smith went on to reveal his plans for the next stage in his career to Daniel Smith. [2]

Brabner-Smith planned to start a law school. He told Daniel Smith that the outlying areas in Northern Virginia needed an exclusive school to call their own. The great demand for a legal education meant that hundreds of unsuccessful law school applicants were left without a seat at any institution each year. These applicants could potentially constitute the student body of a brand new law school. Brabner-Smith insisted that his institution would be different from la schools operating at that time: it would provide students with a strong foundation in the origins of law, particularly its Judeo-Christian roots. The study of morality and ethics would be an integral part of the curriculum of Brabner-Smith’s school. Several weeks after their initial meeting he offered Daniel Smith a spot on the small committee he founded to organize the law school. At first, Smith declined, hoping to continue with his plan of opening a private practice. After reconsidering the idea, Smith accepted the offer in August 1972 to help organize a new law school. [3]

In order for a law school to succeed it must have students willing to attend it. Daniel Smith and another school organizer, recently retired labor law judge George Powell, traveled to the admissions offices of several area law schools. While the offices could not legally release any confidential information, they did give Smith and Powell the names and contact information of approximately six hundred applicants. Using a mimeograph machine, Smith drafted letters to be sent to them, gauging their interest in attending a brand new law school. Smith also found a home for the school in a classroom at the Federal Bar Building on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington D.C. A deal was struck to allow the law school to rent the classroom space when not being used by law review courses. Brabner-Smith formally christened the law school the International School of Law (ISL). The name was chosen because Brabner-Smith intended for the school to focus on international law, although this idea never quite fully developed. [4]

The International School of Law began meeting with prospective students in the rented classroom in September of 1972. It was decided that veterans entering the school would not be charged tuition. Usually, the federal government compensated veterans for tuition at approved schools. However, the ISL was not accredited at the time and thus, not approved. Veterans made up about one-third of the inaugural class, and despite considerations to the contrary, the ISL would never charge veterans for tuition during the entirety of its existence. [5]

Obtaining accreditation by the American Bar Association (ABA) was the first major problem the ISL faced in the beginning. Such accreditation is necessary in order for a law school’s students to be permitted to take the Bar Exam in the United States. While it is not uncommon for a school to be rejected for approval the first or even second time an accreditation review is requested, school administrators needed a contingency plan in case the school was not accredited by the time the first class graduated. Administrators discovered ways in which a student could still sit for the Bar Exam in certain states without graduating from an ABA-accredited school. The ISL did receive accreditation by the Virginia Bar Association about 3 years after its founding. This permitted ISL students to sit at least for the Virginia Bar Exam.

The first ISL class was comprised of 32 students, and all faculty members were hired on a part-time basis. Brabner-Smith was appointed Dean of the Law School and Daniel Smith was named Administrative Dean. As Administrative Dean, Smith’s job was to hire faculty, set up classes, and maintain facilities. Both Brabner-Smith and Smith taught classes, and in keeping with law school tradition, the ISL did not permit first-year students to take classes outside the established curriculum.

During the second year of its existence, the ISL moved its operations to the home of former United States Chief Justice Douglas White on Rhode Island Avenue. [6] It was during this time that the ISL finally began to grow in size and stature: the school now had extracurricular activities such as a Student Bar Association, a law review journal, and a moot court. However, despite these achievements, it was turned down for accreditation by the ABA. The ABA told the ISL that it needed a larger library, more updated facilities, and a full-time faculty. Students and faculty pitched in to renovate their existing building, although a lack of money made it very difficult to expand the library or hire full-time faculty. The ISL began to participate in a network with other law libraries in which books and journals were traded. Daniel Smith supervised the law library until the ISL garnered enough money to hire a law librarian. When Brabner-Smith left the school in 1975, Smith served as Acting Dean of the ISL for a few months. [7]

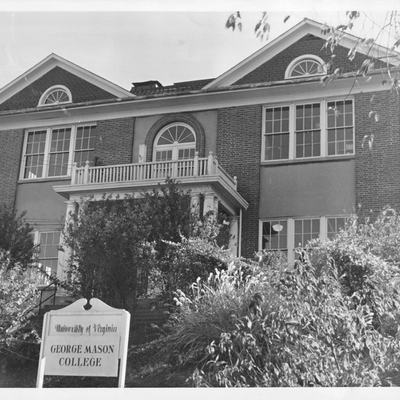

In September of 1975, Ralph Newton Norvell, a respected legal scholar, was appointed Dean of the ISL. Norvell believed that the ISL needed a bigger facility, so the institution purchased a building in Arlington which had recently housed Kahn’s Department Store. [8]There was talk of a Metrorail line running through Arlington, and Norvell thought that the future Metro line would make the ISL more attractive, thereby increasing admissions. However, despite all the improvements, ISL still could not achieve accreditation. The school administrators knew that the only way to achieve accreditation would be to affiliate the ISL with a major university.

The idea of a merger of the ISL with George Mason University first emerged in1976. The Honorable Charles S. Russell, a judge for the Seventeenth Judicial Circuit and later, the Supreme Court of Virginia, was a close associate of ISL dean, Ralph Norvell. Russell became aware that the George Mason University Board of Visitors was interested in adding a law school to their relatively new university. Aware that both institutions were looking for possible partnerships, Russell set up a meeting between Norvell and the Rector of Mason’s Board of Visitors, John “Till” Hazel. The meeting took place in Arlington at an eatery across the street from the ISL campus. Hazel and Norvell agreed that a merger would be highly beneficial for both the ISL and George Mason. It would be particularly appealing to the ISL as the ABA was in the process of instituting a new regulation requiring law schools to be affiliated with an existing institution of higher education in order to receive accreditation. Mason’s Board of Visitors thought that acquiring an existing law school would probably be more attractive to the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) and the General Assembly than establishing a brand new, and most likely, more expensive school. The two men had lunch, shook hands, and agreed to work together and do whatever was necessary to convince SCHEV to approve the merger. [9]

Browse items related to the International School of Law.

[7] Daniel Smith Oral History 2009