-

Title

-

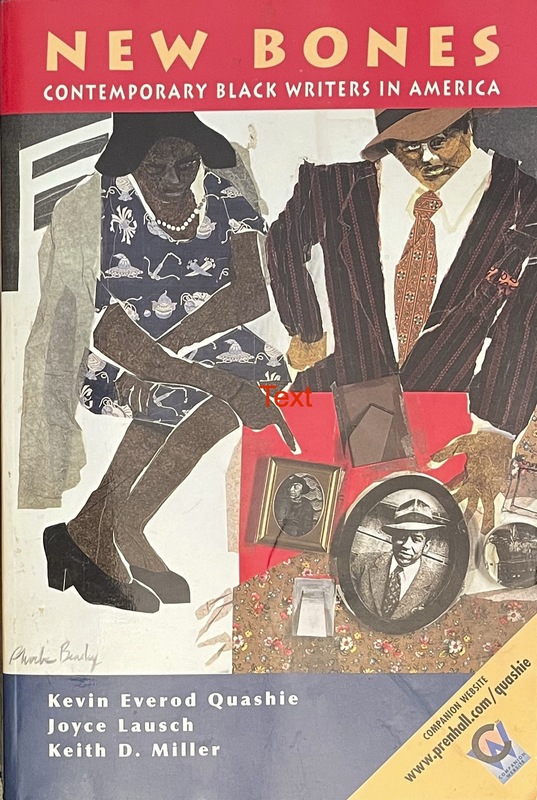

New Bones: Contemporary Black Writers in America

-

This edition

-

"New Bones: Contemporary Black Writers in America" . Ed. Kevin Everod Quashie, R. Joyce Lausch, and Keith D. Miller. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001. xviii+1,128 pp.

