The Creation of the Office of University Life: Enriching the Mason Experience

Beginning in the late 1990s George Mason University has been transformed from what many considered a strictly “commuter college” offering relatively little beyond an education to a residential institution with a vibrant campus life and many activities and services available to students, faculty, and staff. The Office of University Life, a unit that comprises nearly thirty academic, cultural, and social entities, is one of the largest administrative units at George Mason University, connecting students, faculty, and staff to a wide variety of programs and resources essential to their successful integration into the university. University Life is relatively young, having been instituted only shortly after the installation of Dr. Alan G. Merten as President in 1996. [1]

Previously, university groups that catered to student life had been under the direction of the former Student Affairs Office and had reported to the Senior Vice President of the university, Dr. Maurice Scherrens. Upon arriving at Mason, Dr. Merten found this indirect reporting structure unsatisfactory for such an important function. He expanded the scope and clout of the Student Affairs Office by renaming the division “University Life”, appointed a vice president to head it, and included it in his weekly roundtable discussions with key university groups. [2]

Dr.Karen Rosenblum, a sociology professor at Mason and the first director of its Women’s Studies program, was appointed the first Vice President of University Life in 1997. Rosenblum later noted that President Merten’s choosing to fill the position with a tenure-track faculty member (particularly a woman), rather than someone with a Student Affairs background, was almost “unprecedented”—“it put Dr. Merten on the map for that kind of thing within the university and in the country.” [3] Merten had hoped to strengthen student and faculty ties to the administration by appointing a faculty member to direct the office, and Dr. Rosenblum felt that her connection with the faculty did provide a vehicle for them to become more involved. [4] The increased visibility of the office and its upgraded position during budget decisions were important changes, and with a new name and a bigger budget came new opportunities to craft initiatives aimed at increasing spirit and the sense of community on campus. In her 1998 End-of-the-Year Address to University Life staff, Dr. Rosenblum stressed that building community would require “building tradition; personalizing the campus; making visible a George Mason identity; enticing faculty out of the classroom and into student interaction; and creating a climate in which students, faculty, and staff feel recognized and valued.” [5]

While “University Life” as a division was conceived by President Merten, the concept was also on the mind of Dr. George Johnson, his predecessor. In the early 1990s Johnson commissioned a University Life Project Team to assess the needs and strengths of George Mason’s growing campus community, particularly its “learning communities”. However, the interim report produced by the team in May 1991 focused largely on faculty needs and administrative policies, rather than on student-related issues, a choice stated explicitly by the committee: “We did not give serious attention to students, student cultures and motivation, student involvement in university decision-making and such matters.”[6]The report reflected faculty, staff, and administrators’ suggestions for the university’s improvement; they believed that “addressing [student concerns] effectively depend[ed] on resolving more basic issues concerning the institution and its faculty”, and so became the team’s “top priority”. [7] However, a Student Services Transition Team was constituted by President Johnson in December 1994 to “assess existing student service in terms of current functions, their current linkages with other academic and support services, and possible realignments” in order to determine “the extent to which they reinforce learning”. [8] This team, which suggested organizing student services into five “clusters”—for example, “Student Development” and “Intercultural,” among others— paved the way for the structural foundation of University Life, which reorganized itself into three clusters (Health and Wellness, Campus Life, and Academic, Career, Counseling, and Educational Services) in 1998. [9]

University Life’s initial Mission Statement was drafted in the spring of 1998. It stated: “University Life provides academic, career, social, emotional, and health services that are integral to students’ educational success and to the fostering of a unified community”. [10] Dr. Rosenblum believed that it was evident that the offices encompassed by University Life needed a more focused, unified vision, as surveys taken by graduating seniors in 1997 indicated a general dissatisfaction both with their sense of belonging on campus and with overall “campus life”. [11] By charging the multiple offices within the University Life division to consider their programs in terms of their “impact,” Rosenblum hoped that the multiple offices would become more “open to new ways of working—ways not based on the fact that we have always done this, or done this much, or done it this way, but instead operate from what we can determine to be the outcome of our work”. [12] In order to determine how University Life could continue to improve the campus experience for students, Dr. Rosenblum hosted the university’s first “Listening Days” in April 1997. [13] She and other faculty and administrators took comments, complaints, and suggestions from students, faculty, and staff. Both a lack of faculty-student interaction and the perception of a lack of community were frequently raised criticisms by students, and these were two issues that Rosenblum worked to address through University Life’s various offices and resources. [14] Faculty members were invited to participate in Welcome Week events for Freshmen, and the advising process was addressed. [15] A committee was established in the summer of 1999 to design and implement a greater number and variety of weekend programs. [16]

