McCarthyism and Red Hysteria

On February 9, 1950 a lesser-known U.S. senator from Wisconsin by the name of Joseph McCarthy made a striking statement in a speech at a women’s event in Wheeling, West Virginia. He told the Lincoln Day audience that he held in his hand a list of 205 known communists who worked in the State Department. In subsequent speeches and press conferences the number shrunk to 57 and then 4. When asked by reporters to share the list with them, he said that he could not because had left it in his other suit. He later claimed the list had been either lost or stolen. While the senator had not won over the press with his unproven and ever-changing story, he struck a chord with many Americans who were concerned by the “loss” of China and other countries to Communism and the seeming ineptitude of United States government officials, such as President Harry S. Truman and Secretary of State George C. Marshall, and military leaders to prevent the spread of communism.

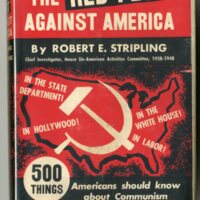

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began in 1938 with the mission to investigate anyone or any organization that might sympathize with fascism or communism. In the late 1940s the Hollywood Ten, a group of motion-picture industry figures appeared before HUAC, and were sentenced to prison for not answering whether they were involved with communist causes. These individuals were later blacklisted by major Hollywood studios. By 1950 there was no shortage of those who argued that communists had infiltrated nearly every facet of American life. That year the investigations spread from the House to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, based on McCarthy’s charges about State Department employees.

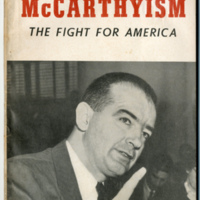

Over a four-year period Senator McCarthy, taking advantage of the political climate in the country, made a name for himself by accusing employees of government institutions, colleges and universities, and members of the entertainment industry of being communist agents bent on destroying the United States from within. In a series of public hearings before the Senate committee, McCarthy made these claims against individuals with very little or no evidence at all. Since the public sentiment against Communism ran high at that time, and it seemed as if McCarthy might have been on to something, many politicians, from both parties were initially reluctant to challenge him. At the height of his popularity in 1952, McCarthy published a self-promoting book entitled: McCarthyism: The Fight for America.

McCarthy’s downfall began in 1953 when he launched an investigation into widespread communist infiltration in the U.S. Army as chair of the Senate Committee on Government Operations. After numerous days of hearings and multiple accusations, McCarthy could only prove that an army dentist who had been a member of a left-wing labor group was promoted to the rank of major. He was ridiculed in the press for only discovering one “pink dentist” in this investigation. The next year, the U.S. Army investigated McCarthy and an associate (Roy Cohn) for pressuring the Army to give special privileges to a recently-drafted soldier they knew. The investigation provided no evidence to that effect but the hearings, which were broadcast gavel-to-gavel for over a month to a large television audience, showed McCarthy to be cruel, dishonest, and vindictive in his handling of witnesses. In a fiery interchange with McCarthy, the Army’s legal representative Joseph Welch famously asked if “had no sense of decency” left. The chamber erupted in applause, publicly humiliating McCarthy. Six months later the Senate voted to officially censure him for his behavior, and in 1957 McCarthy died of liver failure.

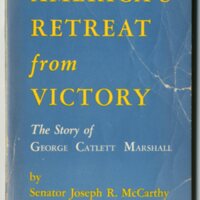

Individuals like Joseph McCarthy often played on the public’s fear of the spread of Communism to influence public opinion, advance a personal agenda, or, sometimes, to sell books.