-

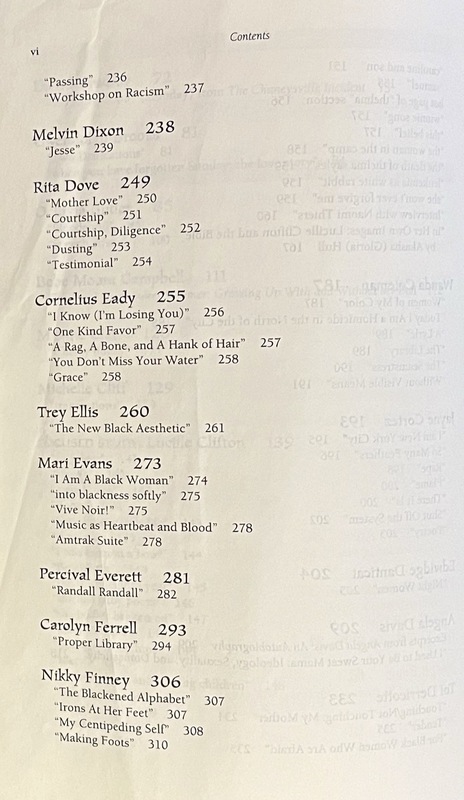

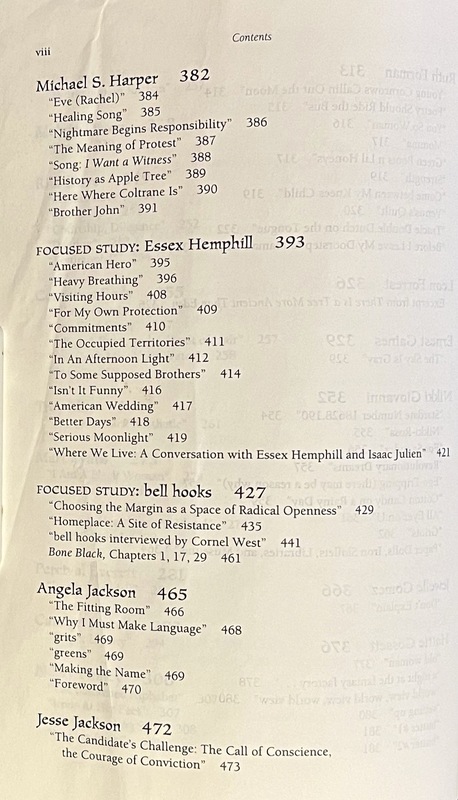

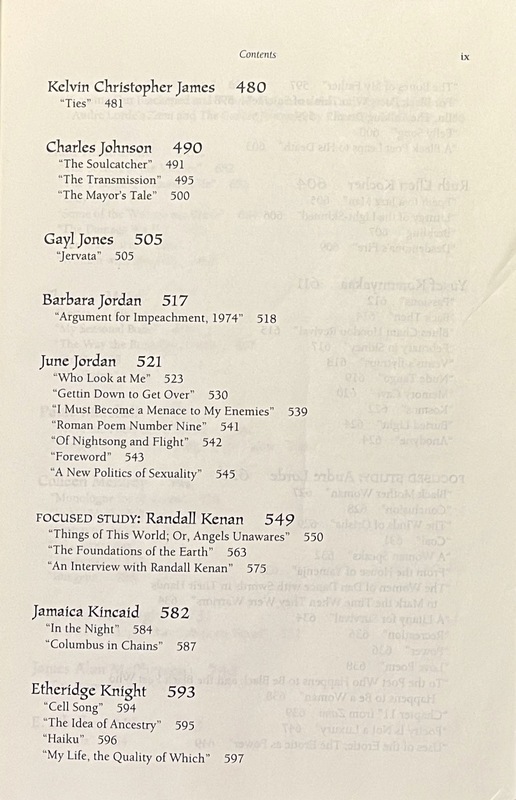

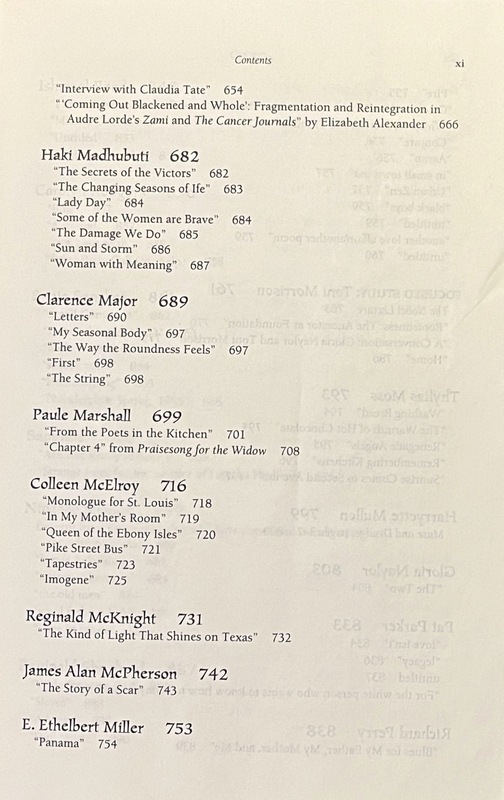

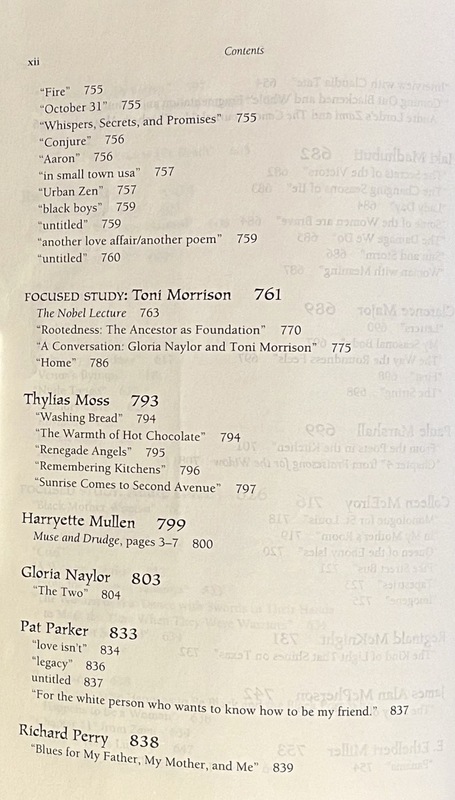

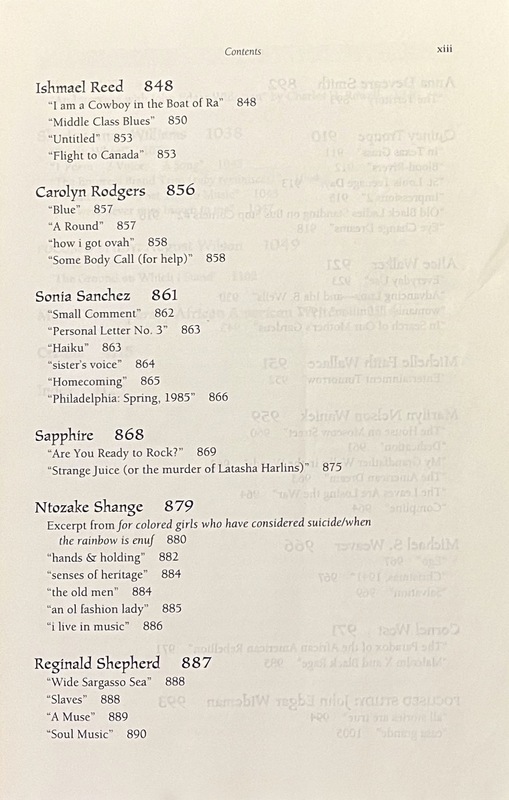

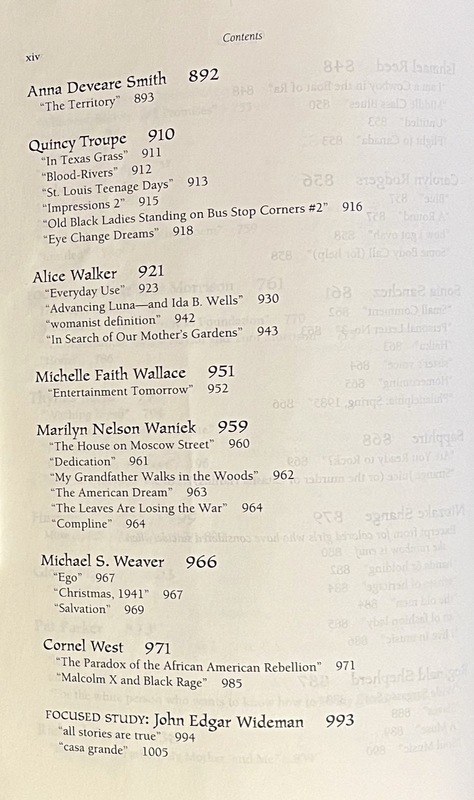

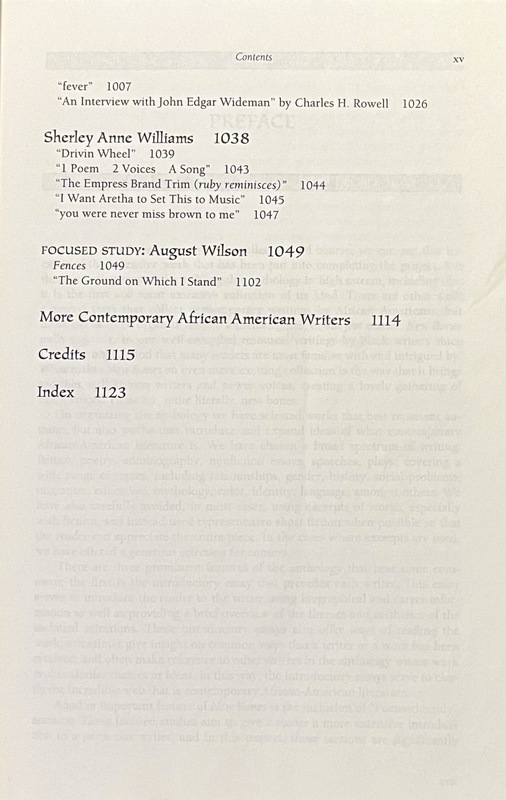

Table of contents

-

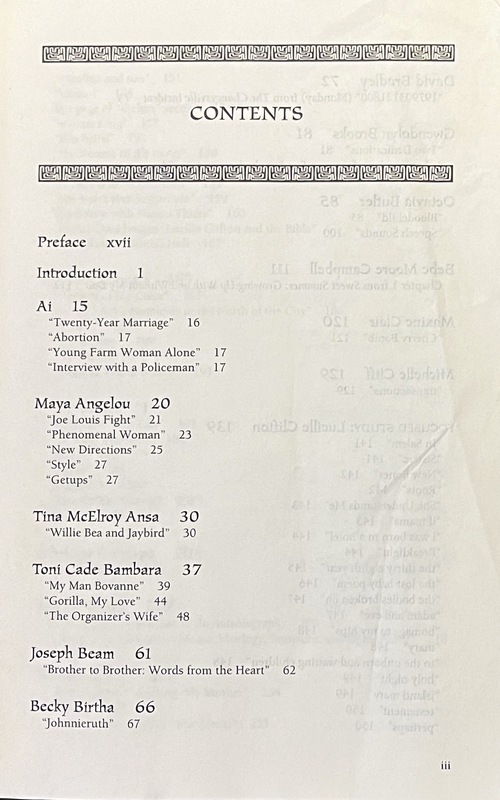

● Preface

● Kevin Everod Quashie, R. Joyce Lausch, and Keith D. Miller / Introduction

● Ai / Twenty-Year Marriage

● Ai / Abortion

● Ai / Young Farm Woman Alone

● Ai / Interview with a Policeman

● Maya Angelou / Joe Louis Fight

● Maya Angelou / Phenomenal Woman

● Maya Angelou / New Directions

● Maya Angelou / Style

● Maya Angelou / Getups

● Tina McElroy Ansa / Willie Bea and Jaybird

● Toni Cade Bambara / My Man Bovanne

● Toni Cade Bambara / Gorilla, My Love

● Toni Cade Bambara / The Organizer's Wife

● Joseph Beam / Brother to Brother: Words from the Heart

● Becky Birtha / Johnnieruth

● David Bradley / from "The Chaneysville Incident" (excerpt: "197903121800" (Monday))

