-

Title

-

Book of American Negro Poetry

-

This edition

-

"The Book of American Negro Poetry" . Ed. with an essay on the Negro's Creative Genius by James Weldon Johnson. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1922. xlviii+217 pp.; rev. ed. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1931. vii+300 pp.

-

Online access

-

• 1922 edition (copy from Brigham Young U): available at Internet Archive:

-

Internet Archive

-

• A second copy (from Library of Congress) of the 1922 edition is also available at Internet Archive: (this copy is missing p. 183, "Sonnet" by Alice Dunbar Nelson)

-

Internet Archive

-

• A copy of the 1922 edition (U of Michigan): available at Google Books

-

Google Books

-

• A copy of the 1922 edition (Harvard U): available at HathiTrust

-

HathiTrust

-

Transcribed version of the 1922 text is available online at Bartleby.com:

-

Bartleby.com

-

Table of contents

-

(1922 ed.): the Appendix, Biographical Index of Authors, and Index of Titles are not listed in the Table of Contents, but have been included here:

• [James Weldon Johnson] / Preface

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / A Negro Love Song

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / Little Brown Baby

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / Ships That Pass in the Night

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / Lover's Lane

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Debt

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Haunted Oak

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / When de Co'n Pone's Hot

• Paul Laurence Dunbar / A Death Song

• James Edwin Campbell / Negro Serenade

• James Edwin Campbell / De Cunjah Man

• James Edwin Campbell / Uncle Eph's Banjo Song

• James Edwin Campbell / Ol' Doc' Hyar

• James Edwin Campbell / When Ol' Sis' Judy Pray

• James Edwin Campbell / Compensation

• James D. Corrothers / At the Closed Gate of Justice

• James D. Corrothers / Paul Laurence Dunbar

• James D. Corrothers / The Negro Singer

• James D. Corrothers / The Road to the Bow

• James D. Corrothers / In the Matter of Two Men

• James D. Corrothers / An Indignation Dinner

• James D. Corrothers / Dream and the Song

• Daniel Webster Davis / 'Weh Down Souf

• Daniel Webster Davis / Hog Meat

• William H. A. Moore / Dusk Song

• William H. A. Moore / It Was Not Fate

• W. E. Burghardt Du Bois / A Litany of Atlanta

• George Marion McClellan / Dogwood Blossoms

• George Marion McClellan / A Butterfly in Church

• George Marion McClellan / The Hills of Sewanee

• George Marion McClellan / The Feet of Judas

• William Stanley Braithwaite / Sandy Star and Willie Gee: I. Sculptured Worship, II. Laughing It Out, III. The Exit, IV. The Way, V. Onus Probandi

• William Stanley Braithwaite / Del Cascar

• William Stanley Braithwaite / Turn Me to My Yellow Leaves

• William Stanley Braithwaite / Ironic: LL.D.

• William Stanley Braithwaite / Scintilla

• William Stanley Braithwaite / Sic Vita

• William Stanley Braithwaite / Rhapsody

• George Reginald Margetson / Stanzas from The Fledgling Bard and the Poetry Society

