-

Title

-

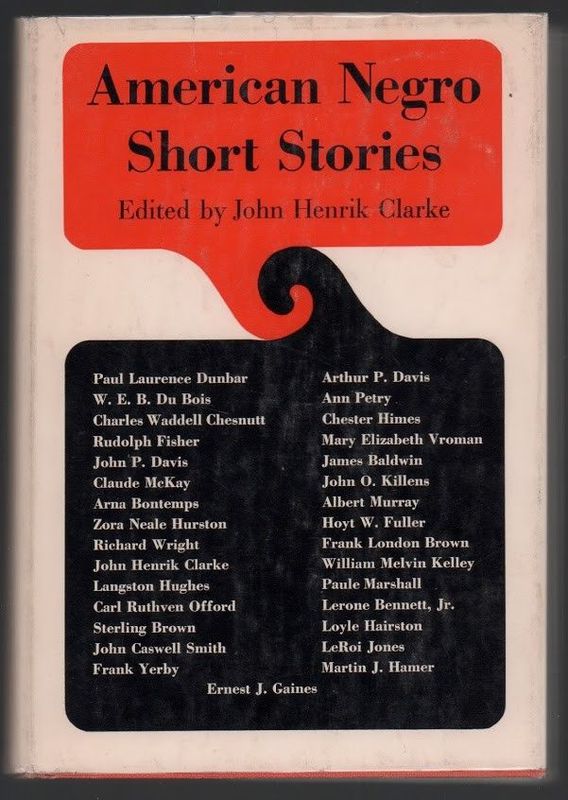

American Negro Short Stories

-

This edition

-

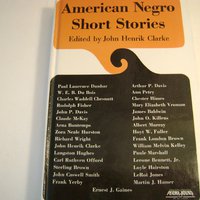

"American Negro Short Stories" . Ed. John Henrik Clarke. New York: Hill & Wang, 1966. xix+355 pp. $5.95; pap. $1.95.

-

Table of contents

-

(copyright information from "Acknowledgments" page)

Acknowledgments (vii-ix) –

Contents (xi-xiii) –

John Henrik Clarke / Introduction [dated May, 1966] (xv-xix) –

Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Lynching of Jube Benson (1-8) –

W. E. B. Du Bois / On Being Crazy [© 1907] (8-10) –

Charles Waddell Chesnutt / The Goophered Grapevine (11-20) –

Rudolph Fisher / The City of Refuge [© 1924] (21-36) –

John P. Davis / The Overcoat [© 1928] (36-41) –

Claude McKay / Truant [© 1932, from "Gingertown" by Claude McKay] (41-54) –

Arna Bontemps / A Summer Tragedy [© 1933] (54-63) –

Zora Neale Hurston / The Gilded Six-Bits [© 1933, by "Story Magazine"] (63-74) –

Richard Wright / Bright and Morning Star [© 1933] (75-108) –

John Henrik Clarke / The Boy Who Painted Christ Black [© 1940] (108-14) –

Langston Hughes / One Friday Morning [First pub. in "The Crisis" (July 1941)] (114-23) –

Carl Ruthven Offord / So Peaceful in the Country [© 1945] (123-30) –

Sterling Brown / And/Or [© 1946] (131-35) –

John Caswell Smith / Fighter [© 1946] (135-47) –

Frank Yerby / The Homecoming [© 1946] (147-56) –

Arthur P. Davis / How John Boscoe Outsung the Devil [© 1947] (156-64) –

Ann Petry / Solo on the Drums [© 1947, by "'47 Magazine of the Year"] (165-69) –

Chester Himes / Mama's Missionary Money [© 1949] (170-75) –

Mary Elizabeth Vroman / See How They Run [© 1951] (176-97) –

James Baldwin / Exodus [© 1952] (197-204) –

John O. Killens / God Bless America [© 1952, by "The California Quarterly"] (204-09) –