● Gwendolyn Brooks / Two Dedications

● Gwendolyn Brooks / when you have forgotten Sunday: the love story

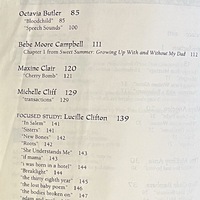

● Octavia Butler / Bloodchild

● Octavia Butler / Speech Sounds

● Bebe Moore Campbell / from "Sweet Summer: Growing Up With and Without My Dad" (excerpt: chapter 1)

● Maxine Clair / Cherry Bomb

● Michelle Cliff / transactions

Focused study

● Lucille Clifton / In Salem

● Lucille Clifton / Sisters

● Lucille Clifton / New Bones

● Lucille Clifton / Roots

● Lucille Clifton / She Understands Me

● Lucille Clifton / if mama

● Lucille Clifton / i was born in a hotel

● Lucille Clifton / Breaklight

● Lucille Clifton / the thirty eighth year

● Lucille Clifton / the lost baby poem

● Lucille Clifton / the bodies broken on

● Lucille Clifton / adam and eve

● Lucille Clifton / homage to my hips

● Lucille Clifton / mary

● Lucille Clifton / to the unborn and waiting children

● Lucille Clifton / holy night

● Lucille Clifton / island mary

● Lucille Clifton / testament

● Lucille Clifton / perhaps

● Lucille Clifton / caroline and son

● Lucille Clifton / samuel

● Lucille Clifton / last page of "thelma" section

● Lucille Clifton / winnie song

● Lucille Clifton / this belief

● Lucille Clifton / the woman in the camp

● Lucille Clifton / the death of thelma sayles

● Lucille Clifton / leukemia as white rabbit

● Lucille Clifton / she won't ever forgive me

● Lucille Clifton / Interview with Naomi Thiers

● Akasha (Gloria) Hull / In Her Own Images: Lucille Clifton and the Bible

● Wanda Coleman / Women of My Color

● Wanda Coleman / Today I Am a Homicide in the North of the City

● Wanda Coleman / A Lyric

● Wanda Coleman / The Library

● Wanda Coleman / The Seamstress

● Wanda Coleman / Without Visible Means

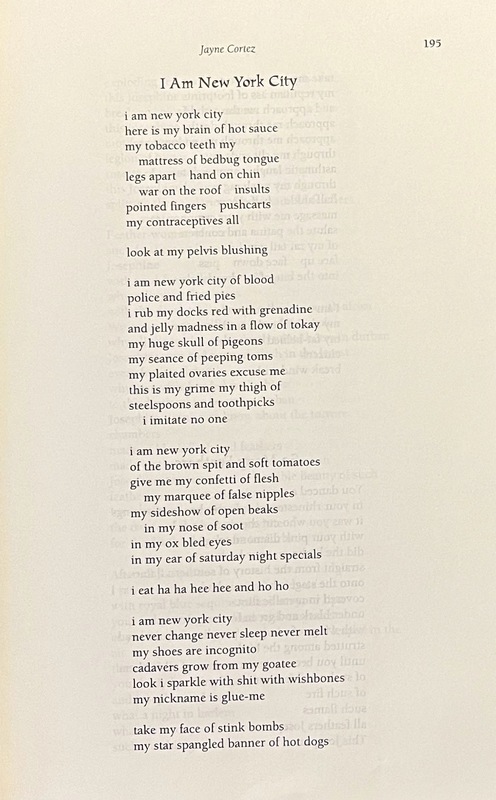

● Jayne Cortez / I Am New York City

● Jayne Cortez / So Many Feathers

● Jayne Cortez / Rape

● Jayne Cortez / Flame

● Jayne Cortez / There It Is

● Jayne Cortez / Shut Off the System

● Jayne Cortez / Poetry

● Edwidge Danticat / Night Women

● Angela Davis / from "Angela Davis: An Autobiography" (excerpts)

● Angela Davis / I Used to Be Your Sweet Mama: Ideology, Sexuality, and Domesticity

● Toi Derricotte / Touching/Not Touching: My Mother

● Toi Derricotte / Tender

● Toi Derricotte / For Black Women Who Are Afraid

● Toi Derricotte / Passing

● Toi Derricotte / Workshop on Racism

● Melvin Dixon / Jesse

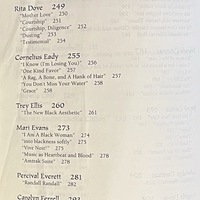

● Rita Dove / Mother Love

● Rita Dove / Courtship

● Rita Dove / Courtship, Diligence

● Rita Dove / Dusting

● Rita Dove / Testimonial

● Cornelius Eady / I Know (I'm Losing You)

● Cornelius Eady / One Kind Favor

● Cornelius Eady / A Rag, a Bone, and a Hank of Hair

● Cornelius Eady / You Don't Miss Your Water

● Cornelius Eady / Grace

● Trey Ellis / The New Black Aesthetic

● Mari Evans / I Am a Black Woman

● Mari Evans / into blackness softly

● Mari Evans / Vive Noir!