Dr. Rosenblum felt that her efforts to promote diversity—“the university’s calling card”—were one of her greatest contributions to University Life. [17] Rosenblum believed that “[W]e are on a good trajectory on a number of things [including] creating an environment where we have a lot of student diversity, and that diversity is a positive experience for our students. That trajectory we want to maintain”. [18] She had experience promoting diversity before her time in University Life; shortly before her appointment as its Vice President, Rosenblum had helped to organize the “Changing World of Work” series, which included lectures, seminars, and workshops that explored the roles of women and minorities in the workforce. [19] The event was one that represented a goal of Dr. Merten’s for the university: “We want to provide an ultimate tolerance for diverse opinions at this institution.” [20]

Dr. Rosenblum explained that an influx of immigrant and refugee students from areas like Korea, India, and the Middle East had a significant influence on the student body and made the university “much more appealing to students who live in areas that don’t have this diversity.” [21] In an effort to increase awareness of diversity, she promoted Mason’s partnership with the National Coalition Building Institute (NCBI). In a letter to members of the President’s Council, Rosenblum explained that NCBI teaches “prejudice reduction and conflict resolution models that have been key to reducing inter-group conflict at many colleges in universities” and that its “programs offer a systematic approach to welcoming diversity and addressing controversial issues both in and outside of the classroom”. [22] She encouraged faculty and staff to attend workshops and to extend the invitation to their co-workers, as well. In the early 2000s, a committee tasked by Dr. Merten to review the function of the University Equity Office agreed that the office should “broaden its mission to include the issue of diversity.” [23] It noted that “University Life has done a much better job with students than we have for employees on the issues of diversity. Graduating seniors on our annual survey routinely report that GMU’s diversity is one of the strengths of their experience at Mason;” that observation was likely due to Rosenblum’s initiatives. [24]

Dr. Rosenblum noted that one of the biggest changes brought on by the advent of University Life was in regard to housing. In 1995, George Mason “became one of the first universities in America to privatize campus housing for students.” [25] The university had “neither the staff, nor the expertise, nor the money” to direct housing on its own at that time. But students soon found the quality of the administration and upkeep of housing by outside contractors unsatisfactory. Rosenblum felt that housing’s later coming under the control of the university again, this time as part of University Life, has resulted in a dramatic positive change. [26] Dr. Rosenblumadded that she did not necessarily feel that a great deal of change in regard to spirit on campus occurred during her tenure (1997-2004). While the student body grew in size and became more diverse, she felt that many of the traditional attitudes toward campus—that it was a place to get a degree in order to prepare for a career, that it was a place to take classes during the day before returning home—remained. She cautioned against this mindset: “The more engaged a student is with a full [campus] life, the more they get out of their classes and the more they develop as human beings. So students should not just go home after class because then they are not getting a college education; they are taking classes.” [27] Dr. Rosenblum left her position as the head of University Life in 2004 to return to the classroom. While she did not believe a dramatic shift occurred in campus culture during her time as Vice President for University Life, many students felt that her work was highly influential; the Editor-in-Chief of Broadside said in a special letter that “Her dedication and passion toward shaping the minds of tomorrow are unparalleled.” [28]

Dr. Sandra Hubler Scherrens became the second Vice President of University Life that same year. Though she had been working in California in a similar capacity for a number of years, Dr. Scherrens was drawn to George Mason because of the beauty of the campus and the people she met, particularly President Merten. His acknowledgment of the fundamental importance of students was one that inspired her, as he believed that “the co-curricular experience is just as important as the academic experience; they go hand-in-hand.” [29] She was attracted by George Mason’s vision for University Life—it was the only university in the country to give the division that title rather than “Student Affairs”—because it was dedicated to “integrat[ing] the whole university experience into student life” by focusing on faculty and staff experiences, as well, and how they influence student experience. [30] She continued to pursue Rosenblum’s mission of promoting a more engaged and spirited university community, a mindset exemplified through the introduction of University Life’s new Vision Statement in 2007: “University Life creates purposeful learning environments, experiences, and opportunities that energize ALL students to broaden their capacity for academic success and personal growth. Through innovative programs, partnerships, and direct services, students discover their unique talents, passions, and place in the world.” [31] Under her leadership, University Life also introduced its Core Values in 2007: Foster Student Success, Live and Act with Integrity, Embrace Our Differences, Catch the Mason Spirit, Show You Care, Dream Big, Celebrate Achievements, Pursue Lifelong Learning, and Lead by Example. [32]

