-

Title

-

Anthology of Verse by American Negroes

-

This edition

-

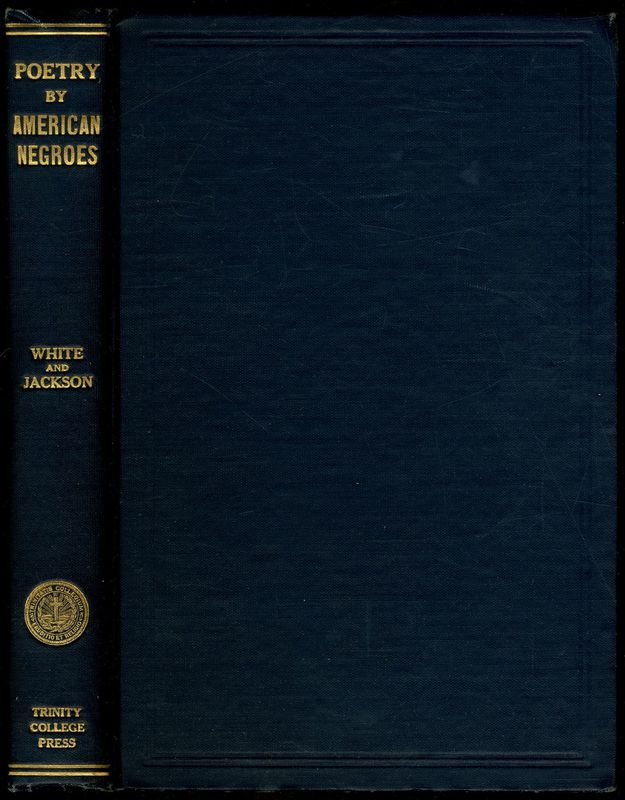

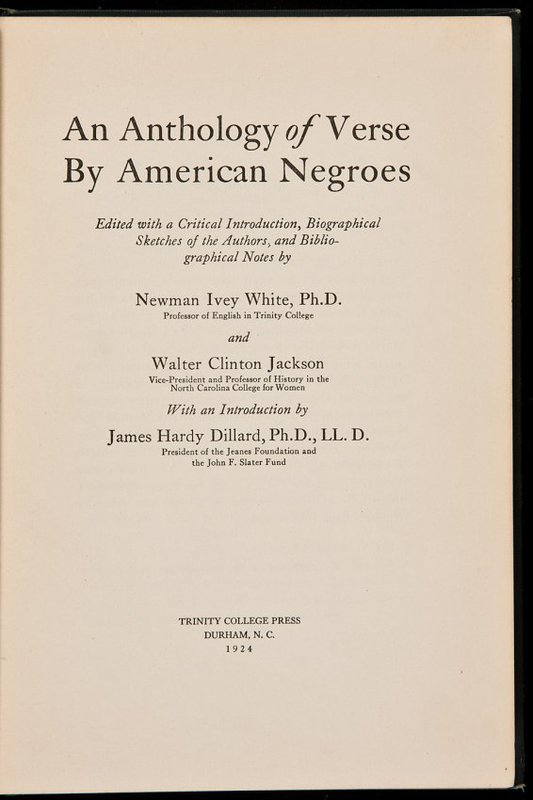

"An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes" . Ed. Newman Ivey White and Walter Clinton Jackson. Intro. James Hardy Dillard. Durham, NC: Trinity College P, 1924. xi+250 pp.

-

Other editions, reprints, and translations

-

• Repr. Moore Publishing Company, 1969.

-

Table of contents

-

[James Hardy Dillard] / Introductory Note (x)

[Newman Ivey White and Walter Clinton Jackson] / Introduction (1)

● Phillis Wheatley / On Imagination (28)

● Phillis Wheatley / To a Gentleman and Lady on the Death of the Lady's Brother, etc. (30)

● Phillis Wheatley / Liberty and Peace (31)

● George Moses Horton / Meditations on a Cold, Dark and Rainy Night (34)

● George Moses Horton / Praise of Creation (35)

● James Madison Bell / Song for the First of August (38)

● Frances Ellen Watkins Harper / The Slave Mother (41)

● Frances Ellen Watkins Harper / Bury Me in a Free Land (42)

● Charles L. Reason / Freedom (44)

● Alberry A. Whitman / To the Student (50)