● Mari Evans / Music as Heartbeat and Blood

● Mari Evans / Amtrak Suite

● Percival Everett / Randall Randall

● Carolyn Ferrell / Proper Library

● Nikky Finney / The Blackened Alphabet

● Nikky Finney / Irons at Her Feet

● Nikky Finney / My Centipeding Self

● Nikky Finney / Making Foots

● Ruth Forman / Young Cornrows Calling Out the Moon

● Ruth Forman / Poetry Should Ride the Bus

● Ruth Forman / You So Woman

● Ruth Forman / Momma

● Ruth Forman / Green Boots n Lil Honeys

● Ruth Forman / Strength

● Ruth Forman / Come Between My Knees Child

● Ruth Forman / Venus's Quilt

● Ruth Forman / Tracie Double Dutch on the Tongue

● Ruth Forman / Before I Leave My Doorstep to Mama's Grave

● Leon Forrest / from "There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden" (excerpt)

● Ernest Gaines / The Sky Is Gray

● Nikki Giovanni / Stardate Number 18628.190

● Nikki Giovanni / Nikki-Rosa

● Nikki Giovanni / For Saundra

● Nikki Giovanni / Revolutionary Dreams

● Nikki Giovanni / Ego Tripping (there may be a reason why)

● Nikki Giovanni / Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day

● Nikki Giovanni / All Eyez on U

● Nikki Giovanni / Griots

● Nikki Giovanni / Paper Dolls, Iron Skillets, Libraries, and Museums

● Jewelle Gomez / Don't Explain

● Hattie Gossett / old woman

● Hattie Gossett / a night at the fantasy factory . . .

● Hattie Gossett / world view, world view, world view

● Hattie Gossett / setting up

● Hattie Gossett / butter #1

● Hattie Gosset / butter #2

● Michael S. Harper / Eve (Rachel)

● Michael S. Harper / Healing Song

● Michael S. Harper / Nightmare Begins Responsibility

● Michael S. Harper / The Meaning of Protest

● Michael S. Harper / Song: "I Want a Witness"

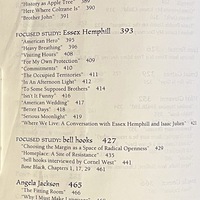

● Michael S. Harper / History as Apple Tree

● Michael S. Harper / Here Where Coltrane Is

● Michael S. Harper / Brother John

Focused study :

● Essex Hemphill / American Hero

● Essex Hemphill / Heavy Breathing

● Essex Hemphill / Visiting Hours

● Essex Hemphill / For My Own Protection

● Essex Hemphill / Commitments

● Essex Hemphill / The Occupied Territories

● Essex Hemphill / In an Afternoon Light

● Essex Hemphill / To Some Supposed Brothers

● Essex Hemphill / Isn't It Funny

● Essex Hemphill / American Wedding

● Essex Hemphill / Better Days

● Essex Hemphill / Serious Moonlight

● Essex Hemphill and Isaac Julien / Where We Live: A Conversation with Essex Hemphill and Isaac Julien

Focused study:

● bell hooks / Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness

● bell hooks / Homeplace: A Site of Resistance

● bell hooks / bell hooks interviewed by Cornel West

● bell hooks / from "Bone Black" (excerpt: chapters 1, 17, 29)

● Angela Jackson / The Fitting Room

● Angela Jackson / Why I Must Make Language

● Angela Jackson / grits

● Angela Jackson / greens

● Angela Jackson / Making the Name

● Angela Jackson / Foreword

● Jesse Jackson / The Candidate's Challenged: The Call of Conscience, the Courage of Conviction

● Kelvin Christopher James / Ties

● Charles Johnson / The Soulcatcher

● Charles Johnson / The Transmission

● Charles Johnson / The Mayor's Tale

● Gayl Jones / Jervata

● Barbara Jordan / Argument for Impeachment, 1974

● June Jordan / Who Look at Me

● June Jordan / Getting Down to Get Over

● June Jordan / I Must Become a Menace to My Enemies

● June Jordan / Roman Poem Number Nine

● June Jordan / Of Nightsong and Flight

● June Jordan / Foreword

● June Jordan / A New Politics of Sexuality

Focused study :

