-

Title

-

Best Short Stories by Negro Writers: An Anthology from 1899 to the Present

-

This edition

-

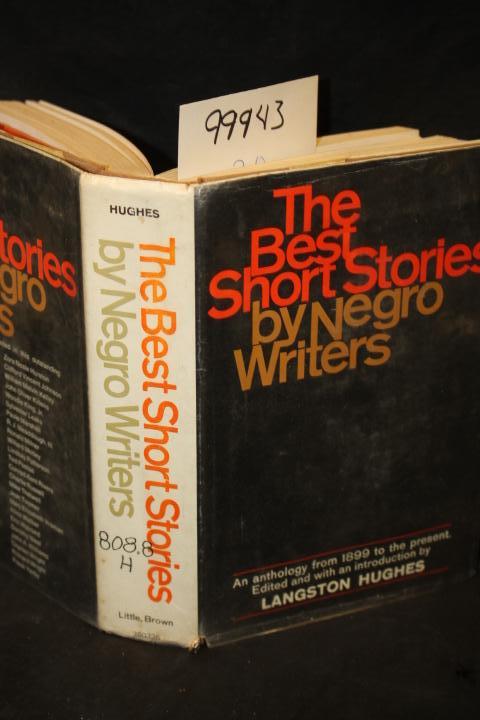

"The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers: An Anthology from 1899 to the Present" . Ed. Langston Hughes. Boston: Little, Brown, 1967. xvii+508 pp.

-

Other editions, reprints, and translations

-

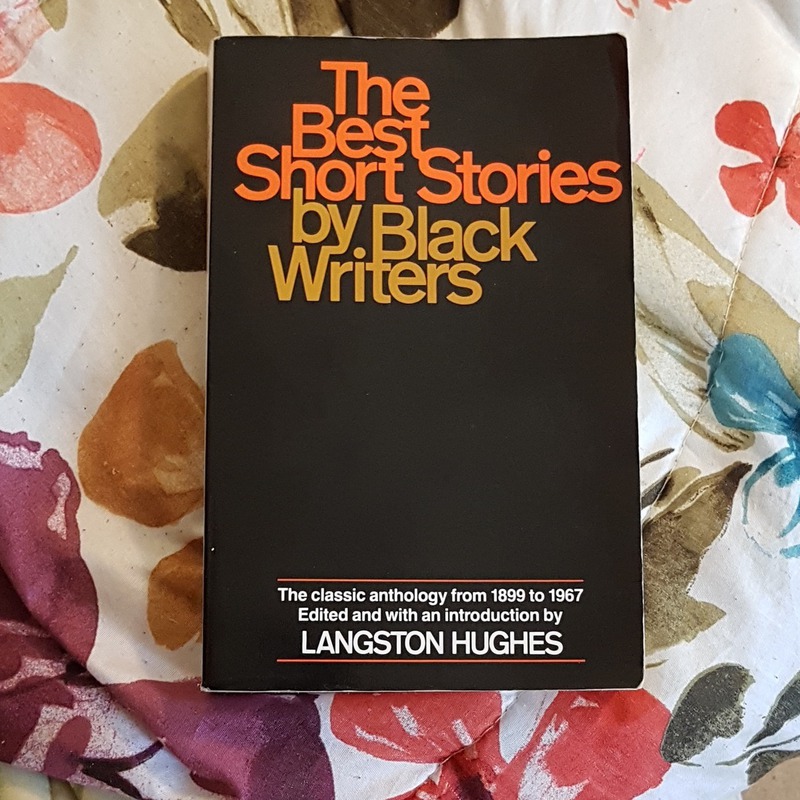

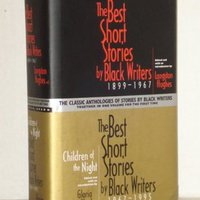

• "The Best Short Stories by Black Writers: 1899-1967". Ed. Langston Hughes. Back Bay Books, 1969.