Albert Murray / Train Whistle Guitar [© 1953; first published in "New World Writing IV" as "The Luzana Cholly Kick"] (209-26) –

Hoyt W. Fuller / The Senegalese [© 1960] (226-45) –

Frank London Brown / A Matter of Time [© 1962] (245-48) –

William Melvin Kelley / Cry for Me [© 1962, from "Dancers on the Shore", by William Melvin Kelley] (248-63) –

Paule Marshall / Reena [© 1962] (264-82) –

Lerone Bennett, Jr. / The Convert [© 1963] (282-96) –

Loyle Hairston / The Winds of Change [© 1963] (297-304) –

LeRoi Jones / The Screamers [© 1963] (304-10) –

Martin J. Hamer / Sarah [© 1964] (311-21) –

Ernest J. Gaines / The Sky Is Gray [© 1963; repr. from "Negro Digest"] (321-48) –

Biographical Notes (349-55)

-

About the anthology

-

• "Thirty-one stories by Paul Laurence Dunbar, W. E. B. Du Bois, Charles Chesnutt, Claude McKay, Arna Bontemps, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Sterling Brown, Frank Yerby, James Baldwin, LeRoi Jones, John Killens, and others" [ad copy in "College English" 28.1 (1966): front matter. "JSTOR".

This was the only ad for a book of black literature in "College English" in 1966 (Paul Wadden. "Reading the Texts That Read the Profession: Ads for Literature Texts in "College English", 1960-1995." "College Literature" 26.3 (1999): 59-81, at 69. By 1970, however, there was a sudden new attention to black authors and black writings, both in dedicated anthologies and in inclusion of black authors in general anthologies: however limited this inclusion might have been, the presence of such writers was highlighted in the ads for these general anthologies: e.g. an ad for the new edition of the Norton anthology of poetry, "in the great Norton tradition," now featuring poems ranging from "lyrics predating Chaucer to Ishmael Reed's black satire": "College English" 31.4 (Jan. 1970) (Wadden 1999: 70).]

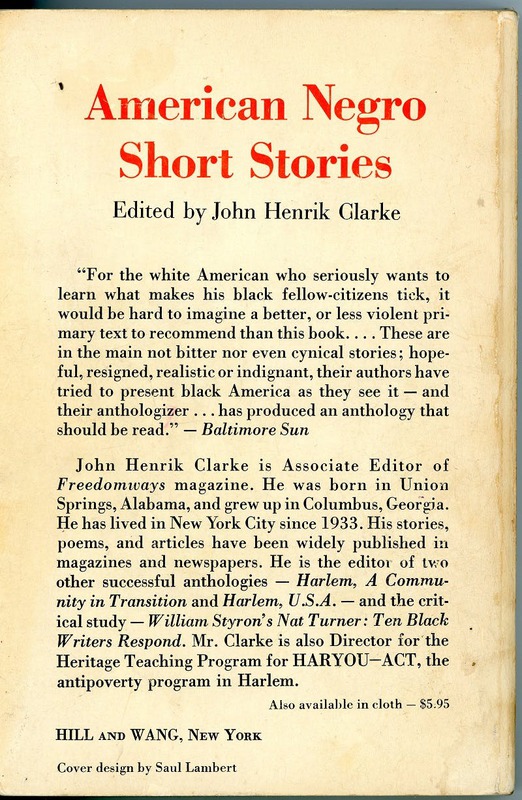

• "For the white American who seriously wants to learn what makes his black fellow-citizens tick, it would be hard to remember ["sic"] a better, or less violent, primary text . . ." – "Balitmore Sunday Sun" [quoted in ad for this anthology in "English Journal" 57.7 (1968): 1082; see also back cover of the anthology]

• "John Henrik Clarke's anthology, "American Negro Short Stories", published in October 1966, is now in its second printing"("Negro Digest" [Feb. 1967]: 50).