● Alberry A. Whitman / Ye Bards of England (52)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Crisis (55)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Dreams (1) (56)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Dreams (2) (57)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / The End of the Chapter (57)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Ere Sleep Comes to Soothe the Weary Eyes (59)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / A Hymn (61)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Love Despoiled (61)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Love's Phases (62)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Warrior's Prayer (63)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Night (64)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Ode to Ethiopia (64)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Slow Through the Dark (66)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / By Rugged Ways (66)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Drizzle (67)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / A Banjo Song (68)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Deserted Plantation (71)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Angelina (72)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Expectation (74)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / A Frolic (75)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / How Lucy Backslid (76)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Possum (82)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Temptation (83)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / When Malindy Sings (85)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / A Choice (87)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Mortality (88)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Sum (88)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Life (89)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Poet and the Baby (89)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Life's Tragedy (90)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Compensation (90)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / A Death Song (91)

● George Marion McClellan / The Path of Dreams (92)

● George Marion McClellan / To Hollyhocks (94)

● George Marion McClellan / The Ephemera (95)

● George Marion McClellan / The Feet of Judas (96)

● George Marion McClellan / A Belated Oriole (97)

● Daniel Webster Davis / Night on the Ol' Plantashun (98)

● Daniel Webster Davis / Hog Meat (100)

● Daniel Webster Davis / Stickin' to de Hoe (101)

● Daniel Webster Davis / Pomp's Case Argued (103)

● George Hannibal Temple / Crispus Attucks (104)

● Charles R. Dinkins / Invocation (105)

● Charles R. Dinkins / We Are Black, but We Are Men (111)

● Charles R. Dinkins / "Thy Works Shall Praise Thee" (113)

● Timothy Thomas Fortune / We Know No More (115)

● Timothy Thomas Fortune / Lincoln (115)

● J. Mord Allen / The Psalm of the Uplift (116)

● J. Mord Allen / The Devil an' Sis' Viney (117)

● J. Mord Allen / When the Fish Begin to Bite (128)

● J. Mord Allen / Shine on, Mr. Sun (130)

● J. Mord Allen / Counting Out (131)

● Clara Ann Thompson / His Answer (133)

● Clara Ann Thompson / Mrs. Johnson Objects (133)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / A Little Song (135)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / By an Inland Lake (136)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / In a Grave-Yard (136)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / Song: To-Day and To-Morrow (137)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / From the Crowd (137)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / Song of a Syrian Lace Seller (138)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / A Song of Living (139)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / The Eternal Self (141)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / Golden Moonrise (142)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / Sic Vita (142)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / This Is My Life (143)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / Sandy Star (144)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / The Mystery (144)

● William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite / To the Sea (145)

● Joseph Seaman [sic] Cotter [Sr.] / The Negro's Educational Creed (147)

● Joseph Seaman [sic] Cotter [Sr.] / On a Proud Man (147)

● Joseph Seaman [sic] Cotter [Sr.] / Destiny (147)

● Walter Everette Hawkins / Wrong's Reward (148)

● Walter Everette Hawkins / A Spade Is Just a Spade (149)

● Walter Everette Hawkins / The Death of Justice (150)

● H. Cordelia Ray / Dawn's Carol (152)

● H. Cordelia Ray / Our Task (152)

● H. Cordelia Ray / The Triple Benison (153)

● Edward Smythe Jones / A Song of Thanks (154)

● Benjamin Griffith Brawley / The Plan (157)

● Benjamin Griffith Brawley / Chaucer (158)

● Benjamin Griffith Brawley / The Bells of Notre Dame (158)

● Benjamin Griffith Brawley / Ballade of One that Died before his Time (159)

● Fenton Johnson / Love's Good-Night (160)

● Fenton Johnson / Death of Love (161)

● Fenton Johnson / In the Evening (161)

● Fenton Johnson / When I Die (162)

● James David Corrothers / An Indignation Dinner (164)

● James David Corrothers / The Negro Singer (165)

● James David Corrothers / Paul Laurence Dunbar (166)

● James David Corrothers / The Dream and the Song (167)

● George Reginald Margetson / A Prayer (169)

● George Reginald Margetson / Time (169)

● George Reginald Margetson / Resurrection (170)