-

Table of contents

-

The sheriff's children / Charles W. Chesnutt -- The scapegoat / Paul Laurence Dunbar -- Fern / Jean Toomer -- Miss Cynthie / Rudolph Fisher -- The wharf rats / Eric Walrond -- A summer tragedy / Arna Bontemps -- Thank you, m'am / Langston Hughes -- The gilded six-bits / Zora Neale Hurston -- The revolt of the evil fairies / Ted Poston -- Almos' a man / Richard Wright -- Marihuana and a pistol / Chester B. Himes -- The beach umbrella / Cyrus Colter -- The richer, the poorer / Dorothy West -- The almost white boy / Willard Motley -- Afternoon into night / Katherine Dunham -- Flying home / Ralph Ellison -- Come home early, chile / Owen Dodson -- Santa Claus is a white man / John Henrik Clark -- The stick up / John Oliver Killens -- Health card / Frank Yerby -- We're the only colored people here / Gwendolyn Brooks -- The pocketbook game / Alice Childress -- The checkerboard / Alston Anderson -- This morning, this evening, so soon / James Baldwin -- See how they run / Mary Elizabeth Vroman -- The blues begins / Sylvester Leaks -- Son in the afternoon / John A. Williams -- Singing Dinah's song / Frank London Brown -- Duel with the clock / Junius Edwards -- Barbados / Paule Marshall -- The day the world almost came to an end / Pearl Crayton -- An interesting social study / Kristin Hunter -- A new day / Charles Wright -- Quietus / Charlie Russell -- Mother to son / Conrad Kent Rivers -- A long day in November / Ernest J. Gaines -- Miss Luhester gives a party / Ronald Fair -- The death of Tommy Grimes / R.J. Meaddough, III -- Old blues singers never die / Clifford Vincent Johnson -- The only man on Liberty Street / William Melvin Kelley -- Beautiful light and black our dreams / Woodie King, Jr. -- Red bonnet / Lindsay Patterson -- The burglar / Lebert Bethune -- Junkie-Joe had some money / Ronald Milner -- Direct action / Mike Thelwell -- The engagement party / Robert Boles -- To hell with dying / Alice Walker.

-

About the anthology

-

• (from Hughes's introductory note): "The short stories in this volume range from those of the first famous Negro writers in this genre, Charles W. Chesnutt and Paul Laurence Dunbar, widely published at the turn of the century, to the youngest contemporary writers of creative fiction, Ronald Milner, Robert Boles, and Alice Walker. Herein are all the noted names in American Negro writing, including Jean Toomer, Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, Willard Motley, John A. Williams, Frank Yerby, and James Baldwin. This is, as far as I know, the most comprehensive anthology of American Negro short stories to be published anywhere" (quoted in Geraldine E. LaRoque. "Book Marks: Summer Reading." "English Journal" 56.5 [1967]: 766-71, at 768).

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

• Bone, Robert. "Not All Wright and Baldwin." [Rev. of "American Negro Short Stories", ed. Clarke, and of "The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers", ed. Hughes]. "New York Times" 5 March 1967: 293. ("NYTBR" 5 March 1967: 5.)

"There are two kinds of anthologies: those that strive for quality and those that are content with being comprehensive. Both of these books are of the latter inclination. They present, respectively, 31 and 47 stories, as if to make their point by sheer weight of numbers. But in the arts it is quality that counts.

"In failing to develop serious critical standards, the editors have done a disservice to the cause that they, espouse. From a literary standpoint, both collections are undiscriminating. Only one story out of five invites a second reading, or displays a genuine inventiveness, or generates a forceful prose. At the other end of the scale, a second fifth are slight and trivial, or so badly written as to be embarrassing. Who will burn off all this dross to get at the gold? If every good story is surrounded by four that are mediocre or worse, all but the most dedicated readers will give up in despair.

"John Henrik Clarke's bad choices are invariably so for the same reason. He is in trouble whenever he sacrifices his sense of form to his posture of militancy. Langston Hughes knows better, but the canon that he substitutes for militancy is marketability. He has told us elsewhere of his youthful rebellion against his businessman-father, but he reveals in his introduction to this collection how much of his father remains in him. He is "merchandising" these stories; to him they are commodities. As a result, he systematically blurs the distinction between slick or sentimental magazine fiction and the genuine, hand-tooled article.

"Of specific editorial practices, I have three criticisms. The stories are undated, and their publication histories are difficult to ascertain. Both editors pad their collections with excerpts from novels, sometimes without identifying them as such. Finally, writers of the stature of Richard Wright and James Baldwin are poorly represented.