• Still in print and priced at $5.95 in 1981 but at $6.95 in 1982, 1983, and 1984 (ad copy in "PMLA" 96.6 [Nov. 1981]: 1238; 97.6 [Nov. 1982]: 1190; 98.6 [Nov. 1983]: 1250; 99.6 [Nov. 1984]: 1344. "JSTOR")

• Dedication: "To my daughter, Nzingha Marie"

• Back cover copy (paperback edition): (full text)

"'For the white American who seriously wants to learn what makes his black fellow-citizens tick, it would be hard to imagine a better, or less violent primary text to recommend than this book. . . . These are in the main not bitter nor even cynical stories; hopeful, resigned, realistic or indignant, their authors have tried to present black America as they see it—and their anthologizer . . . has produced an anthology that should be read.'—"Baltimore Sun" [see review by Jeanne Rose, below]

"John Henrik Clarke is Associate Editor of "Freedomways" magazine. He was born in Union Springs, Alabama, and grew up in Columbus, Georgia. He has lived in New York City since 1933. His stories, poems, and articles have been widely published in magazines and anthologies: "Harlem, A Community in Transition" and "Harlem, U.S.A." Mr. Clarke is also Director for the Heritage Teaching Program for HARYOU-ACT, the antipoverty program in Harlem."

• "Introduction" by John Henrik Clarke (xv-xix) (dated "May, 1966"): (The introduction is actually a lightly revised version of Clarke's 1960 essay, "Transition in the American Negro Short Story." "Phylon" 21.4 (1960): 360-66. "JSTOR")

"The people of the United States, in general, have been reluctant to accept the fact that this is a multi-ethnic nation, and the literature of this nation, when it is honestly seen and understood, reflects this fact. What is called American Negro Literature remains the least understood of that massive body of writings that is called American Literature" (xv).

Re the late 19th century era of Paul Laurence Dunbar and Charles W. Chesnutt: "The period of the slave narrative had passed. Yet, the Negro writer was still an oddity and a stepchild in the eyes of most critics. This attitude continued, in a lessening degree, throughout the richest and most productive period in Negro writing in the United States—the period called the Negro Renaissance, which was mainly the years between 1921 and 1931" (xvi).

Re the Negro Renaissance: "The community of Harlem was the center and spiritual godfather and midwife of this renaissance. The cultural emancipation of the American Negro that began after the First World War was now in full force. The Negro writer discovered a new voice within himself and liked the sound of it. The white writers who had been interpreting Negro life with an air of authority and a preponderance of error looked at last to the Negro writer for their next cue" (xvi).

Re Richard Wright in 1930s and early 1940s: "After the emergence of Richard Wright the double standard for Negro writers was over. Hereafter Negro writers had to stand or fall by the same standards used to evalue the work of white writers. The era of the patronized and pamphered Negro writer had at last come to an end. In the final analysis the closing of this era may be Richard Wright's greatest contribution to the status of Negro writers and to Negro literature" (xviii).

After Wright: "The first short stories of Ralph Ellison exemplify the new tone and vitality of the Negro short stories of this period. (A contribution from Mr. Ellison is regretfully missing from this anthology solely because I could not obtain permission to use any of his work.)" (xviii).

"When Richard Wright died in Paris in 1960 a new generation of Negro writers, partly influenced by him, was beginning to explore, as Ralph Ellison said, 'the full range of American Negro humanity.' . . . [These writers] have questioned and challenged all previous interpretations of American Negro life. In doing so they have created the bais for a new American literature."

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

• Bone, Robert. "Not All Wright and Baldwin." [Rev. of "American Negro Short Stories", ed. Clarke, and of "The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers", ed. Hughes]. "New York Times" 5 March 1967: 293. ("NYTBR" 5 March 1967: 5.) "ProQuest".

"There are two kinds of anthologies: those that strive for quality and those that are content with being comprehensive. Both of these books are of the latter inclination. They present, respectively, 31 and 47 stories, as if to make their point by sheer weight of numbers. But in the arts it is quality that counts.