• James Weldon Johnson / O Black and Unknown Bards

• James Weldon Johnson / Sence You Went Away

• James Weldon Johnson / The Creation

• James Weldon Johnson / The White Witch

• James Weldon Johnson / Mother Night

• James Weldon Johnson / O Southland

• James Weldon Johnson / Brothers

• James Weldon Johnson / Fifty Years

• John Wesley Holloway / Miss Melerlee

• John Wesley Holloway / Calling the Doctor

• John Wesley Holloway / The Corn Song

• John Wesley Holloway / Black Mammies

• Leslie Pinckney Hill / Tuskegee

• Leslie Pinckney Hill / Christmas at Melrose

• Leslie Pinckney Hill / Summer Magic

• Leslie Pinckney Hill / The Teacher

• Edward Smyth Jones / A Song of Thanks

• Ray G. Dandridge / Time to Die

• Ray G. Dandridge / 'Ittle Touzle Head

• Ray G. Dandridge / Zalka Peetruza

• Ray G. Dandridge / Sprin' Fevah

• Ray G. Dandridge / De Drum Majah

• Fenton Johnson / Children of the Sun

• Fenton Johnson / The New Day

• Fenton Johnson / Tired

• Fenton Johnson / The Banjo Player

• Fenton Johnson / The Scarlet Woman

• R. Nathaniel Dett / The Rubinstein Staccato Etude

• Georgia Douglas Johnson / The Heart of a Woman

• Georgia Douglas Johnson / Youth

• Georgia Douglas Johnson / Lost Illusions

• Georgia Douglas Johnson / I Want to Die While You Love Me

• Georgia Douglas Johnson / Welt

• Georgia Douglas Johnson / My Little Dreams

• Claude McKay / The Lynching

• Claude McKay / If We Must Die

• Claude McKay / To the White Fiends

• Claude McKay / The Harlem Dancer

• Claude McKay / Harlem Shadows

• Claude McKay / After the Winter

• Claude McKay / Spring in New Hampshire

• Claude McKay / The Tired Worker

• Claude McKay / The Barrier

• Claude McKay / To O. E. A.

• Claude McKay / Flame-Heart

• Claude McKay / Two-an'-Six

• Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / A Prayer

• Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / And What Shall You Say?

• Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / Is It Because I Am Black?

• Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / The Band of Gideon

• Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / Rain Music

• Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. / Supplication

• Roscoe C. Jamison / The Negro Soldiers

• Jessie Fauset / La Vie C'est la Vie

• Jessie Fauset / Christmas Eve in France

• Jessie Fauset / Dead Fires

• Jessie Fauset / Oriflamme

• Jessie Fauset / Oblivion

• Anne Spencer / Before the Feast of Shushan

• Anne Spencer / At the Carnival

• Anne Spencer / The Wife-Woman

• Anne Spencer / Translation

• Anne Spencer / Dunbar

• Alex Rogers / Why Adam Sinned

• Alex Rogers / The Rain Song

• Waverley Turner Carmichael / Keep Me, Jesus, Keep Me

• Waverley Turner Carmichael / Winter Is Coming

• Alice Dunbar-Nelson / Sonnet

• Charles Bertram Johnson / A Little Cabin

• Charles Bertram Johnson / Negro Poets

• Otto Leland Bohanan / The Dawn's Awake

• Otto Leland Bohanan / The Washer-Woman

• Theodore Henry Shackelford / The Big Bell in Zion

• Lucian B. Watkins / Star of Ethiopia

• Lucian B. Watkins / Two Points of View

• Lucian B. Watkins / To Our Friends

• Benjamin Brawley / My Hero

• Benjamin Brawley / Chaucer

• Joshua Henry Jones, Jr. / To a Skull

Appendix:

• Plácido / Despida a mi madre (En la capilla)

• Plácido / Farewell to My Mother (In the chapel), trans. William Cullen Bryant

• Plácido / Plácido's Farewell to His Mother (Written in the chapel of the Hospital de Santa Cristina on the night before his execution), trans. James Weldon Johnson

Biographical Index of Authors (209-14)

Index of Titles (215-17)

-

About the anthology

-

• The anthology includes 117 poems by 31 authors. Johnson's Preface is dated "New York City, 1921" (xlviii).

-

• Johnson's introduction offers an important critical discussion of poetry by American Negroes (or "Aframericans" of the United States, as he sometimes writes). Johnson discusses the Negro spirituals (especially their musical accomplishments); he offers a somewhat unsympathetic assessment of Phillis Wheatley's poetry (even while arguing that she has not received her due from critics of American literature); he lauds the achievement of Paul Laurence Dunbar (whom Johnson knew personally); he discusses the comparative literary achievements of Negro writers in Europe and in Latin America (and why the achievements of Negro American poets have not risen to the same level of eminence); he discusses the status of poetry written in Negro dialect (which made Dunbar's reputation but which is being put aside by contemporary Negro poets, both because of its limitation to the two notes of humor and pathos and because it speaks for the picturesque rustic Negro, but not for the new and growing urban Negro communities).

-

• In his introductory essay, Johnson indicates that he initially conceived of this anthology as a sampling of verse by contemporary writers only, with no pretensions to being comprehensive nor with any extended critical introduction: "I first planned to select twenty-five to thirty poems which I judged to be up to a certain standard, and offer them with a few words of introduction and without comment" (xlvii); "but, perhaps because this is the first collection of its kind, I realized the absence of a starting-point and was led to provide one and to fill in with historical data what I felt to be a gap" (xxxix). As a result, the anthology as it stands includes 117 poems by 31 authors: "In the collection, as it grew to be, that 'certain standard' has been broadened if not lowered; but I believe that this is offset by the advantage of the wider range given the reader and the student of the subject" (xlvii).

-

• Johnson thanks "Mr. Arthur A. Schomburg, who placed his valuable collection of books by Negro authors at my disposal" (xlvii).