"What about the writers in these two collections? Very few understand that fiction is a way of knowing, not merely a vehicle for the freighting of ideas. Very few respect the imagination; they merely want to tap its power. They subordinate image to idea, so that what emerges is treatise, polemic, racial catechism—anything but revelation, or a deeper vision. Those few, however, are enough, such is their power of penetrating to the core of Negro experience. They are the real artists, and their work is evenly distributed between the two collections.

"In the Clarke volume, six stories are outstanding": Charles Chesnutt's "The Goopherd Grapevine" (1887), Zora Neale Hurston's "The Gilded Six-Bits" (1930s), Albert Murray's "Train Whistle Guitar" (1950s), and from the 1960s: William Melvin Kelley's "Cry for Me," Martin Hamer's "Sarah," and Ernest Gaines's "The Sky Is Gray."

Bone singles out eight stories for praise in Hughes's collection: Paul Laurence Dunbar's "The Scapegoat" (1904), Jean Toomer's "Fern" (from "Cane", 1923), Ralph Ellison's "Flying Home" (1944), and from the 1960s: Ernest Gaines's "A Long Day in November," Paule Marshall's "Barbados," Cyrus Colter's "The Beach Umbrella," Clifford Johnson's "Old Blues Singers Never Die," Clifford Johnson's "Old Blues Singers Never Die," and Lindsay Patterson's "Red Bonnet."

"There was a time when good writing by American Negroes was in such short supply that every anthology was a kind of Amateur Night. Now, with so much talent in the room, it is necessary to become selective. The truth about the comprehensive anthology is that Negro writing has outgrown it. If Clarke and Hughes had recognized the new reality, we might have had tow slender but stunning collections."

• Fuller, Hoyt W. "'Mightier Than the Sword': Three New Anthologies of Negro Writing." [Rev. of "American Negro Short Stories", ed. Clarke (1966); "The Best of Negro Short Stories" ["sic", actually "Best Short Stories by Negro Writers"], ed. Hughes (1967); and "Beyond the Angry Black", ed. Williams (1966; repr. with new postscript, 1969)] "Negro Digest" (Oct. 1966): 43-47. [Google Books preview https://books.google.com/books?id=0zkDAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA44&dq=%22american%20negro%20short%20stories%22%20clarke&pg=PA43#v=onepage&q&f=false ]

"The Negro creative writer in the United States is in an unenviable position. If he, like white writers, chooses, as his raw material his own experiences, and the life reverberating around him, he is likely to find only half-hearted acceptance from editors and publishers. It will make little difference how well he writes, or how fresh and sharp his vision. If he treats his material with honesty, and holds onto his own integrity, what he writes will strike even sympathetic whites as accusatory" (43). Choosing an alternative course, "Many Negro writers have failed because they sought to write 'as writers, not as Negro writers,' not understanding that in a racist and segregationist society—as the American society inherently is—their claim to being merely writers, and not 'Negro writers,' has no meaning at all. For, if their subjects are Negroes, then the facts of life in America will dictate that the racism and segregation be dealt with in one way or another. And, if their subjects are whites, it is altogether probable that white writers know them better and can present them with more clarity, depth and honesty" (44).

John Henrik Clarke tells us that the Negro Renaissance between 1921 and 1931 was "the richest and most productive period in Negro writing in the United States": Fuller comments, "Perhaps this is so; but . . . the Negro Renaissance was not very rich and productive at all by objective standards. . . . Claude McKay, that excellent poet of the period, struggled valiantly to keep a literary journal alive. In the end, Crisis and Opportunity, the non-literary organs of social units floated by white funds provided the only somewhat continuous outlet for Negro writing" (44).

"The Negro writers of the Sixties, some of whom are contributors to the new anthologies, promise a ringing challenge to John Henrik Clarke's contention that the Negro Renaissance was 'the richest and most productive period in Negro writing in the United States.' Already, this group of young writers have ["sic"] produced a stunning body of // work, and many of them have only begun their careers" (45-46).

"Taken together, the stories and articles and poems in [the three anthologies under review] tell more about the history of Negroes in America—and of their relationshp with whites—than shelves of volumes of history and sociology" (47).

• LaRoque, Geraldine E. "Book Marks: Summer Reading." "English Journal" 56.5 (1967): 766-71.

