Student Unrest at Mason and The Gunston Ledger/Broadside

The late 1960s were a time of protest and unrest on college campuses across the country. George Mason, although its student body was mostly conservative and quite often characterized as apathetic, was no different. Friction between the few radicalized young people and the establishment was growing over U.S. policy in Vietnam. Students and some faculty would indeed take part in larger protests and demonstrations and would even instigate their own.

A key organizing agent during this period was the student press at Mason. The student newspaper, The Gunston Ledger, was begun in the fall of 1963 and served to inform students of news and events on the George Mason campus, first at Bailey’s Crossroads and later at Fairfax. Initially, The Ledger was a monthly publication. It tended to be more informational in substance and kept a low profile, reporting and opining on current campus items of interest, such as dances, sports, clubs, faculty, and students in a very measured and matter-of-fact style. It later moved to a weekly format and developed its own personality as the issues of the mid-1960s made their way into campus consciousness. Beginning in the fall of 1967, the staff of the Ledger became more political in their reporting on social issues such as the Vietnam War, poverty, racism, and academic freedom. The editorial opinion and news reporting of the Ledger (renamed Broadside in October 1969) leaned decidedly to the left. On at least two occasions during 1967-1970 the political tenor of reporting in the Ledger/Broadside, put the paper in a difficult position with the college administration and student government.

There were sporadic events dealing with social issues being talked about on the Mason campus in 1967. During that year The Human Be-In, which took place in Washington on April 14 was mocked by the Ledger, and its participants were treated as oddities. On April 28, activist George Lear spoke to about thirty students in the Lounge about the Vietnam War and pacifism. This story drew letters to the editor from both sides of the spectrum. By October 4 a Ledger editorial piece lobbied for the legalization of marijuana. Mason philosophy professor James M. Shea’s long letter of October 19th declaring his opposition to the draft, began the paper’s three-year fascination with his story.

One of the earliest protest events covered by the Gunston Ledger was the two-day march on the Pentagon on October 20 and 21 in 1967. This nationally-organized gathering drew an estimated seventy thousand participants. In the October 26 issue of the Ledger a first-hand account of the rally was provided by an unnamed Mason student who participated in the event. The story featured four photographs of the event, taken presumably by the writer. [1]

From this jump-off point the Ledger became increasingly political and appeared to place a much higher value on reporting and editorializing on social issues such as the Vietnam War, pacifism, and illegal drug use. Closer to home, the Ledger became a vocal critic of the administration and the Student Government (SG). Articles and political cartoons, particularly during 1969 and 1970 were often critical of Chancellor Thompson, Dean Krug, and their superiors in Charlottesville, often portraying Thompson and Krug as either puppets of president Edgar Shannon or as dictators lording over the Mason community. Throughout the end of the 1960s there would also be friction between the paper and the SG. This was a precarious situation for the Ledger, as the SG managed student-run activities and controlled the paper’s budget. The SG sometimes wished to keep the time, place, and subjects of certain meetings secret. However, the paper’s staff somehow was able to glean this information and print what they had learned in later issues to their dismay. The SG often took issue with the Ledger’s content, declaring that there was too much coverage of social issues and not enough of college events, sports, clubs, and academics. Twice during the late 1960s members of the SG attempted to reign in the Leger by threatening or actually cutting back needed funds for the paper.

Even though 1968 was a banner year for overt and sometimes violent protests, both at college campuses and elsewhere, the campus of George Mason College remained peaceful. In the wake of the Martin Luther King, Jr. assassination, the Ledger simply mourned “the passing of a friend.” A few low-key teach-ins took place on campus in April, but the campus was relatively quiet throughout the year. Perhaps this can be partially attributed to a University of Virginia policy of May 1968 designed to limit the size and scope of demonstrations on University grounds. Leaders of legitimate student groups were required to give ninety-six hours notice of planned protests. Picketing would not be allowed inside of buildings, and outside picketing should not disrupt the flow of traffic. Finally the location and numbers of participants had to have been agreed upon in advance. On May 7, Chancellor Thompson passed a typewritten document along to the Student Government and The Gunston Ledger to be distributed to the students. Dubbed the “Riot Kit” by the Ledger, it contained a form to be filled out by those planning on staging a protest.

