-

Title

-

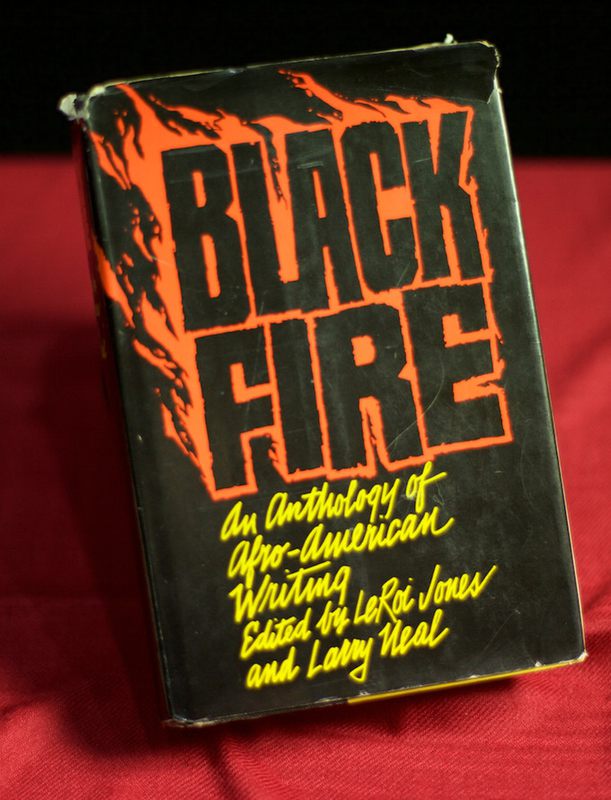

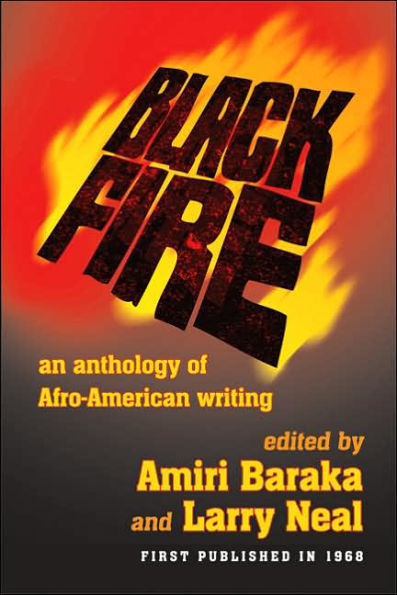

Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing

-

This edition

-

"Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing" . Comp. LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and Larry Neal. New York: Morrow, 1968. xviii+670 pp.; repr. 1971 (paperback), with "Note to first paperback edition."

-

Other editions, reprints, and translations

-

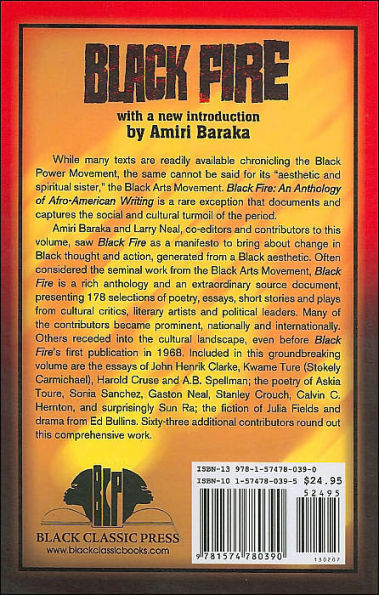

• Repr. Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2007. xxiv+670 pp.