"Langston Hughes' judgement of what constitutes the best stories might be challenged, but his range of authors certainly will make the average reader much more aware of the breadth and depth of the Negro short story. A new reader to this field might also be interested in how often the same themes recur, and perhaps American history buffs will respond to seeing how these authors dramatize historical realities in terms of individuals. The Negro student himself may find in these stories the possibility for deep involvement. 'Thank you, M'am,' Langston Hughes' own story, is surprisingly different from Chesnutt's 'The Sheriff's Children,' Toomer's 'Fern,' and Motley's 'The Almost White Boy' but each finds its place in Hughes' assessment of American Negro writing and writers in his short introduction" (768).

• "Library Journal" 15 April 1967: 1760. (110 words)

"This title must be compared to the recently published "American Negro Short Stories" [1966] by John H. Clarke. Mr. Hughes seems to have made his selections on the basis of literary style or merit. Fifteen of the same authors occur in the two books, but only four stories are in both.... Of the two titles, this new one is more inclusive and the better buy." ("Book Reivew Digest")

• Randall, Dudley. Rev. of "The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers", ed. Langston Hughes. ["Books Noted."] "Negro Digest" (Sept. 1967): 52, 93. [Google Books preview https://books.google.com/books?id=EToDAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA94&dq=%22american%20negro%20short%20stories%22%20clarke&pg=PA52#v=onepage&q&f=false ]

"[I]f these are the best short stories by Negro writers, every one should be of extraordinary merit. Some of these have this quality; others do not. Those that to me are outstanding in this collection are Jean Toomer's 'Fern,' Zora Neale Hurston's 'The Gilded Six-Bits,' Cyrus Colter's 'The Beach Umbrella,' Ralph Ellison's 'Flying Home,' [Frank] Yerby's 'Health Card,' Gwendolyn Brooks' 'We're the Only Colored People Here,' James Baldwin's 'This Morning, This Evening, So Soon,' Mary Elizabeth Vroman's 'See How They run,' John A. Williams' 'Son in the Afternoon,' William Melvin Kelley's 'The Only Man on Liberty Street,' Woodie King's 'Beautiful Light and Black Our Dreams,' Lebert Bethune's 'The Burglar,' and Ronald Milner's 'Junkie Joe Had Some Money.' These are outstanding because, to me, they deeply engage the reader either through characterization, incident, or situation, and even after reading they were not forgotten like froth that appears in a woman's magazine, but continued to reverberate in the memory. Their style was good, and did not irritate through clumsiness, flatness, or imprecision" (52).

Ronald Milner's "Junkie Joe Had Some Money" "is not published here for the first time as stated in the acknowledgements. It appeared years ago in a short-lived magazine published by the Henry brothers of Michigan" (52).

"Perhaps it is best to regard the collection as showing the scope and variety of stories by Negro authors. All the stories are not on the race problem, as one might assume" (52). (Randall mentions nine stories on various aspects of life, but not specifically focused on "the race problem" [52], as well as three—Kristin Hunter's "An Interesting Social Study," Charles Wright's "A New Day," and Charlie Russell's "Quietus"—that "do depict racial relations and confrontations" [93].)

-

Commentary on anthology

-

• Includes 47 stories—50% more than in Clarke's American Negro Short Stories (1966) [see above]: "Eric Walrond, Jean Toomer, Cyrus Colter, Ralph Ellison, and John A. Williams are among the writers appearing in Hughes but not in Clarke. Hughes was always generous in helping younger writers and prescient in evaluating their talent, qualities demonstrated here by his praise of Alice Walker, then in her early twenties, and by his inclusion of her first story, 'To Hell With Dying'" (Kinnamon 1997: 472).

-

Cited in

-

Kinnamon 1997: 472]

-

Item Number

-

A0074

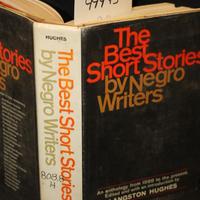

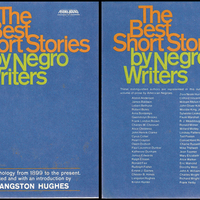

Front cover, spine, back cover (hardcover ed.)