During the first half of 1969, the Mason community probably came as close to holding a newsworthy demonstration as it ever would, as a student strike threatened in May. At issue in 1969 was academic freedom and the perception that the administration was attempting to stifle it. The fight against the Vietnam War itself temporarily took a backseat to the fight for the right of faculty members to speak out against the war and encourage students to follow suit. Several popular Mason professors would take center stage in this drama, while the Ledger helped to fan the flames of discontent. The Gunston Ledger itself would change its name to the more revolutionary-sounding Broadside in October claiming that the old name “no longer represents the things which we want it to stand for.” [2]

Two popular instructors, Larry Leftoff (Mathematics) and Ruth Flint (Biology) were dismissed by the University in December of 1968. It was suspected by students that they were let go because of their political beliefs and associations, although the University maintained that it was strictly because they had not fulfilled requirements for renewal. A third, an Asian history instructor named William Tsow, was let go for budgetary reasons, according to Chancellor Thompson. Former students of Tsow believed that his dismissal was brought on by his frank discussions regarding French and American involvement in Vietnam in the classroom. [3]

Undoubtedly, the subject of most of the discussion during this period was professor James M. Shea of the Philosophy Department. Shea refused to be inducted into the army in 1967 and had taken part in numerous demonstrations, including draft card burnings over the years. In 1968 he started the Free College of Northern Virginia, which offered free lectures focusing on modern social problems such as poverty, war, disease, and injustice. Free College field study trips included the March 14, 1969 picketing the Fairfax office of the draft board. While Shea remained at Mason until the fall semester of 1970, he was the subject of constant scrutiny by the administration and would only receive one-year contract renewals, instead of the customary three-years. A May 15, 1969 special edition of the Ledger detailed a planned student strike in support of Dr. Shea set for the next day, but the strike failed to materialize. [4]

One event that did materialize, however, was the October 15 Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam. As part of a larger international movement, this peaceful day of protest took place on the George Mason College campus and at other locations in Fairfax. Over 300 George Mason students participated in the events which included readings, speeches, and singing in the Lecture Hall and a procession to the local office of the Selective Service in downtown Fairfax. [5]