-

Table of contents

-

[Part I]. Essays -- The development of the black revolutionary artist / James T. Stewart -- Reclaiming the lost African heritage / John Henrik Clarke -- African responses to Malcolm X / Leslie Alexander Lacy -- Revolutionary nationalism and the Afro-American / Harold Cruse -- The new breed / Peter Labrie -- Dynamite growing out of their skulls / Calvin C. Hernton -- Black power -- a scientific concept whose time has come / James Boggs -- Toward Black liberation / Stokely Carmichael -- The screens / C.E. Wilson -- Travels in the South: a cold night in Alabama / William Mahoney -- The tide inside, it rages! / Lindsay Barrett -- Not just whistling Dixie / A.B. Spellman -- The Fellah, the chosen ones, the guardian / David Llorens -- Brainwashing of black men's minds / Nathan Hare -- [Part II]. Poetry -- Charles Anderson -- Richard W. Thomas -- Ted Wilson -- James T. Stewart -- Calvin C. Hernton -- Sun-Ra -- Lethonia Gee -- K. William Kgositsile -- David Henderson -- A.B. Spellman -- Sonia Sanchez -- Q.R. Hand -- Ron Welburn -- Joe Goncalves -- Marvin E. Jackmon -- James Danner -- Al Fraser -- Lance Jeffers -- Walt Delegall -- Welton Smith -- LeRoi Jones -- Barbara Simmons -- Larry Neal -- Hart Leroi Bibbs -- Rolland Snellings -- Carol Freeman -- Kirk Hall -- Edward S. Spriggs -- Henry Dumas -- Reginald Lockett -- Odaro -- S.E. Anderson -- Clarence Franklin -- Jay Wright -- Yusuf Rahman -- Rudy Bee Graham -- Lefty Sims -- Lebert Bethune -- Yusef Iman -- Norman Jordan -- Stanley Crouch -- Frederick J. Bryant, Jr. -- Sam Cornish -- Clarence Reed -- Albert E. Haynes, Jr. -- Lorenzo Thomas -- Gaston Neal -- L. Goodwin -- Ray Johnson -- Bob Bennett -- Ahmed Legraham Alhamisi -- D.L. Graham -- Victor Hernandez Cruz -- Jacques Wakefield -- Kuwasi Balagon -- Bobb Hamilton -- [Part III]. Fiction -- Fon / Henry Dumas -- A love song for seven little boys called; Sam / C.H. Fuller, Jr. -- Not your singing, dancing spade / Julia Fields -- That she would dance no more / Jean Wheeler Smith -- Life with red top / Ronald L. Fair -- Sinner man where you gonna run to? / Larry Neal -- Ain't that a groove / Charlie Cobb -- [Part IV]. Drama -- We own the night / Jimmy Garrett -- Flowers for the trashman / Marvin E. Jackmon -- Black ice / Charles Patterson -- Notes from a savage god / Ronald Drayton -- Nocturne on the Rhine / Ronald Drayton -- Madheart / LeRoi Jones -- Prayer meeting or the first militant minister / Ben Caldwell -- How do you do / Ed Bullins -- The leader / Joseph White -- The suicide / Carol Freeman -- [Part V]. An afterword -- And Shine swam on / Larry Neal.

-

About the anthology

-

• "On the credits page, acknowledgment is made to several publications for granting reprinting rights. The two most frequent sources for reprints were "Negro Digest" and "Liberator". The majority of the other acknowledged reprints are from Black publications as well" (Rambsy 2004: 183).

• "At the end of this anthology of recent black American poetry, fiction, drama and non-fiction (essays), the editors give bio-bibliographical sketches (pp. 657-670) of the numerous young writers of the New Black Aesthetic. Some of them are not published elsewhere" (Rowell 1972: 39).

-

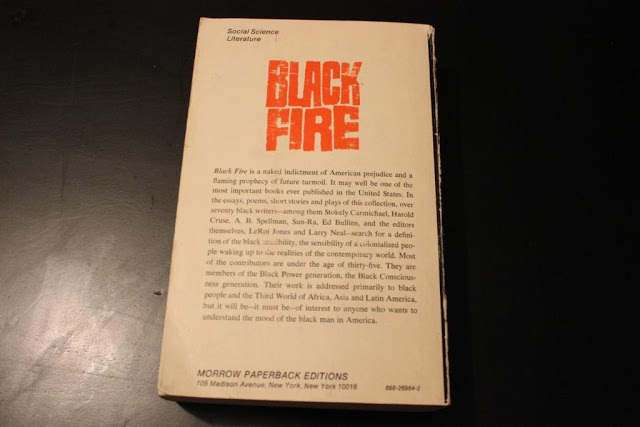

Publisher's description

-

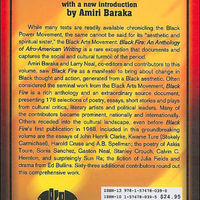

● The back cover of the 2007 Black Classic edition of this anthology tells us that, "While many texts are readily available chronicling the Black Power Movement, the same cannot be said for its 'aesthetic and spiritual sister,' the Black Arts Movement. "Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing" is a rare exception that documents and captures the social and cultural turmoil of the period."

● This sense of the uniqueness of "Black Fire" might be contrasted with Howard Rambsy's argument that the Black Arts Movement acquired public definition through the plethora of anthologies presenting the black writing of the period: writing on "The Golden Age of Anthologies featuring Poetry" on his "Cultural Front" blog (see link below), Rambsy states: "Between 1968 and 1975 . . . , more than 60 anthologies featuring black poetry appeared in print. The publication of so many anthologies during a relatively short period of time accentuated the idea that the Black Arts Movement was in fact a movement. Collectively, the anthologies helped display the idea of a united front among a large and diverse range of African American poets. The anthologies also assisted in establishing contemporary poets such as Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, and Haki Madhubuti as central figures. . . . The anthologies established or solidified tribute and historical poems as well as poems about black music as central types of African American poetry. Because of their influential authority in designating literary value and keeping a select group of poems and poets in print, the anthologies operated as important forces in the formation of a canon of black poetry. Never before and in no years since have so many anthologies featuring African American poetry appeared in print."