Dr. Scherrens recognized the symbiotic relationship that existed between the student body and University Life; the ever-growing student body necessitated the programming of University Life, and the success of University Life programs and services continued to draw more students to campus because of the appeal of its vibrant community. That community has been shaped by events and programs like Greek Week, student lunches with Vice Presidents, and the on-campus student employment program, as well as the construction and/or renovation of student centers—Student Union Building I and the HUB—and dormitories, all of which have had “dramatic [effects] in terms of student engagement.” [33] Scherrens noted that the residential community grew fifty percent during her time as Vice President of University Life and was designated a “primarily residential campus” in 2011 by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of teaching. [34] Like Rosenblum, Scherrens saw that the direction of housing was one of the biggest transitions during her time at Mason; the Office of Housing and Residence Life came under the management of University Life on January 1, 2010 after being outsourced, and a number of positive changes resulted. [35] Student retention increased, as did the size of Scherrens’ staff; when she came to Mason, approximately 100 staff members worked for University Life, and by spring 2012, around 600 did (including those in housing). [36] This change in residential life was not just about numbers, however; it represented a “culture shift,” as a greater number of resources became devoted to creating evening and weekend programming and new facilities: “This growth is very exciting, and it makes the mission of University Life more important than it has ever been.” [37] Scherrens said that when she came to George Mason, she often heard that there was “nothing to do” on campus. When she read an editorial in Broadside in 2011 that said, “[George Mason] feels like a real campus”, it was “the best thing [she] could possibly hear.” [38]

The increase in the number of residential students led to new programming also called University Life to examine other constituencies that it could better serve. Off-Campus Student Programs and Services was created to provide information and resources to a large commuter population, and Graduate Student Life was developed to ensure the integration of graduate students into the campus community. [39] New offices were also created to help students foster particular skill sets; when Scherrens came to campus, she did not feel as though there were opportunities for students to engage in leadership development, so the LEAD (Leadership Education and Development) Office was born just two years after her arrival. [40]

At the beginning of her time as Vice President of University Life, Dr. Rosenblum had seen unsettling “satisfaction” surveys in regard to feelings of community at George Mason. Dr. Scherrens initially faced those issues, as well, but over the course of her eight years as Vice President, National Student Engagement (NSE) surveys taken by students during their freshmen and senior years revealed that students’ sense of belonging had “increased dramatically.” [41] Scherrens credited University Life as a major contributor to helping students get involved and take pride in their university. Rosenblum’s “Listening Days” initiative revealed that many students had been dissatisfied with the lack of student-faculty interaction; one of Scherrens’ responses was to create the Faculty Fellows program in 2004 based on an initiative begun in 1999. [42] During a five-year period, forty faculty members were given stipends and release time to work with University Life in co-curricular areas like retention or “campus climate.” [43] University Life and faculty have a “great relationship”, Scherrens said—faculty “are eager to get involved and really do care about students.” [44] While formal assessments are a part of each office’s programming, Dr. Scherrens believes that University Life is effective because its staff interacts with students: “University Life is so good at relationships. We care, we ask, we go to student organization meetings; that’s really how we learn what their [students’] needs are and whether or not we’re meeting them.” [45]

Dr. Rosenblum believed that diversity was one of George Mason’s strengths, and Dr. Scherrens viewed it as a great asset, as well. University Life continued its partnership with the NCBI, collaborating with professors to provide diversity workshops in entry-level communications classes and becoming the headquarters for the Northern Virginia NCBI program. [46] The campus, which had been diverse when she came in 2004, continued to become even more diverse, and the success of University Life lay not only in recognizing that diversity but also in addressing issues associated with it: “What we continue to do better is to celebrate the diversity, to recognize where we are diverse. You want to bring everybody together to celebrate diversity, but you also need to make sure that individuals from distinct groups are getting the experience they want. [We have been] more deliberate about making sure we address the needs of our diversity.” [47] This philosophy was embodied in one of the Core Values introduced by University Life in 2007 in “Embrace our Differences.” [48]Cultivating an atmosphere of diversity is also part of the strategic plan of the university and is shared across the institution, from Admissions to university and student publications to the identity-based organizations of University Life and its Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Multicultural Education. [49]