● James Weldon Johnson / Fifty Years (172)

● James Weldon Johnson / O Black and Unknown Bards (175)

● James Weldon Johnson / "Lazy" (177)

● James Weldon Johnson / Answer to Prayer (178)

● James Weldon Johnson / Mother Night (179)

● Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / The Goal (181)

● Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / Rain Music (181)

● Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / Sonnet to Negro Soldiers (182)

● Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / And What Shall You Say? (182)

● John Wesley Holloway / Discouraged (184)

● John Wesley Holloway / Plowin' Cane (185)

● John Wesley Holloway / Calling the Doctor (186)

● John Wesley Holloway / The Corn Song (187)

● Charles Bertram Johnson / A Rain Song (189)

● Charles Bertram Johnson / Old Things (190)

● Ray E. [sic] Dandridge / Days (191)

● Ray E. [sic] Dandridge / Tracin' Tales (192)

● Ray E. [sic] Dandridge / Zalka Peetruza (192)

● Jessie Redmond Fauset / Oriflamme (194)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / The Wings of Oppression (195)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / Tuskegee (196)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / Freedom (197)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / "So Quietly" (197)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / Self-Determination (198)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / To the Smartweed (199)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / Christmas at Melrose (200)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / The Symphony (202)

● Leslie Pinckney Hill / Spring (203)

● Claude McKay / The Easter Flower (204)

● Claude McKay / The Tropics in New York (204)

● Claude McKay / Harlem Shadows (205)

● Claude McKay / In Bondage (205)

● Claude McKay / The Lynching (206)

● Claude McKay / Baptism (206)

● Claude McKay / Absence (207)

● Georgia Douglas Johnson / Isolation (208)

● Georgia Douglas Johnson / The Octoroon (209)

● Georgia Douglas Johnson / Little Son (209)

● Georgia Douglas Johnson / Taps (209)

● Countee P. Cullen / The Touch (210)

● Sarah Collins Fernandis / A Vision (212)

Biographical and Critical Notes (214)

Index of Authors (238)

Index of Titles (239)

-

About the anthology

-

● Includes 144 poems by 34 African American poets, including several longer poems in their entirety.

● Provides a critical introduction to the volume as a whole and a bio-bibliographical headnote for each author, often brief but more extended for the authors about whom more information is available. Occasionally provides a contextualizing footnote to the poems (typically, drawing on the author's biography or the reception of their work). After the selections, there is a section of "Bibliographical and Critical Notes" (214-37, in small type), which offer critical commentary on 52 poets, plus discussion of Schomburg's "Biographical Checklist of American Negro Poetry" (1916) and Kerlin's anthology, "Negro Poets and Their Poems" (1923).

● Newman Ivey White (1892-1948) completed his graduate studies at Harvard and taught at Trinity College and then Duke University. "Lewis Patton, his friend and eulogist, says he stood for 'progressive movements not only at Duke but in wider educational and public movements as well.' In 1933 White organized the Duke Labor and Materials Exchange to supplement community relief. And he worked to get Norman Thomas on the 1932 ballot. 'He had the courage' says Patton, 'to espouse unpopular causes and a willingness to look authority in the eye' [Lewis Patton. "In Memoriam: Newman Ivey White, 1892-1948." "Duke University Library Bulletin" (July 1950): 11]" (Potter 1986: 277).

● White "had an amateur musician's fancy for black folksong. He published a long article on collecting folklore in 1916, and by 1920 he had a substantial data base of both song and poetry by black Americans" (Potter 1986: 278).

-

Anthology editor(s)' discourse

-

● "As southern white men who desire the most cordial relations between the races we hope this volume will help its white readers more clearly to understand the Negro's feelings on certain questions that must be settled by the coöperation of the two races. From the same point of view we hope that Negro readers, too accustomed, perhaps, to a debilitating literary patronage, will not misinterpret as unfriendly a critical attitude in which we have tried to supplant patronage with honest, unbiased appraisal" (a passage from the editors' introduction quoted at the head of Eric Walrond's review of the volume in "The New Republic" [10 Sept. 1924]: 52.)