"In failing to develop serious critical standards, the editors have done a disservice to the cause that they, espouse. From a literary standpoint, both collections are undiscriminating. Only one story out of five invites a second reading, or displays a genuine inventiveness, or generates a forceful prose. At the other end of the scale, a second fifth are slight and trivial, or so badly written as to be embarrassing. Who will burn off all this dross to get at the gold? If every good story is surrounded by four that are mediocre or worse, all but the most dedicated readers will give up in despair.

"John Henrik Clarke's bad choices are invariably so for the same reason. He is in trouble whenever he sacrifices his sense of form to his posture of militancy. Langston Hughes knows better, but the canon that he substitutes for militancy is marketability. He has told us elsewhere of his youthful rebellion against his businessman-father, but he reveals in his introduction to this collection how much of his father remains in him. He is "merchandising" these stories; to him they are commodities. As a result, he systematically blurs the distinction between slick or sentimental magazine fiction and the genuine, hand-tooled article.

"Of specific editorial practices, I have three criticisms. The stories are undated, and their publication histories are difficult to ascertain. Both editors pad their collections with excerpts from novels, sometimes without identifying them as such. Finally, writers of the stature of Richard Wright and James Baldwin are poorly represented.

"What about the writers in these two collections? Very few understand that fiction is a way of knowing, not merely a vehicle for the freighting of ideas. Very few respect the imagination; they merely want to tap its power. They subordinate image to idea, so that what emerges is treatise, polemic, racial catechism—anything but revelation, or a deeper vision. Those few, however, are enough, such is their power of penetrating to the core of Negro experience. They are the real artists, and their work is evenly distributed between the two collections.

"In the Clarke volume, six stories are outstanding": Charles Chesnutt's "The Goopherd Grapevine" (1887), Zora Neale Hurston's "The Gilded Six-Bits" (1930s), Albert Murray's "Train Whistle Guitar" (1950s), and from the 1960s: William Melvin Kelley's "Cry for Me," Martin Hamer's "Sarah," and Ernest Gaines's "The Sky Is Gray."

Bone singles out eight stories for praise in Hughes's collection: Paul Laurence Dunbar's "The Scapegoat" (1904), Jean Toomer's "Fern" (from "Cane", 1923), Ralph Ellison's "Flying Home" (1944), and from the 1960s: Ernest Gaines's "A Long Day in November," Paule Marshall's "Barbados," Cyrus Colter's "The Beach Umbrella," Clifford Johnson's "Old Blues Singers Never Die," Clifford Johnson's "Old Blues Singers Never Die," and Lindsay Patterson's "Red Bonnet."

"There was a time when good writing by American Negroes was in such short supply that every anthology was a kind of Amateur Night. Now, with so much talent in the room, it is necessary to become selective. The truth about the comprehensive anthology is that Negro writing has outgrown it. If Clarke and Hughes had recognized the new reality, we might have had tow slender but stunning collections."

-

• "Choice" 4 (June 1967): 420. (100 words)

-

• Dumetz, Louise P. Rev. of "American Negro Short Stories", ed. Clarke. "Chicago Defender" 8 Oct. 1966: 25. "ProQuest".

"Loud praises should be the lot of editor John Henrik Clarke for this swinging collection of Negro Lore. All of the favorites are included among the 31 Negro authors. There are James Baldwin, Arna Bontemps, Frank London Brown, Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright and Frank Yerby—to mention a few. . . . There are warmth, humor, tragedy, and sadness in these plums of American Negro literature—and they provide an insight into the life, thinking, and aspirations of Negro Americans."