● Randall Kenan / Things of This World; Or, Angels Unawares

● Randall Kenan / The Foundations of the Earth

● Randall Kenan / An Interview with Randall Kenan

● Jamaica Kincaid / In the Night

● Jamaica Kincaid / Columbus in Chains

● Etheridge Knight / Cell Song

● Etheridge Knight / The Idea of Ancestry

● Etheridge Knight / Haiku

● Etheridge Knight / My Life, the Quality of Which

● Etheridge Knight / The Bones of My Father

● Etheridge Knight / For Black Poets Who Think of Suicide

● Etheridge Knight / Ilu, the Talking Drum

● Etheridge Knight / Belly Song

● Etheridge Knight / A Black Poet Leaps to His Death

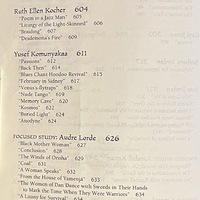

● Ruth Ellen Kocher / Poem to a Jazz Man

● Ruth Ellen Kocher / Liturgy of the Light-Skinned

● Ruth Ellen Kocher / Braiding

● Ruth Ellen Kocher / Desdemona's Fire

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Passions

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Back Then

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Blues Chant Hoodoo Revival

● Yusef Komunyakaa / February in Sidney

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Venus's-flytraps

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Nude Tango

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Memory Cave

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Kosmos

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Buried Light

● Yusef Komunyakaa / Anodyne

Focused study:

● Audre Lorde / Black Mother Woman

● Audre Lorde / Conclusion

● Audre Lorde / The Winds of Orisha

● Audre Lorde / Coal

● Audre Lorde / A Woman Speaks

● Audre Lorde / From the House of Yamenja

● Audre Lorde / The Women of Dan Dance with Swords in Their Hands to Mark the Time When They Were Warriors

● Audre Lorde / A Litany for Survival

● Audre Lorde / Recreation

● Audre Lorde / Power

● Audre Lorde / Love Poem

● Audre Lorde / To the Poet Who Happens to Be Black and the Black Poet Who Happens to Be a Woman

● Audre Lorde / from "Zami" (excerpt: chapter 11)

● Audre Lorde / Poetry Is Not a Luxury

● Audre Lorde / Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power

● Audre Lorde / Interview with Claudia Tate

● Elizabeth Alexander / "Coming Out Blackened and Whole": Fragmentation and Reintegration in Audre Lorde's "Zami" and "The Cancer Journals"

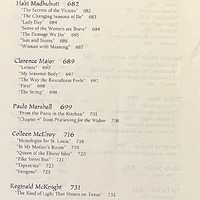

● Haki Madhubuti / The Secrets of the Victors

● Haki Madhubuti / The Changing Seasons of Life

● Haki Madhubuti / Lady Day

● Haki Madhubuti / Some of the Women Are Brave

● Haki Madhubuti / The Damage We Do

● Haki Madhubuti / Sun and Storm

● Haki Madhubuti / Woman with Meaning

● Clarence Major / Letters

● Clarence Major / My Seasonal Body

● Clarence Major / The Way the Roundness Feels

● Clarence Major / First

● Clarence Major / The String

● Paule Marshall / From the Poets in the Kitchen

● Paule Marshall / from "Praisesong for the Widow" (excerpt: chapter 4)

● Colleen McElroy / Monologue for St. Louis

● Colleen McElroy / In My Mother's Room

● Colleen McElroy / Queen of the Ebony Isles

● Colleen McElroy / Pike Street Bus

● Colleen McElroy / Tapestries

● Colleen McElroy / Imogene

● Reginald McKnight / The Kind of Light That Shines on Texas

● James Alan McPherson / The Story of a Scar

● E. Ethelbert Miller / Panama

● E. Ethelbert Miller / Fire

● E. Ethelbert Miller / October 31

● E. Ethelbert Miller / Whispers, Secrets, and Promises

● E. Ethelbert Miller / Conjure

● E. Ethelbert Miller / Aaron

● E. Ethelbert Miller / in small town usa

● E. Ethelbert Miller / Urban Zen

● E. Ethelbert Miller / black boys

● E. Ethelbert Miller / untitled

● E. Ethelbert Miller / another love affair/another person

● E. Ethelbert Miller / untitled

Focused study :

● Toni Morrison / The Nobel Lecture

● Toni Morrison / Rootedness: The Ancestors as Foundation

● Gloria Naylor and Toni Morrison / A Conversation: Gloria Naylor and Toni Morrison

● Thylias Moss / Washing Bread

● Thylias Moss / The Warmth of Hot Chocolate

● Thylias Moss / Renegade Angels

● Thylias Moss / Remembering Kitchens

● Thylias Moss / Sunrise Comes to Second Avenue

● Harryette Mullen / from "Muse and Drudge" (excerpt: pp. 3-7)

● Gloria Naylor / The Two

● Pat Parker / love isn't

● Pat Parker / legacy

● Pat Parker / untilted

● Pat Parker / For the white person who wants to know how to be my friend

● Richard Perry / Blues for My Father, My Mother, and Me

● Ishmael Reed / I Am a Cowboy in the Boat of Ra

● Ishmael Reed / Middle Class Blues

● Ishmael Reed / Untitled

● Ishmael Reed / Flight to Canada

● Carolyn Rodgers / Blue

● Carolyn Rodgers / A Round

● Carolyn Rodgers / how i got ovah

● Carolyn Rodgers / Some Body Call (for help)

● Sonia Sanchez / Small Comment

● Sonia Sanchez / Personal Letter No. 3

● Sonia Sanchez / Haiku

● Sonia Sanchez / sister's voice

● Sonia Sanchez / Homecoming

● Sonia Sanchez / Philadelphia: Spring, 1985

● Sapphire / Are You Ready to Rock?