-

● "Bibliographical and Critical Notes": "The following notes seek to give some idea of the nature, content, and value of most of the volumes used in the preparation of this book. They are condensed and edited from reading notes taken at the time the volumes were used. A few volumes were examined under conditions that made the taking of notes impracticable and are therefore not represented in this list; one or two others have been omitted either because they were fully treated in the essay with which this volume is prefaced or because, like the works of Paul Laurence Dunbar, they are easily accessible in any library. These notes are included in this volume because they contain information difficult to incorporate in a critical and historical preface and because they show, in a way that seemed otherwise impossible, the level from which the better poets of the Negro race have developed" (214).

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

• On 16 Sept. 1924, Newman I. White (one of the editors of the anthology) writes a note to the "Editors of "The Crisis", New York City," stating: "I have heard that "The Crisis" has reviewed "An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes", by White and Jackson, but no copy of the review has come in to the Trinity College Press. I am most anxious to know how the book is being received by the Negro publications and should appreciate it greatly if you would send me a copy of your review" (W. E. B. Du Bois Papers [MS 312] , Special Collections and University Archives, U of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries).

-

W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, U of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

-

• Du Bois, W. E. B. Rev. of "An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes," ed. Newman Ivey White and Walter Clinton Jackson. "The Crisis" 28.5 (Sept. 1924): 219.

"N. I. White and W. C. Jackson, professors in Trinity College, a Southern white institution of North Carolina, publish 'An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes.' It is a thoroughly sincere bit of work for which these men should have the thanks of the Negro race. The preface says: 'As Southern white men who desire the most cordial relations between the races we hope that this volume will help its white readers more clearly to understand the Negro's feelings on certain questions that must be settled by the cooperation of the two races. From the same point of view we hope that Negro readers, too accustomed, perhaps, to a debilitating literary patronage, will not misinterpret as unfriendly a critical attitude in which we have tried to supplant patronage with honest, unbiased appraisal.' The only difference between these selections and those of [James Weldon] Johnson ["The Book of American Negro Poetry"] and [Robert T.] Kerlin ["Negro Poets and Their Poems"] is perhaps somewhat greater emphasis upon many comparatively unknown Negro poets like Horton, Temple, Allen and others. There is a critical bibliography and excellent indexes." [full text]

-

Google Books

-

• Rev. of "An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes", ed. Newman Ivey White and Walter Clinton Jackson. "Journal of Negro History" 9.3 (1924): 371-73. "JSTOR".

This anthology is published by "Trinity College, one of the leading white institutions of learning in the South" (371). Newman Ivey White is professor of English at Trinity College and Walter Clinton Jackson is vice-president and professor of history at the North Carolina College for Women. James Hardy Hillard, author of the introduction, is president of the Jeanes Foundation and the John F. Slater Fund. "It is an event of no mean significance in the history of the Negro that these gentlemen representing the interests of [the] former master class thus concede that the race has achieved so much in freedom. Most students in our colleges, on the contrary, are taught that the Negro has not yet achieved anything worth-while and the race is accordingly eliminated from any consideration in discussing the achievements of mankind" (371).

"These authors, however, are very careful in giving their own race much credit for the development of this power of the Negro. White students are interested, they say, because the authors of these poems have achieved their capacity for this form of expression alongside of and in close association with their own people. One Negro has become a poet by contact with the whites; another reaches this end through financial aid and encouragements of public men of the white race. Exactly how poets can be produced in this way, however, is not made sufficiently clear" (371).

The reviewer states that the editors offer none too high estimates of "the various Negro poets":

--"Jupiter Hammon's products are called doggerel, simple and crude in rhyme and verse form, extremely limited in vocabulary, incoherent in though and without any of the subtler qualities that distinguish poetry from prose, although his poems are said to be respectable in motive and sentiment" (371);

--"Phillis Wheatley's poetry, like her character, is marked by a sincere and earnest religious sentiment. Thomas Jefferson was rather harsh in dismissing her work as 'beneath criticism.' Yet 'their claim to literary merit is certainly a very modest one, but the great respect // with which she has been addressed and referred to by subsequent Negro poets is by no means misplaced'" (371-72);

--"George M. Horton, noted for dogged persistence in the face of difficulties, had a strong sense of jingle and almost never went wrong on meter" (372);

--"Frances Ellen Watkins Harper's poems are clear and vigorous in thought, but are sometimes crude and violent and are without any real poetic grace" (372);

--"Charles L. Reason's "Freedom" is free from rant and has both dignity and depth. 'Whittier wrote worse anti-slavery stanzas than some of Reason's'" (372);