-

• Fuller, Hoyt W. "'Mightier Than the Sword': Three New Anthologies of Negro Writing." [Rev. of "American Negro Short Stories", ed. Clarke (1966); "The Best of Negro Short Stories" ["sic", actually "Best Short Stories by Negro Writers"], ed. Hughes (1967); and "Beyond the Angry Black", ed. Williams (1966; repr. with new postscript, 1969)] "Negro Digest" (Oct. 1966): 43-47. [Google Books preview]

"The Negro creative writer in the United States is in an unenviable position. If he, like white writers, chooses, as his raw material his own experiences, and the life reverberating around him, he is likely to find only half-hearted acceptance from editors and publishers. It will make little difference how well he writes, or how fresh and sharp his vision. If he treats his material with honesty, and holds onto his own integrity, what he writes will strike even sympathetic whites as accusatory" (43). Choosing an alternative course, "Many Negro writers have failed because they sought to write 'as writers, not as Negro writers,' not understanding that in a racist and segregationist society—as the American society inherently is—their claim to being merely writers, and not 'Negro writers,' has no meaning at all. For, if their subjects are Negroes, then the facts of life in America will dictate that the racism and segregation be dealt with in one way or another. And, if their subjects are whites, it is altogether probable that white writers know them better and can present them with more clarity, depth and honesty" (44).

John Henrik Clarke tells us that the Negro Renaissance between 1921 and 1931 was "the richest and most productive period in Negro writing in the United States": Fuller comments, "Perhaps this is so; but . . . the Negro Renaissance was not very rich and productive at all by objective standards. . . . Claude McKay, that excellent poet of the period, struggled valiantly to keep a literary journal alive. In the end, Crisis and Opportunity, the non-literary organs of social units floated by white funds provided the only somewhat continuous outlet for Negro writing" (44).

"The Negro writers of the Sixties, some of whom are contributors to the new anthologies, promise a ringing challenge to John Henrik Clarke's contention that the Negro Renaissance was 'the richest and most productive period in Negro writing in the United States.' Already, this group of young writers have ["sic"] produced a stunning body of // work, and many of them have only begun their careers" (45-46).

"Taken together, the stories and articles and poems in [the three anthologies under review] tell more about the history of Negroes in America—and of their relationshp with whites—than shelves of volumes of history and sociology" (47).

-

Google Books preview

-

• Giles, Louise. "Library Journal" 1 Sept. 1966: 3971. (140 words)

"These 31 stories could well have been limited to about 20: 4 or 5 of them are really poorly done and questionable inclusions. The good ones however, are really good. Among them are 'Exodus' by James Baldwin; 'Train Whistle Guitar' by Albert Murray; 'Cry For Me' by William Melvin Kelley: 'Reena' by Paule Marshall; 'The Screamers' by Leroi Jones. . . . These in themselves make it a worthy collection. Recommended for public and college libraries" ("Book Review Digest")

-

• Hicks, Granville. "Saturday Review" 14 Jan. 1967: 79.

"About a third of the stories center in conflict between Negroes and whites, sometimes violent, sometimes not. Of these the strongest is Richard Wright's 'Bright and Morning Star,' crude but powerful. Another third emphasize the hardships of the Negro people in both South and North. I have been touched by several of these, particularly Arna Bontemps's 'A Summer Tragedy' and Ernest Gaines's 'The Sky is Gray.' If there are few stories of distinction, there are not very many that fall below what we think of as the general level of short-story writing today" ("Book Review Digest")

-

• Hone, Ralph E. "Negro Short Stories." "Los Angeles Times" 25 Dec. 1966: G30. "ProQuest".

"John Henrik Clarke's 'American Negro Short Stories' is a collection of 31 expressive reports of the hopes, dreams, frustrations, fears and angers of American Negroes over the last 60 years. Readers are already aware of the explosiveness resident in the foot-dragging acknowledgement of civil rights in America, but what this book makes crystal-clear is that plight makes fight.

"The theme of many of the major prophets in this little bible is that hope deferred maketh the heart sick. That blindness of injustice gives way to blindness of violence. That inequality of opportunity creates a vacuum which destructive outside forces (like communism) rush in to fill. That human beings must be treatd as human beings. But who hath believed their report? If they have eyes to see, say the angrier young men and women in this collection, why won't they see?"