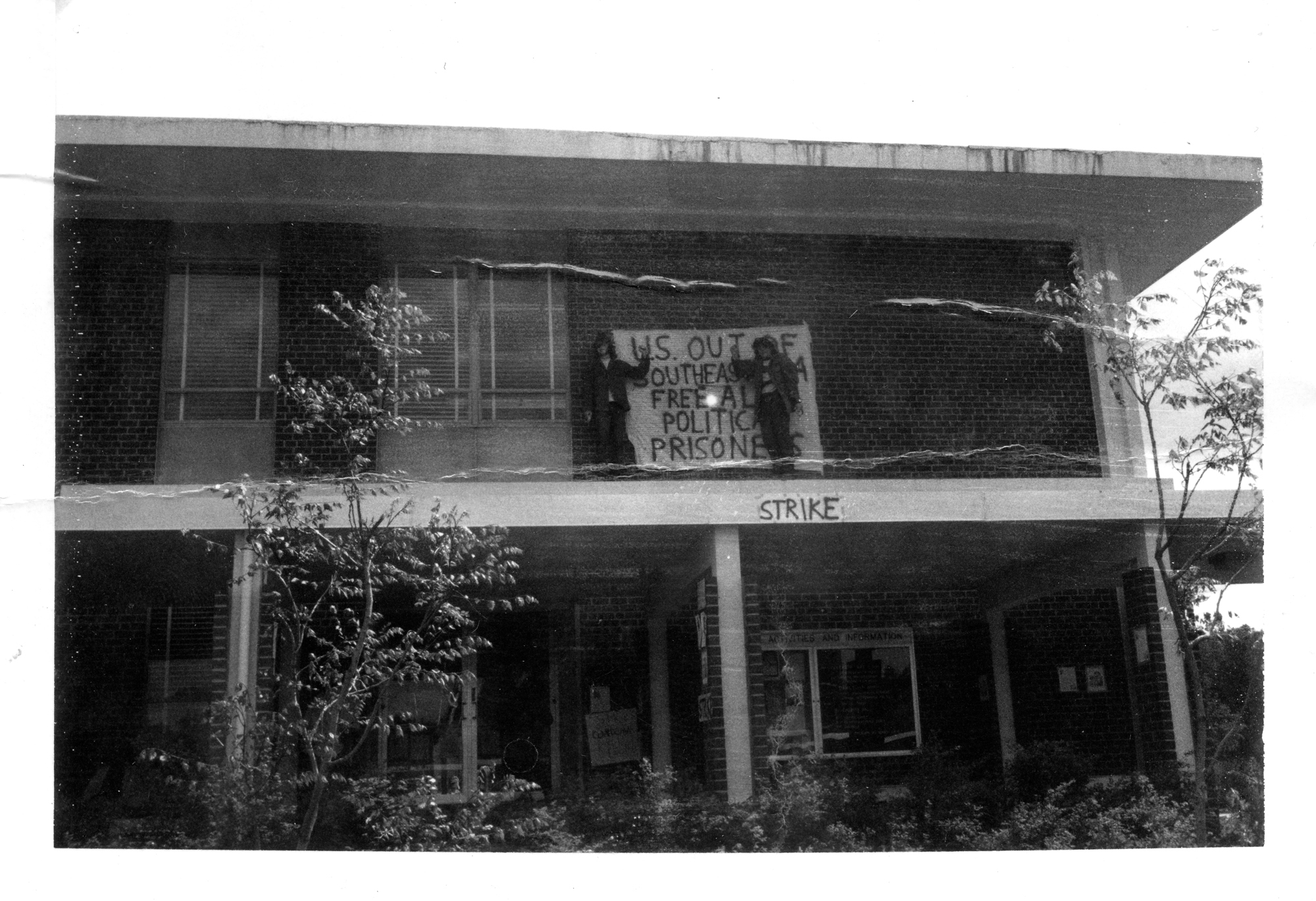

On May 4, 1970, at 12:25 PM Ohio National Guardsman opened fire on a group students protesting on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio, killing four of them. Two days later, several George Mason Students gathered in the quadrangle to listen to speech by an unidentified man, purportedly a student of Kent State. After hearing the speech, the Mason students went to the flagpole in front of the North Building and attempted to lower the flag to half-staff to honor those killed at Kent. Though some reports of this incident maintain that someone climbed the flag pole and others claim that the flag rope was cut, all seem to agree that the students demanded that the flag be lowered. Campus police arrived shortly as did Chancellor Thompson. Thompson, in an oral history interview conducted in 1983, recalled that he did not believe that he had the authority to lower a flag to half staff on his own. But, as tensions grew he asked that a small group of students join him in his office to talk the situation over. After a short meeting, Thompson agreed to lower the flag. He did so for an unspecified amount of time and offered a moment of silence. Satisfied with this gesture, the students dispersed. Looking back at the events of that day, Thompson felt that he had avoided a small riot. [6]

The flag pole incident in 1970 seems to have marked the beginning a slight lessening of the Broadside’s fixation with radicalism and activism on campus. The newspaper’s focus appeared to have shifted from that of mainly political action to a more balanced mixture of academics, sports, events on campus, and student life. Throughout the early 1970s the Broadside found more space to concentrate on Mason’s rapid enrollment growth, its forthcoming independence from the University of Virginia, campus expansion, and the beginning of the shift from a strictly commuter school to a partially residential university with the start of construction of student housing in 1976. Of course, the Broadside would never cease reporting or commenting on issues of academic freedom, social concern, or politics, as in the case of professor, Edmund “Fred” Millar in 1976. It would simply have to weigh those against other happenings on what was rapidly becoming a larger, busier campus.