--"The poems of [Paul Laurence] Dunbar do not reveal any great depths of knowledge, but they are free from the crudities characteristic of uneducated or half-educated writers of verse. He is far above habitual technical errors; his expression is uniformly adequate to the thought and often superior to it. 'If after all he falls short of the perfect fitness of fiction that is called the "inevitable phrase" and gives some particular shade of thought its final adequate expression for all time, where else in American poetry, except for a few lines from Poe and still fewer from Emerson, is "the inevitable phrase" to be found?'" (372)

--"William Stanley Braithwaite, who stands next to Dunbar, 'has a superior "savoir faire" in handling literary background that is probably due to his longer and more intimate associations with books and writers. His poems have grace, but he is too idealistic for humor. He has a sense of human fate and the seriousness of life, but he falls short of the knowledge of life and the sympathetic interest in human types that Dunbar possessed'" (372).

"While this book in itself marks an epoch in the recognition of Negro achievements in this country, we cannot conclude that the literary productions of these poets have thereby been properly evaluated, especially so when one reads the following which is presented by the authors at the end of their introduction, as General Conclusions:

"'A general review of the history of Negro poetry makes two conclusions immediately obvious. One is that there has been decided and unmistakable progress, both in volume and quality. From Jupiter Hammon to William Stanley Braithwaite and Leslie Pinckney Hill is a far cry, as far as from the first anonymous slave to the colleges, insurance companies, banks, and business enterprises now operated by and for Negroes. The second conclusion is that the quality of the poetry has generally depended upon the cultural opportunities of the poet. Dunbar derived his love of poetry // from a mother who had acquired it from a more cultivated white mistress. He developed his poetry largely through the encouragement of cultivated men—men of another race, because his own race had few men capable of giving him the sympathetic assistance he needed. Braithwaite developed his poetry by similar contacts. Joseph Seaman Cotter had not a day of schooling before he was twenty; he wrote verses that naturally have their limitations but indicate that better verses would have resulted from a better opportunity. He gave his son, Joseph Seaman Cotter, Jr., some of the advantages he himself had missed, and before his early death the young man produced a volume of decided promise. A third conclusion might be added, namely, that Negro poets have not yet, as a class, risen to the levels of poetry attained by white poets far more richly endowed with leisure and cultural background. No Negro, justly proud of what the poets of his race have already achieved, should consider this fact a humiliation. New England produced no poetry superior to the poems of the best Negro poets of today until she had spent a century and a half in overcoming the wilderness and building up a community life in which there was leisure for indulging in poetry and capacity for appreciating it. England took three centuries after the Norman Conquest to produce her first great poet; the Negro has been hardly that long out of Africa. Nor need the Negro or the friend of the Negro feel unduly disturbed by the circumstance that so much Negro poetry is given over to defiance and protest. Socially this fact is worthy of serious consideration, but from the artistic side it is no more a permanent symptom than the era of bumptious national assertiveness that once characterized a section of American literature. It is simply a growing-pain. Braithwaite has already passed beyond it, and a wider cultural horizon for other Negroes will have the same results that it had for American literature. This wider horizon is coming inevitably. Already there are communities where the Negro is developing a real social system of his own. He is acquiring, more and more rapidly, both property and education. A race, unquestionably endowed with humor and music, that has made a marked advance in poetry within the scant sixty years of its freedom, will unquestionably produce finer poetry when conditions have followed their present tendency for a generation or two. In the light of these facts the present period is, from the larger point of view, likely to witness the real dawn of Negro poetry'" (372-73).

-

• "The Boston Transcript" 24 May 1924: 3. (520 words)

-

• Guiterman, Arthur. "Outlook" 137 (28 May 1924): 157. (110 words)

"The Introduction and the biographical and critical notes enhance the value of the book as a study of the rapidly increasing and developing literature of a race."

-

• Rev. of "Anthology of Verse by American Negroes." "The Nation" 118 (11 June 1924): 688. (a brief, one-paragraph notice; 50 words)

"A valuable collection covering about the same ground as that covered by Mr. Robert T Kerlin in his recent volume. Both books are interesting as evidence of the fact that the poetic energies of the Negro race are at present directed away from folk-rhymes to more ambitious and more serious if as yet less successful forms."