-

• Hooper, Majorie F. "Journal of Negro History" 53.1 (1968): 90-92. "JSTOR".

"The growing militancy of the Negro American has, in turn, focussed attention upon his literary skill—his ability as a craftsman both to rise above his material in presentation and to remain submerged in it for inspiration. . . . [I]n using his environment so adroitly—the city street, the jazz spot, the country town, the school room, he transfixes his characters and transcends their seemingly dead end existence. A tall order for any artist! Not to speak of a spokesman of an oppressed people" (90-91).

The editor's "all too brief" introduction "lightly sketches the ways [African American] writers have shaped the short story. He speaks first of Paul Lawrence ["sic"] Dunbar and Charles W. Chesnutt. The Harlem Renaissance brought Jean Toomer's "Cane", Langston Hughes' "Ways of White Folks", Zora Neale Hurston's "Mules and Men". The works of men like Claude McKay, Rudolph Fisher, Eric Walrond gleamed in the prolific outpouring which found [its] way into print chiefly in the stimulating, receptive magazines, "Opportunity" and "Crisis". The short story reached a high water mark with Richard Wright, a craftsman almost without parallel whose contribution is undeniable: 'After the emergence of Richard Wright the double standard for Negro writers was over. Hereafter Negro writers had to stand or fall by the same standards used to evaluate the work of white writers.' There is no dearth of present day writers to carry on the tradition. Fine stories from the modern group appear in this collection, and we can enjoy anew the skill of writers like James Baldwin, Albert Murray, Arthur Davis as well as the variety of their views of life" (91).

The reviewer then goes on to mention stories concerned with particular themes—whether injustice, or the experiences of children, or city life (91-92). "Some stories are uniquely Negro. Others like 'A Summer Tragedy' (Arna Bontemps) and 'So Peaceful in the Country' (Carl Offord) describe universal problems of human beings" (92).

"Mr. Clarke, Associate Editor of "Freedomways", has performed for us a number of services: he has focussed our attention on the short story as a literary genre in the hands of the artist sensitive to human problems. By drawing together thirty-six talented writers and one sample apiece of their output, he has demonstrated a body of literature worthy of further study and publication, certainly worthy of inclusion in any anthology of American literature or in any study of American literature, whether expository or historical. And he has shown us that the creativity of the minority writer has not lain dormant or undeveloped behind the curtain of discrimination that America has so arbitrarily lowered between him and his race and the rest of society" (92).

-

• Kaiser, Ernest. "Pioneering Anthology." "Freedomways" 7.1 (Winter 1967): 84-87. JSTOR.

-

JSTOR

-

• Kenny, Herbert A. "Today's Short Stories." "Boston Globe" 9 Oct. 1966: A21. "ProQuest Historical Newspapers":

"a most interesting and instructive collection put together by John Henrik Clarke, who has written with brilliance about Harlem. It is marred by the absence of Ralph Ellison, and Clarke apologizes for the omission, saying Ellison's publishers would not grant the necessary permission. . . . A major justification for putting together such a collection—apart from reasons of literary history—is that such a book can go far in smashing the stereotypes in which the majority of the white population casts the Negro. One has only to read W. E. B. Du Bois' contribution 'On Being Crazy,' to realize that the same tragic illogic, madness that prevailed in the South in 1907 prevails too generally today. Stereotypes die hard."

-

• "Library Journal" 15 Dec. 1966: 6214. [70 words]

-

• "New York Amsterdam News"

"31 Negroes in New Book." "New York Amsterdam News" 24 Sept. 1966: 45. "ProQuest". [brief notice of publication of the anthology]

"Publish Book of Negro Short Stories, Oct. 31." "New York Amsterdam News" 5 Nov. 1966: 14. "ProQuest". "Mr. Clarke, director of HARYOU-ACT's Heritage Teaching Program, has compiled the first anthology of Negro-written short stories ever published in the United States. . . . the book includes the work of 31 authors and, according to one reviewer, 'there is warmth, humor, tragedy and sadness in these stories, but surprisingly little bitterness or cynicism.'"