● Sapphire / Strange Juice (or the murder of Latasha Harlins)

● Ntozake Shange / from "for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf" (excerpt)

● Ntozake Shange / hands & holding

● Ntozake Shange / senses of heritage

● Ntozake Shange / the old men

● Ntozake Shange / an ol fashion lady

● Ntozake Shange / i live in music

● Reginald Shepherd / Wide Sargasso Sea

● Reginald Shepherd / Slaves

● Reginald Shepherd / A Muse

● Reginald Shepherd / Soul Music

● Anna Deveare Smith / The Territory

● Quincy Troupe / In Texas Grass

● Quincy Troupe / Blood-Rivers

● Quincy Troupe / St. Louis Teenage Days

● Quincy Troupe / Impressions 2

● Quincy Troupe / Old Black Ladies Standing on Bus Stop Corners #2

● Quincy Troupe / Eye Change Dreams

● Alice Walker / Everyday Use

● Alice Walker / Advancing Luna--and Ida B. Wells

● Alice Walker / womanist definition

● Alice Walker / In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens

● Michelle Faith Wallace / Entertainment Tomorrow

● Marilyn Nelson Waniek / The House on Moscow Street

● Marilyn Nelson Waniek / Dedication

● Marilyn Nelson Waniek / My Grandfather Walks in the Woods

● Marilyn Nelson Waniek / The American Dream

● Marilyn Nelson Waniek / The Leaves Are Losing the War

● Marilyn Nelson Waniek / Compline

● Michael S. Weaver / Ego

● Michael S. Weaver / Christmas, 1941

● Michael S. Weaver / Salvation

● Cornel West / The Paradox of the African American Rebellion

● Cornel West / Malcolm X and Black Rage

Focused study :

● John Edgar Wideman / all stories are true

● John Edgar Wideman / casa grande

● John Edgar Wideman / fever

● Charles H. Rowell / An Interview with John Edgar Wideman

● Sherley Anne Williams / Drivin' Wheel

● Sherley Anne Williams / 1 Poem 2 Voices A Song

● Sherley Anne Williams / The Empress Brand Trim ("ruby reminiscences")

● Sherley Anne Williams / I Want Aretha to Set This to Music

● Sherley Anne Williams / you were never miss brown to me

Focused study :

● August Wilson / "Fences"

● August Wilson / The Ground on Which I Stand

● More Contemporary African American Writers

● Credits

● Index

-

About the anthology

-

● Features 77 authors, 7 of whom (Lucille Clifton, Essex Hemphill, bell hooks, Randall Kenan, Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison, John Edgar Wideman) are given "focused study," to give "a more extensive introduction" to their work.

● Includes authors who work in various genres: "poets, fiction-writers, biographers, essayists, orators, and playwrights" (Ervin 2001: 268).