-

• "New York World" 15 June 1924: 7e. (200 words)

"This is a most creditable and appreciative volume."

-

• J. T. S. "Literary Review" (New York) 5 July 1924: 875. (300 words)

"This anthology selects from the entire field of American negro verse that which for various reasons, seems most worth preserving. It must be confessed that the bulk of the work seems solely of historical interest."

-

• Walrond, Eric. "A Negro Anthology." "The New Republic" 40 (10 Sept. 1924): 52-53.

"It is regrettable that this volume, 'ready for the press in 1921,' did not make its appearance then, for it is without doubt the best anthology of American Negro poetry that has yet appeared. Good as is Kerlin's book, this is much superior to it; it lacks that work's passionate academicianism. Putting it alongside the Johnson compilation the latter suffers visibly. Here, for the first time, is a genuinely critical estimate of Negro poetry. As indicated in the paragraph quoted [see above, under anthology editors' discourse], it does not pretend to grovel before its subject. Nor do its editors assume a lofty, unsympathetic attitude.

"To match Mr. Johnson's essay on the creative genius of the Negro there is an introduction of some twenty-six pages by Professor White which is the most brilliant, the most illuminating appraisal of Negro poetry. In it we find that 'Negro poets have not yet, as a class, risen to the levels of poetry attained by many white poets far more richly endowed with leisure and cultural background.' Professor White attributes this to (1) the lack of cultural opportunities of the poet ('Dunbar derived his love of poetry from a mother who had acquired it from a more cultivated white mistress') and (2) because his own race had few men capable of giving him the sympathetic assistance he needed."

"Making liberal use of Arthur Schomburg's Bibliographical Checklist of American Negro Poetry, Professors White and Jackson have exhumed, along with a few others, two poets the exclusion of either of whom would be a serious loss to any anthology of American Negro // poetry. They are Charles L. Reason and J. Mord Allen. Reason's Freedom, a poem of 168 lines, is 'the best antebellum Negro poem extant.' Professor White tells us that 'Whittier wrote worse anti-slavery stanzas than some of the black poet's.' Though a poet of slight stature, Allen possesses 'a central and sober sanity in his poetry that reveals an intellectual poise equalled by very few other Negro writers. He is not too race-sensitive to expose and laugh at the professional agitator. His poems show a humorous and tolerant observance of human nature and a narrative ability hardly inferior to the same traits in Dunbar.' Of course we find in this essay also the absurd discovery that there is a 'jaded bitterness' in the poems of Claude McKay and that 'some of his poems are too erotic for good taste and conventional morality.'"

"Including selections from T. Thomas Fortune to Countee P. Cullen, it is bulwarked with a bibliography that is at once exhaustive and stimulating. Then, in addition, there is about it the flavor--the desire, burning and impassioned,--to be fair and square to these black bards, to overlook their race and judge their work according to the universally accepted standards of literature."

-

• Lewis, Theophilus. "The Messenger" (Oct. 1926). Repr. in "Voices of a Black Nation: Political Journalism in the Harlem Renaissance," ed. Theodore G. Vincent. San Francisco: Ramparts Press, 1973. 332-35.

"A refreshing an instructive book on the subject of Aframerican poetry is Poetry by American Negroes, an anthology compiled by Professor Newman Ivey White and Professor Walter Clinton Jackson, of Trinity College and the North Carolina College for Women, respectively. I take it for granted that both professors are southerners and up to the time of the appearance of their book eligible for membership in the Ku Klux Klan. Still, both the compassionate patronizing of the old line Southerner and the sickening cant and kudos of the current Stallingses and Van Vechtens are agreeably absent from their book. The authors neither profess a profound love for Negro poetry because they had black wet nurses nor intimate that because Claude McKay is capable of weaving an intricate rhyme scheme he is peer to Dante Alighieri and John the Baptist to a renaissance of Negro art.

"Instead they discuss their subject in the sober manner of men with a sound understanding of the mechanics of English verse, a catholic knowledge of its variety and development and an abiding appreciation of its beauty. From this point of view they con the entire output of Aframerican bards from Phyllis Wheatly to Georgia Douglas Johnson. Their method is to submit samples of a poet's representative work together with a brief biographical sketch and a critical remark or two. Their book represents not only a prodigious amount of research, but also a faculty for detective work rarely possessed by literary men; for much of their material was to be found only in out of print periodicals and pamphlets nobody but the publisher himself ever saw.