[*Note:* The claim that this is the first anthology of short stories by Negro authors is mistaken: apart from selections of short stories in comprehensive anthologies such as "The Negro Caravan" (1941) and "Anthology of American Negro Literature" (1944), there was also "Best Short Stories by Afro-American Writers, 1925-1950", ed. Nick Aaron Ford and H. L. Faggett (Boston: Meador, 1950). There is no overlap in the contents of the 1950 volume and Clarke's anthology—but six of the seven short stories in the "Anthology of American Negro Literature" are reproduced by Clarke, as well as one of the short stories that appears in "The Negro Caravan".]

-

• Rose, Jeanne. "What Negroes Remember." [Rev. of "American Negro Short Stories", ed. Clarke.] "The Sun" (Baltimore) 16 Oct. 1966: FE7. "ProQuest".

"For the white American who seriously wants to learn what makes his black fellow-citizens tick, it would be hard to imagine a better, or less violent primary text to recommend than this book. For, as the jacket indicates, these are in the main not bitter or even cynical stories; hopeful, resigned, realistic or indignant, their authors have tried to present black America as they see it—and their anthologizer, editor of "Freedomways" magazine, has produced an anthology that should be read.

"Not that every one of the 32 ["sic", actually 31] stories is a literary masterpiece. The earlier ones, by Paul Laurence Dunbar and Charles Waddell Chesnutt, date sadly in style, though this would be true in any similar retrospective collection. It is interesting, in fact, to watch the growth in literary skill as the writings move up through the decades.

"In the main these men and women speak proudly with their own voices, and very often from their childhood memories. Many of the stories, especially those laid in the South, are told by or through the eyes of a child, and in many others children bear important roles. Several stories, laid in schools, gain poignance from the authors' faith and hope that 'the new generation' will attain what their parents and teachers have vainly sought.

"Besides the rural South, the next most popular milieu in the volume is Harlem—especially the Harlem of the cats and the jazz bands. . . . But in the main the Southern stories hold more originality. Two writers have kept to the old legends—Chesnutt in 'The Goopherd Grapevine' and Arthur P. Davis with one really jolly tale, 'How John Boscoe Outsung the Devil.' Zora Neale Hurston tells movingly in 'The Gilded Six Bits' how a marriage in toruble was healed. Richard Wright's searing 'Bright and Morning Star,' Lerone Bennett's 'The Convert' and a surprising contribution by Frank Yerby emphasize the evil side of black-white relationships.

"The last story in the book, and probably the best, is Ernest J. Gaines's 'The Sky Is Gray,' which epitomizes in 26 pages, related again by a young boy, the tragedies, struggles and hopes of today's Southern Negro. Told flatly, unsentimentally, 'The Sky Is Gray' yet speaks proudly not for Negro nor against white man, but for humanity. Truly a noble story, it makes a fitting climax to an uneven but vital anthology."

-

• Ward, Francis. Rev. of "American Negro Short Stories", ed. Clarke. "Negro Digest" (Sept. 1967): 94-95. [Google Books preview]

"What better time to bring to the fore a collection of short stories by black writers? The political and social ferment of our times has created an unprecedented quest by black people for a true accounting of their past" (94).

"Clarke brings together the stories of 32 ["sic", actually 31] writers" (94). "In limiting each writer to one selection, the anthology leaves itself open to criticism by reducing the giants to the level of the ordinary. . . . More depth should be allowed, though, to men like Chestnutt ["sic"], Hughes and Wright, the major influences for lesser known writers" (95).