-

Cultural Front (blog)

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

• Sackett, S. J. "Negro American Literature Forum" 8.3 (1974): 252-53.

-

Commentary on anthology

-

• John Lindberg. "Discovering Black Literature." "North American Review" 254.3 (1969): 51-56:

States that "Black Fire" is "a militant tome distinguished by much articulate writing on the black aesthetic and a wide, but I fear indiscriminate, selection of black poets, unique in printing several short street-theater type of plays from the black arts movement. Black theater is rare in anthologies as much of it is still in performance" (55).

-

• Barbara Christian. “A Rough Terrain: The Case of Shaping an Anthology of Caribbean Women Writers.” The Ethnic Canon: Histories, Institutions, and Interventions. Ed. David Palumbo-Liu. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1995. 241-59. Repr. in New Black Feminist Criticism, 1985-2000. Ed. Gloria Bowles, M. Giulia Fabi, and Arlene R. Keizer. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 2007. 187-203:

Describes this anthology as a result of "the cultural nationalist impetus of the sixties" (192).

-

• Kinnmon (1997: 466) describes this anthology as "the most important collection devoted to a militant, nationalist aesthetic."

-

• Howard Rambsy II. "The New Black Poetry: Origins, Poetics, Technical Production, and Criticism." Diss. Pennsylvania State U, 2004.

• "Larry Neal and Amiri Baraka's anthology "Black Fire" may have been the era's single most influential document in terms of framing the agenda for the New Black // Poetry and its proponents. Published in 1968, "Black Fire" is a multigenre anthology that includes essays, poetry, fiction, and drama. The writings in "Black Fire" cover a range of topics and issues including nationalism, Black music, the effects of anti-black racism, and Black self-determination" (Rambsy 2004: 182-83).

• "Baraka's foreword, which was written in a 'strange new grammar and syntax' [Eugene Redmond, "Drumvoices", 354], promoted the idea of writers as 'poets/philosophers' and Black artists as 'warriors.' More importantly in terms of how the New Black Poetry would be interpreted, Larry Neal's often-cited afterword entitled 'And Shine Swam On' charts the objectives of new Black artists. 'We don't have all the answers,' wrote Neal, 'but have attempted, through // the artistic and political work presented here to confront our problems from what must be called a radical perspective.' Neal went on to make connections and disconnections between African American literary art of the 1960s and past movements or leading African American figures. Neal elaborated on how African American poets utilizing or seeking to utilize radical perspectives in their writings and appeal to Black audiences must incorporate the spirits of Malcolm X and soul musicians such as John Coltrane and James Brown in their literary works. Neal closed his essay by informing readers that 'the artist and the political activist are one. They are both shapers of the future reality' (656). Baraka's foreword and Neal's afterword establish motives and explanations for the poetry and other writings included in their anthology. . . . In addition, the contributors' notes to "Black Fire" allow the writers not only to identify their publication record but also to express their commitments to Black people and various activist organizing projects. Presenting themselves as activists as well as writers allowed the contributors to suggest // that they were not poets in the conventional sense. . . . Like "Black Fire", several other Black arts anthologies such as "Black Spirits" [1972], "We Speak as Liberators" [1970], "The Forerunners" [1975], and "Natural Process" [1971] include biographical sketches that highlight the experience of contributors as poets and as organizers and activists within communities of African Americans. Mentioning their activist involvement with Black folks was as important as revealing their publication record in order for them to assert their identities as New Black Poets" (Rambsy 2004: 183-85).

• In the "Note to the First Paperback Edition of "Black Fire"" (1971), Baraka and Neal "observe that 'It is obvious that work by: Don Lee, Ron Milner, Alicia Johnson, Carl Boissiere, Katibu (Larry Miller), Halisi, Quincy Troupe, Carolyn Rodgers, Jayne Cortez, and Jewel Latimore shd be in this collection.' Unfortunately though, according to the editors, 'various accidents' prevented works by these artists from appearing in the first edition of "Black Fire". The editors then state that 'these devils,' presumably their white editors, claimed that reprint costs were too expensive to include the aforementioned artists in the paperback edition. Thus, the editors expressed their hope // that they could [in]clude the absent writers in the second edition. In a direct address to their Black audiences, they conclude that[,] 'The frustration of working thru these bullshit white people shd be obvious' (Jones and Neal xvi). Baraka's and Neal's critique of their white publisher functions as a humorous and biting rhetorical display. Their note also confirms that the writers were speaking directly to a Black audience or an audience sympathetic to African Americans. The willingness of the editors to openly criticize their publishers and speak of them as 'devils' served to authenticate Baraka and Neal's stance as militant Black artists and enabled them to further mark their anthology as a Black controlled space. Of course, that Black space was also a white space.