-

• The contents included in the anthology were previously published (or will appear in forthcoming volumes) from Dodd, Mead (for Dunbar); from Cornhill Publishing (for Georgia Douglas Johnson; Joseph S. Cotter, Jr.; Bertram Johnson; and Waverley Carmichael); from Neale & Co. (for John W. Holloway); and from William Braithwaite's privately printed "Sandy Star and Willie Gee" (then forthcoming)--or in the following periodicals: "The Crisis", "The Century Magazine", "The Liberator", "The Freeman", "The Independent", "Others", and "Poetry: A Magazine of Verse" (xlvii-xlviii).

-

Anthology editor(s)' discourse

-

• "There is, perhaps, a better excuse for giving an Anthology of American Negro Poetry to the public than can be offered for many of the anthologies that have recently been issued. The public, generally speaking, does not know that there are American Negro poets--to supply this lack of information is, alone, a work worthy of somebody's effort.

"Moreover, the matter of Negro poets and the production of literature by the colored people in this country . . . . is a matter which has a direct bearing on the most vital of American problems.

"A people may become great through many means, but there is only one measure by which its greatness is recognized and acknowledged. The final measure of the greatness of all peoples is the amount and standard of the literature and art they have produced. The world does not know that a people is great until that people produces great literature and art. No people that has produced great literature and art has ever been looked upon by the world as distinctly inferior"

"The status of the Negro in the United States is more a question of national mental attitude toward the race than of actual conditions. And nothing will do more to change that mental attitude and raise his status than a demonstration of intellectual parity by the Negro through the production of literature and art" (vii).

-

• "Is there likelihood that the American Negro will be able to do this? . . . [Indeed, but] I make here what may appear to be a more startling statement by saying that the Negro has already proved the possession of these powers by being the creator of the only things artistic that have yet sprung from American soil and been universally acknowledged as distinctive American products" (viii)--namely, (1) the Uncle Remus tales (folktales), (2) the "spirituals" or slave songs (folk songs), (3) cakewalking (and American dance more generally), and (4) Ragtime (and blues) (music)(viii-xv).

-

• "Now, these dances which I have referred to and Ragtime music may be lower forms of art, but they are evidence of a power that will some day be applied to the higher forms" (xv).

-

• "In the 'spirituals,' or slave songs, the Negro has given America not only its only folksongs, but a mass of noble music. I never think of this music but that I am struck by the wonder, the miracle of its production. How did the men who originated these songs manage to do it? The sentiments are easily accounted for; they are, for the most part, taken from the Bible. But the melodies, where did they come from? . . . It is to be noted that whereas the chief characteristic of Ragtime is rhythm, the chief characteristic of the 'spirituals' is melody" (xv-xvi). "Naturally, not as much can be said for the words of these songs as for the music. Most of the songs are religious. Some of them are songs expressing faith and endurance and a longing for freedom. In the religious songs, the sentiments and often the entire lines are taken bodily from the Bible. However, there is no doubt that some of these religious songs have a meaning apart from the Biblical text" (xvii). "The bulk of the lines to these songs, as is the case in all communal music, is made up of choral iteration and incremental repetition of the leader's lines. If the words are read, this constant iteration and repetition are found to be tiresome; and it must be admitted that the lines themselves are often very trite. And, yet, there is frequently revealed a flash of real, primitive poetry" (xvii). "Regarding the line, 'I lay in de grave an' stretch out my arms,' Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson of Boston, one of the first to give these slave songs serious study, said: 'Never it seems to me, since man first lived and suffered, was his infinite longing for peace uttered more plaintively than in that line'" (xviii).

-

• "These Negro folksongs constitute a vast mine of material that has been neglected almost absolutely. . . . But there is a great hope for the development of this music, and that hope is the Negro himself. A worthy beginning has already been made by Burleigh, Cook, Johnson, and Dett. And there will yet come great Negro // composers who will take this music and voice through it not only the soul of their race, but the soul of America. And does it not seem odd that this greatest gift of the Negro has been the most neglected of all he possesses? Money and effort have been expended upon his development in every direction except this. This gift has been regarded as a kind of side show, something for occasional exhibition; wherein it is the touchstone, it is the magic thing, it is that by which the Negro can bridge all chasms. No persons, however hostile, can listen to Negroes singing this wonderful music without having their hostility melted down" (xviii-xix).