-

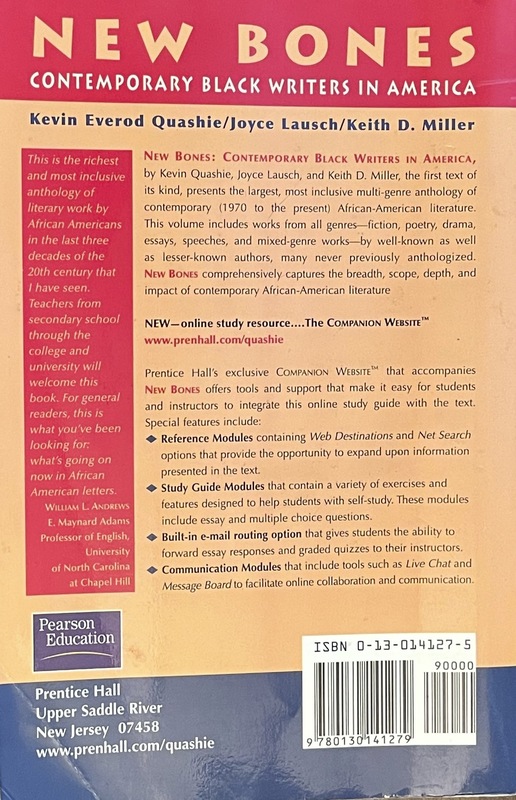

Publisher's description

-

● "The first of its kind, this volume presents the largest, most inclusive multi-genre anthology of contemporary (1970 to the present) African-American literature available. Unlike all other collections of contemporary Black literature (which are genre-specific), this volume includes works from all genres--fiction, poetry, drama, essays, speeches, and mixed-genre works--by important, well-known authors as well as by significant lesser-known authors, many never previously anthologized. It comprehensively captures the breadth, the scope, the depth, and the impact of contemporary African-American literature. Features works (mostly whole works, not just excerpts) by important, well-known authors, such as by Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Audre Lore, August Wilson, Octavia Bintler, Gloria Naylor, Paule Marshall, John Edgar Wideman, Gwendolyn Broaks; and by lesser-known, but excellent authors, such as Michelle Cliff, Wanda Coleman, Randall Kenan, Essex Hemphill, Ruth Forman. Special Focused Writers sections provide an extended look at a writer's contributions, and includes interviews and critical essays along with a large selection of material. A General introductory essay situates the selections and the whole field; and introductory critical essays and headnotes for each writer introduce each author's selections (i.e., the writer's career, influences, impact, and themes), and locates the works included within the writer's entire body of work. For anyone interested in contemporary African-American literature or American literature in general."

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

● Donalson, Melvin. "African American Review" 36.1 (Spring 2002): 176.

Donalson sees the anthology's "inclusiveness" as its "greatest strength": "With a generous representation of the traditional genres of poetry, fiction, and drama, the anthology also highlights literary theory, speeches, gay and lesbian writings, popular/commercial writings, and autobiography. The editors have assembled a diverse group of authors, introducing each with critical headnotes that assess both biographical backgrounds and the literary value of the included selections. In this way, the anthology takes a bold step in defining 'contemporary' as being the past thirty years [1970-2000] and selecting works that best represent those decades" (176).

He sees the alphabetical arrangement of the contents (by authors' last names) as the biggest weakness of the volume: an arrangement by chronology, genre, or thematic or stylistic affinities would be preferable. The alphabetical arrangement "discourages an evaluation of the connections and interdependence of artistic styles, literary movements, and cultural/political themes. . . . For a new or undergraduate reader of black literature, this type of compilation obscures the inextricable association among the newer and older voices during the past thirty years and before. At the same time, at the text's end, a single page includes a listing of names of 'Additional Contemporary Authors' without any context to assess or pursue the cursory amalgamation of names" (176).

-

● Ervin, Hazel Arnette. "CLA Journal" 45.2 (Dec. 2001): 268-71.

The editors emphasize how "extensive" the collection is: this invites scrutiny of what is missing from the anthology. Ervin remarks that "the editors do not move much beyond the existing canon of contemporary writers"; the editors include several works by some authors, "while other acclaimed and often anthologized contemporary writers such as J. California Cooper, Thulani Davis, Henry Dumas, and Alex Pate are excluded. Missing among the newer voices are established writers Kevin Young and Greg Tate. The editors also call attention to the wide range of topics in 'New Bones,' and in doing so, they force readers to question: Should not the contemporary African American writer be acknowledged as one concerned with, for instance, death, marriage, childhood innocence and experiences, and laughter, as well?" (269).

Ervin also calls for greater specification of what the editors mean by a writer's use of "repetition" or of "the language and rhetoric of the black church" (269-70). Ervin also objects to the anthology's presentation of the visual artworks included in it: she argues that Richard Powell's 1988 article "The Blues Aesthetic: Black Culture and Modernism" serves "as a model on how to use the blues to critique visual paintings. Yet the editors of 'New Bones' place paintings by Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, and Gordon Parks and a sculpture by Elizabeth Catlett in an obscure place in the anthology, as if to suggest, unfortunately, that there is no continuity in evaluative criteria in the African American poetic tradition when it comes to visual art" (270).

Ervin seems to take issue with the editors's description of their anthology as "the first and most extensive collection of its kind [i.e., across multiple genres of writing]" (quoted 268): she notes, at the start of her review, the presentation of contemporary African American literature in 'Breaking Ice: An Anthology of Contemporary African American Fiction,' edited by Terry McMillan; 'Brotherman: The Odyssey of Black Men in America,' edited by Herb Boyd and Robert L. Allen; and even sections of 'Black Writers in America,' edited by Richard Barksdale and Keneth Kinnamon" (268) and then concludes the review by remarking that: "In African American culture, literary ancestors serve as inspiriting influences. . . . The editors of 'New Bones' appear distanced from their literary ancestors (e.g., McMillan, Boyd, Allen, Barksdale and Kinnamon)--distanced, unfortunately, as they attempt earnestly to make the reader aware of the 'need' for newer black voices in the canon of contemporary African American literature; of the 'need' to include in our discussions visual art as well as literary art by contemporary African Americans; of the 'need' to deepen aesthetic approaches to contemporary African American literature; and of the 'need' to utilize the Web in our teachings of contemporary African American literary art (visual, oratorical, and written)" (270-71).

-

Item Number

-

A0354

-

Acknowledgments

-

With thanks to Renee Kingan, who contributed the images for this entry.