-

Google Books preview

-

Commentary on anthology

-

• "Clarke's introduction sketches the development of the genre beginning with Chesnutt and Dunbar. His selections [31 stories in total] include such classics as 'The Goopherd Grapevine,' 'The City of Refuge,' 'The Gilded Six Bits,' 'Bright and Morning Star,' and 'The Sky is Gray.' An appendix contains biographical notes. A revised and expanded edition appeared in 1993 as "Black American Short Stories" [see below]" (Kinnamon 1997: 472).

• "In the 1960s, interest in books by and about blacks boomed.• Arna Bontemps, a longtime and close friend of Langston Hughes, edited "American Negro Poetry" (1963) for us [Hill & Wang publishers]. Bontemps and Jack Conroy's "Anyplace But Here" (1966) was also on our list. John Henrik Clarke, who died in 1998, compiled "American Negro Short Stories" which we published in 1966. It was revised in the late 1990s and it has continued to be a very strong seller" (Arthur W. Wang, in "An Interview with Arthur W. Wang," by Robert Twombly. "Reviews in American History" 28.1 [2000]: 1-15, at 7).

• An example of this "boom" is discussed moments earlier in the interview: "From Plantation to Ghetto" (1966), by Augie Meier and Elliot Rudwick was "a highly acclaimed and successful book": "[Aïda] Donald knew Augie Meier's important work on black history and believed that he would write a first-class book. Someone suggested that we might be criticized for having a white man as author. Don't forget this was the 1960s! I answered the question with a very quiet 'Nonsense.' To my knowledge, there were no such complaints. When the manuscript was delivered, with Elliot Rudwick as co-author, we knew we had a winner. "From Plantation to Ghetto" (1966) went into a second and then a third edition, nineteen printings. Winners like this don't come often and they don't last forever; it will be supplanted on our list by a new volume early in the new millennium" ("Ibid".).

-

See also

-

• Clarke, John Henrik. "Transition in the American Negro Short Story." "Phylon" 21.4 (1960): 360-66. "JSTOR". [The introduction is actually a lightly revised version of Clarke's 1960 essay]

"After the emergence of Richard Wright the double standard for Negro writers was over. Hereafter Negro writers had to stand or fall by the same standards and judgments used to evaluate the work of white writers. The era of the patronized and pampered Negro writer had at last come to an end. The closing of this era may in the final analysis be the greatest contribution that Richard Wright has made to the status of Negro writers and to Negro literature" (365). [cf. Introduction, p. xviii]

• Clarke, John Henrik. "The Origin and Growth of Afro-American Literature: A Survey." "Negro Digest" (Dec. 1967): 54-67. [Google Books preview]

-

Google Books preview

-

• Weissinger, Thomas. "A Bibliography of John Henrik Clarke." "We're Not Going To Take It Anymore: Educational and Psychological Practices from an Africentric Paradigm of Helping". Ed. Gerald G. Jackson. Silver Spring, MD: Beckham Publications, 2005. 167-76. [Google Books preview] (There are also further tributes to Clarke in this volume, 96-117.)

-

Google Books preview

-

• Bibliography of works by and about John Henrik Clarke. Cornell University Libraries. Web.

-

Cornell University Libraries

-

• John Henrik Clarke Papers 1937-1996. Schomburg Center, New York Public Library. Web.

-

Schomburg Center, New York Public Library

-

Cited in

-

• Kinnamon 1997: 472.

-

Item Number

-

A0070

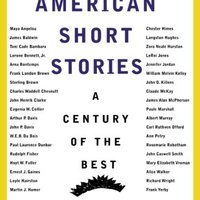

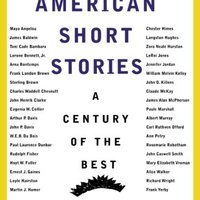

Black American Short Stories: One Hundred Years of the Best

Black American Short Stories: One Hundred Years of the Best

Black American Short Stories: One Hundred Years of the Best

Black American Short Stories: One Hundred Years of the Best