"Although seemingly quiet and unassuming in the process, the publishing house, William Morrow, actively contributed to the production of "Black Fire". The officials at William Morrow, not Baraka and Neal, for instance, had the final word on whether the critical 'note to the first paperback edition of "Black Fire"' would appear in the anthology. Maybe, the publisher was not threatened by the comments of the editors. Or perhaps, they figured that including Baraka and Neal's complaint could actually help sell more books. Whatever the case, although the editors were speaking to African Americans, they were able to reach such a wide Black and non-black audience in large part because they spoke on a platform owned and operated by a mainstream white publisher. Actually, quiet as it's kept, William Morrow played a crucial role in publishing key African American and Black arts texts during the 1960s and 1970s. Amiri Baraka's "Blues People", "Black Music", his plays "The Dutchman" and "The Slave", Harold Cruse's "The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual", volumes of poetry by Nikki Giovanni, Stephen Henderson's "Understanding the New Black Poetry", and plays by Ed Bullins were all published by William Morrow. // Grove Press, Random House, and Doubleday collectively as ["sic"] played significant roles in publishing African American and Black arts literature during the era. Whereas Black aritists often promoted African American institution-building and encouraged writers to publish with Black owned presses, the national exposure the Black Arts Movement received was definitely aided by the fact that white mainstream publishers provided sites for the writings. Thus, one aspect of accounting for the technical production of 'the New' African American anthologies of the 1960s and 1970s involves understanding the collaboration between Black artists and mainstream publishers" (Rambsy 2004: 185-87).

-

• James Smethurst and Howard Rambsy II. "Reform and Revolution, 1965-1976: The Black Aesthetic at Work." "The Cambridge History of African American Literature". Ed. Maryemma Graham and Jerry W. Ward, Jr. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011:

• ""Black Fire" (1968) owed much of its conception, terminology, and inspiration to BARTS [the Black Arts Repertory Theatre, founded by Amiri Baraka in Harlem in 1965]" (Smethurst & Rambsy 2011: 433)

• ""Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing" (1968) . . . and "The Black Aesthetic" (1971) . . . exemplify the confluence of creative artists and intellectuals who committed themselves to generating a culturally distinct body of artistic productions for the benefit of black audiences. . . . On the one hand, poets, playwrights, fiction writers, and essayists composed works that celebrated African American culture, critiqued anti-black racism, and promoted black liberation. At the same time, anthologists, magazine editors, and publishers created or sustained venues for the wide transmission of black literary art" (Smethurst & Rambsy 2011: 405)

• "What made "Black Fire" so influential, in part, was its appearance in 1968, when large numbers of people expressed a burning rage regarding the conditions of African Americans. The contributors in Neal and Baraka's collection seemed to embody the spirit of rebellion and revolution that engulfed cities across the nation as black people rioted in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968" (Smethurst & Rambsy 2011: 405).

-

• Opal J. Moore. "Redefining the Art of Poetry." "The Cambridge History of African American Literature". Ed. Maryemma Graham and Jerry W. Ward, Jr. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011.

"The seminal collection "Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Poetry" (1968), edited by LeRoi Jones and Larry Neal, presented a detailed articulation of the [Black Arts] movement's priorities and plan as argued in critical essays and demonstrated in poetry, fiction, and drama; it also revealed the masculine imagination of the project. Of the seventy-seven writers included, five are women whose work takes no issue with the men. Nikki Giovanni is notably absent from the collection, as are June Meyer (later known as June Jordan) and Audre Lorde, who were writing and publishing in the 1960s. Jordan's anthology "Soulscript" (1970) served as a counterpoint, since it included young, unknown poets as well as many of Jordan's contemporaries, especially those excluded from "Black Fire" such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Giovanni, and Lorde. "Soulscript" also broadened its scope to include literary elders and predecessors Countee Cullen, James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, and more. . . . Gwendolyn Brooks would not have been considered for inclusion in "Black Fire", despite or perhaps because of her established (and establishment) career success" (503).

-

See also

-

• Rambsy, Howard, II. "Understanding the 'New' African American Anthologies." In "The New Black Poetry: Its Origins, Poetics, Technical Production, and Criticism." Diss. Penn State University, 2004. 176-92. "ProQuest Dissertations".

• "Soulscript" (1970), ed. June Jordan

-

Soulscript: Afro-American Poetry

Soulscript: Afro-American Poetry

-

Cited in

-

• Kinnamon 1997: 466. (cites original edition)

• Indexed in "The Columbia Granger's Index to African-American Poetry" (1999)

-

Item Number

-

A0079

Soulscript: Afro-American Poetry

Soulscript: Afro-American Poetry