-

• "This power of the Negro to suck up the national spirit from the soil and create something artistic and original, which, at the same time, possesses the note of universal appeal, is due to a remarkable racial gift of adaptability; it is more than adaptability, it is a transfusive quality. And the Negro has exercised this transfusive quality not only here in America, where the race lives in large numbers, but in European countries, where the number has been almost infinitesimal. Is it not curious to know that the greatest poet of Russia is Alexander Pushkin, a man of African descent; that the greatest romancer of France is Alexander Dumas, a man of African descent; and that one of the greatest musicians of England is Coleridge-Taylor, a man of African descent?" (xix).

-

• "I know the question naturally arises: If out of the few Negroes who have lived in France there came a Dumas; and out of the few Negroes who have lived in England there came a Coleridge-Taylor; and if from the man who was at the time, probably, the only Negro in Russia there sprang that country's national poet, why have not the millions of Negroes in the United States with all the emotional and artistic endowment claimed for them produced a Dumas, or a Coleridge-Taylor, or a Pushkin?

"The question seems difficult, but there is an answer. The Negro in the United States is consuming all of his intellectual energy in this gruelling race-struggle. And the same statement may be made in a general way about the white South. Why does not the white South produce // literature and art? The white South, too, is consuming all of its intellectual energy in this lamentable conflict. Nearly all of the mental efforts of the white South run through one narrow channel. The life of every Southern white man and all of his activities are impassably limited by the ever-present Negro problem. And that is why, as Mr. H. L. Mencken puts it, in all that vast region, with its thirty or forthy million poeple and its territory as large as a half a dozen Frances or Germanys, there is not a single poet, not a serious historian, not a creditable composer, not a critic good or bad, not a dramatist dead or alive" (xx-xxi).

-

• "But, even so, the American Negro has accomplished something in pure literature. The list of those who have done so would be surprising both by its length and the excellence of the achievements. One of the great books written in this country since the Civil War is the work of a colored man, 'The Souls of Black Folk,' by W. E. B. Du Bois" (xxi).

-

• The catalog of literary achievement begins with Jupiter Hammon (xxv) and, more emphatically, with Phillis Wheatley, who arrived in 1761 in Boston, in the cargo of a slave ship as "a little girl of seven or eight years of age" (xxi). She was purchased by John Wheatley, "a wealthy gentleman of Boston, . . . as a servant for his wife. Mrs. Wheatley was a benevolent woman. She noticed the girl's quick mind and determined to give her opportunity for its development. Twelve years later Phillis published a volume of poems" (xxi).

"Phillis Wheatley has never been given her rightful place in American literature. By some sort of conspiracy she is kept out of most of the books, especially the text-books on literature used in the schools. Of course, she is not a 'great' American poet--and in her day there were no great American poets--but she is an important American poet. Her importance, if for no other reason, rests on the fact that, save one, she is the first in order of time of all the women poets of America. And she is among the first of all American poets to issue a volume" (xxii). Compares Wheatley's poetry to: the verse of Urian Oakes, President of Harvard, who published a "crude and lengthy elegy" in 1667 (and "which is quoted from in most of the books on American literature"); the versified translations in the 'Bay Psalm Book' (1640); and to Anne Bradstreet, who published her volume of poetry, 'The Tenth Muse', in 1750 ("a little over twenty years" before Wheatley's volume): "We do not think the black woman suffers much by comparison with the white. Thomas Jefferson said of Phillis: 'Religion has produced a Phillis Wheatley, but it could not produce a poet; her poems are beneath contempt.' It is quite likely that Jefferson's criticism was directed more against religion than against Phillis' poetry. On // the other hand, George Washington wrote her with his own hand a letter in which he thanked her for a poem which she had dedicated to him. He, later, received her with marked courtesy at his camp at Cambridge" (xxiii-xxiv).

"Phillis Wheatley's poetry is the poetry of the Eighteenth Century. She wrote when Pope and Gray were supreme; it is easy to see that Pope was her model. Had she come under the influence of Wordsworth, Byron or Keats or Shelley, she would have done greater work. As it is, her work must not be judged by the work and standards of a later day, but by the work and standard of her own day and her own contemporaries. By this method of criticism she stands out as one of the important characters in the making of American literature, without any allowances for her sex or her antecedents" (xxiv).