Perhaps one of the biggest changes in the campus community came through an athletic event—something outside the scope of University Life. George Mason’s “Cinderella story” NCAA Final Four run in 2006 certainly played a major role in increasing “Patriot Pride”—Dr. Scherrens commented that the historic event was “unbelievable”, bringing about “a huge culture change” on-campus in terms of spirit. [50] Several University Life publications in subsequent years allude to that change, and in a letter to alumni in the fall of 2006, President Merten also addressed its importance: “Fresh off a year that brought us that magnificent march to the NCAA Final Four by our men’s basketball team, the Mason community is energized by the spotlight of international recognition for who we are and what we have accomplished as a university…Patriot Pride abounds.” [51] University Life capitalized upon that achievement:

For many years, the administrators within Mason worked to develop a plan that would make the university an attractive place for all students—preparing for any opportunity that would thrust Mason into the spotlight. With the proper foundation in place, thanks

in large part to the work of Dr. Morrie and Dr. Sandra Scherrens, Mason was primed to take advantage of their opening, when the men’s basketball team made its improbable run into the Final Four. Freshmen applications increased exponentially, transfer applications hit an all-time high and, most importantly, students were arriving at Mason because they wanted to be a part of something. [52]

When asked what she would tell a future Vice President of University Life, Dr. Scherrens responded: “People and relationships are key, and I think that’s what’s special about Mason. [They’re] the foundation of everything; with solid relationships, you can create and overcome anything.” [53]The transition to a new Vice President came more quickly than Scherrens anticipated, as her husband, Senior Vice President Dr. Maurice Scherrens, accepted a position as president of Newberry College in South Carolina in May 2013, and she decided to leave Mason with him. [54] Associate Vice President of University Life Rose Pascarell became Vice President in 2013 to oversee University Life’s Strategic Plan for 2014. [55]

University Life continues to provide the services that draw students to George Mason through its current initiatives and programs. Career Services offers resume review sessions; conducts an On-Campus Interviewing program; directs HireMason, a website that connects students and employers throughout the country and through which students can apply for internships and full-time positions posted on the site; and hosts job fairs and career panels with professionals in the defense and intelligence fields. [56] The LEAD (Leadership Education and Development Office), which was implemented by Dr. Sandra Scherrens, hosts leadership conferences and retreats; directs the Center for Leadership and Community Engagement (CLCE), which offers alternative spring break trips and a new Nonprofit Fellows Program through which select students can gain a Nonprofit Studies minor in a single semester of experiential learning; and began the Mason Gives Back blog during the 2012 – 2013 academic year, which allowed members of the Mason community (whether students, professors, or alumni) to post about new initiatives and service projects with which Mason students could become involved. [57] The Early Identification Program (EIP), which serves as Mason’s college preparatory program, celebrated twenty-five successful years in 2012 and has worked with over 1000 first-generation college students since their middle or junior high years to equip them “to become lifelong learners, leaders, and responsible global citizens.” [58]

Whether overseeing intramural sports programs, planning weekend programs, or helping students to prepare for life after college, the offices of University Life “continue to be the catalyst for keeping the university connected and engaged” on campus and in the global community. [59]

Browse items related to university life.

Life, Box 2; “University Life Innovations,” 2011, University Life, Box 11

Box 11

Life, Box 2

Scherrens, May 16, 2012

correspondence, June 2, 2013

correspondence, June 2, 2013

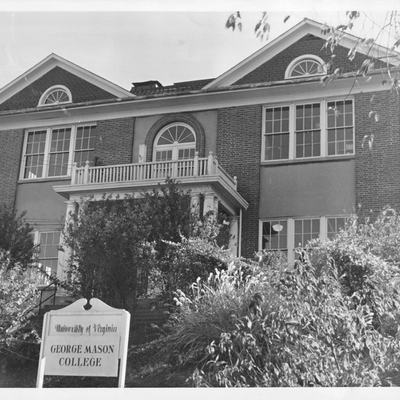

![R0120_B57F08_01[07-24-97].jpg R0120_B57F08_01[07-24-97].jpg](https://masonlibraries.gmu.edu/masonhistory/files/fullsize/6a0ae78dcb1f7ebc4c60a829bd58c952.jpg)