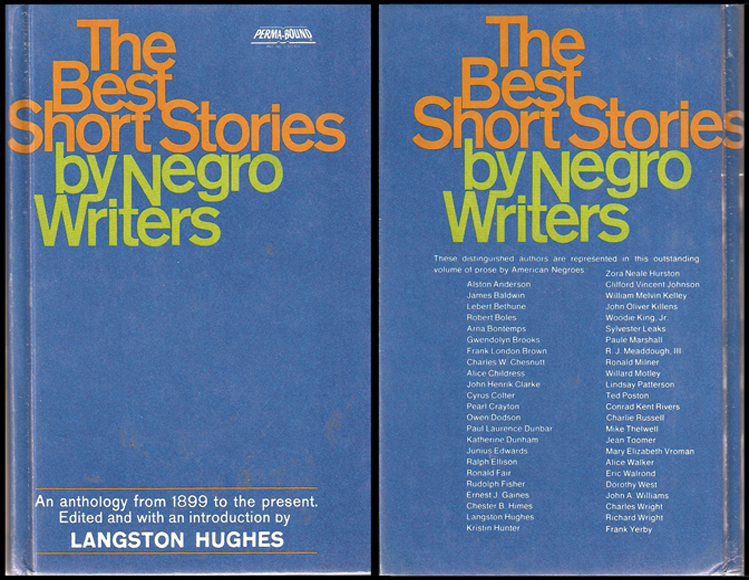

Front cover, spine, back cover (hardcover ed.) Front cover and back cover (perma-bound ed.)

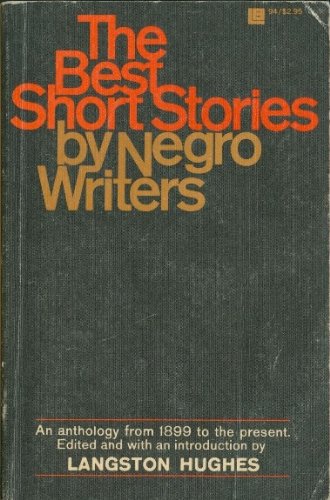

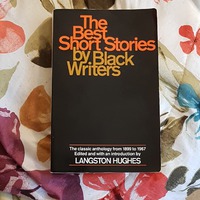

Front cover and back cover (perma-bound ed.) Front cover (paperback ed.)

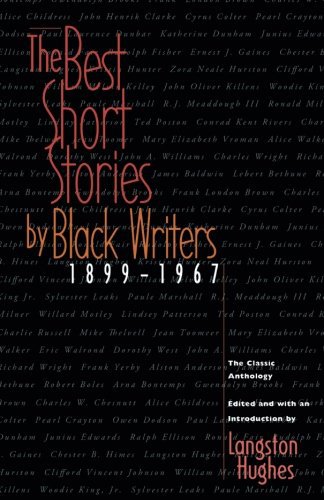

Front cover (paperback ed.) Front cover ("Black Writers") (paperback ed.)

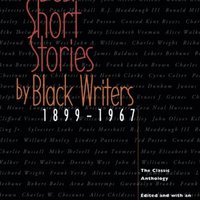

Front cover ("Black Writers") (paperback ed.) Front cover ("Black Writers") (1997 paperback ed.)

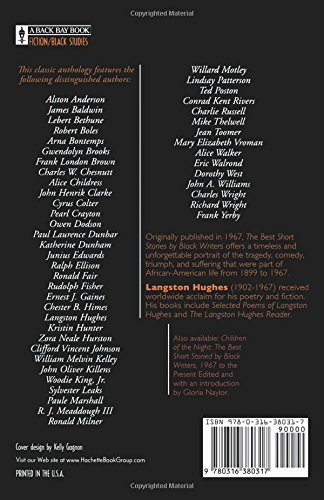

Front cover ("Black Writers") (1997 paperback ed.) Back cover ("Black Writers") (1997 paperback ed.)

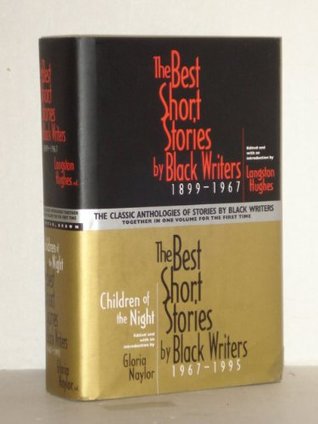

Back cover ("Black Writers") (1997 paperback ed.) Front cover, combined ed. (2002)

Front cover, combined ed. (2002)