"The anthology includes samples of the work of six poets before Dunbar, with Phyllis Wheatly heading the list. Excepting the work of Phyllis Wheatly, none of the verses submitted can be called poetry except by courtesy. This, of course, is to be expected, for it is the work of writers who began to function before the illiterate bards of the cotton field and cane brake had adequately fertilized racial thought. All of these poets were simply verse writers toying with primitive ideas. As these jejune ideas were culled from books, mainly European history, they were quite innocent of any distinctive Negro flavor. Dunbar was first to plow under the thin layer of tinsel ideas into the feelings of the people; hence he was the first Aframerican to produce mature poetry. Since his time the poets of the race have gone deeper and deeper into the realm of feeling with the result that we now have a body of poetry as distinctively Aframerican as the spirituals . . ."

-

• Schroeder, Andreas. "Where Editors Fear Offending Negroes." "The Province" 27 June 1969: 48.

Reviewing the 1969 reprint of this anthology, Schroeder argues that "a more paranoid trio of editors [i.e. White and Jackson, the two editors of "An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes" and R. B. Shuman, editor of "Nine Black Poets" (1968), which was published at the same time] you could hardly find. Desperately afraid of offending their Negro readers, yet conscious of their role as critical editors . . . they fall back repeatedly into an empty, non-committal commentary or a carefully tolerant, bordering on the patronizing, attitude." Schroeder says White and Jackson's anthology, through its selection of poems, is "a little like an attempt to make black poetry white"; but, at the same time, Schroeder objects to the division of literature into "black" and "white" camps, saying that it is "not differentiated by colors" (as quoted in "Wikipedia").

-

Wikipedia (entry on this anthology)

-

Commentary on anthology

-

• "The emphasis of the critical commentary by White and Jackson in this compilation and in subsequent articles on the literature of the Negro is on the element of race feeling which they see as the outstanding characteristic of the Negro writer. White elaborates his views of race feeling in Negro poetry in his discussion published in the "South Atlantic Quarterly", and he points out that his reader—meaning, of course, his white reader—can gain a deeper understanding of the attitudes, the hopes, the aspirations of the American Negro through a reading of the products of the creative genius of the Negro writer. For him the [Negro] author is an official spokesman for his race, sometimes apologetic, but more often militant and aggressive in the demands which he makes for his people in the name of American democracy. White does not altogether approve of the race consciousness which he finds in the writings of Negro authors, but he recognizes that these are altogether legitimate inclusions in the literature of America" (John S. Lash. "The Anthologist and the Negro Author." "Phylon" 8.1 [1947]: 68-76, at 72).

-

• "An anthology of black American poets from Phillis Wheatley to Countee Cullen and Sarah Collins Fernandis, with bio-bibliographical sketches before the poems of each poet" (Rowell 1972: 59).

-

• Potter, Vilma R. "Race and Poetry: Two Anthologies of the Twenties." "CLA Journal" 29.3 (1986): 276-87.

-

• The editors describe themselves as "Southern white men who desire the most cordial relations between the races" and propose "honest, unbiased appraisal" rather than "uncritical patronage," arguing that "at least a few Negroes have demonstrated undeniable ability in poetry" (quoted in Kinnamon 1997: 469).

-

See also

-

• White, Newman Ivey. "Racial Traits in Negro Song." "Sewanee Review" 28 (July 1920): [398].

-

• White, Newman Ivey. "American Negro Poetry." "South Atlantic Quarterly" 20.4 (Oct. 1921): 304-22.

-

Google Books

-

• White, Newman Ivey. "Race Feeling in Negro Poetry." "South Atlantic Quarterly" 21 (Jan. 1922): 19-29.

-

• White, Newman Ivey, ed. "American Negro Folk-Songs" (1928).

-

American Negro Folk-Songs

American Negro Folk-Songs

-

Cited in

-

• Jahn 1965: 217 (no. 2215).

• Kinnamon 1997: 469

-

Item Number

-

A0014

American Negro Folk-Songs

American Negro Folk-Songs

Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Supplement to the Study of American Literature; repr. as Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Anthology of Negro Poetry

Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Supplement to the Study of American Literature; repr. as Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Anthology of Negro Poetry