-

• "According to 'A Bibliographical Checklist of American Negro Poetry,' compiled by Mr. Arthur A. Schomburg, more than one hundred Negroes in the United States have published volumes of poetry ranging from pamphlets to books of from one hundred to three hundred pages. About thirty of these writers fill in the // gap between Phillis Wheatley and Paul Laurence Dunbar" (xxiv-xxv). "The poets between Phillis Wheatley and Dunbar must be considered more in the light of what they attempted than of what they accomplished. . . . And yet there are several names that deserve mention. George M. Horton, Frances E. Harper, James M. Bell and Alberry A. Whitman, all merit consideration when due allowances are made for their limitations in education, training and general culture" (xxv). "The poetry of both Mrs. Harper and of Whitman had a large degree of popularity; one of Mrs. Harper's books went through more than twenty editions" (xxvi).

-

• "It is curious and interesting to trace the growth of individuality and race consciousness in this group of poets" (xxvii).

"Jupiter Hammon's verses were almost entirely religious exhortations" (xxvii).

"Only very seldom does Phillis Wheatley sound a native note. Four times in single lines she refers to herself as 'Afric's muse.' In a poem of admonition addressed to the students at the 'University of Cambridge in New England' she refers to herself as follows: 'Ye blooming plants of human race divine, / An Ethiop tells you 'tis your greatest foe.' But one looks in vain for some outburst or even complaint against the bondage of her people, for some agonizing cry about her native land. In two poems she refers definitely to Africa as her home, but in each instance there seems to be under the sentiment of the lines a feeling of almost smug contentment at her own escape // therefrom" (xxvii-xxviii): see "On Being Brought from Africa to America" and the poem addressed to the Earl of Dartmouth (xxviii). Johnson accuses Wheatley of being unfeeling in the very lines in which she accuses the slave traders who snatched her from her parents in Africa of being unfeeling: "In the poem addressed to the Earl of Dartmouth, she speaks of freedom and makes a reference to the parents from whom she was taken as a child, a reference which cannot but strike the reader as rather unimpassioned: '. . . What pangs excruciating must molest, / What sorrows labor in my parents' breast? / Steel'd was that soul and by no misery mov'd / That from a father seiz'd his babe belov'd; / Such, such my case. And can I then but pray / Others may never feel tyrannic sway?'" (xxviii). [We might note, in passing, how Wheatley's inverted syntax places an emphasis on the word "belov'd" that anticipates the focus that Toni Morrison would bring to that same term.] Johnson continues: "The bulk of Phillis Wheatley's work consists of poems addressed to people of prominence. . . . . // Indeed, it is apparent that Phillis was far from being a democrat. . . . unless a religious meaning is given to the closing lines of her ode to General Washington, she was a decided royalist: 'A crown, a mansion, and throne that shine / With gold unfading, Washington! be thine'" (xxviii-xxix). "What Phillis Wheatley failed to achieve is due in no small degree to her education and environment. Her mind was steeped in the classics; her verses are filled with classical and mythological allusions. She knew Ovid thoroughly and was familiar with other Latin authors. She must have known Alexander Pope by heart. And, too, she was reared and sheltered in a wealthy and cultured family,--a wealthy and cultured Boston family; she never had the opportunity to learn life; she never found out her own true relation to life and to her surroundings. And it should not be forgotten that she was only about thirty years old when she died. The impulsion or the compulsion that might have driven her genius off the worn paths, out on a journey of exploration, Phillis Wheatley never received. But, whatever her limitations, she merits more than America has accorded her" (xxx).

George M. Horton "was born a slave in North Carolina in 1797" (xxv) and he "expressed in all of his poetry strong complaint at his condition of slavery and a deep longing for freedom" (xxx).

"In Mrs. [Frances E.] Harper we find something more than the complaint and the longing of Horton. We find an expression of a sense of wrong and injustice" (xxxi).

"Whitman, in the midst of 'The Rape of Florida,' a poem in which he related the taking of the State of Florida from the Seminoles, stops and discusses the race question. He discusses it in many other poems; and he discusses it from many different angles. In Whitman we find not only an expression of a sense of wrong and // injustice, but we hear a note of faith and a note also of defiance" (xxxi-xxxii).

-

• "Paul Laurence Dunbar stands out as the first poet from the Negro race in the United States to show a combined mastery over poetic material and poetic technique, to reveal innate literary distinction in what he wrote, and to maintain a high level of performance. He was the first to rise to a height from which he could take a perspective view of his own race. He was the first to see objectively its humor, its superstitions, its shortcomings; the first to feel sympathetically its heart-wounds, its yearnings, its aspirations, and to voice them all in a purely literary form" (xxxiii).

"Dunbar's fame rests chiefly on his poems in Negro dialect. This appraisal of him is, no doubt, fair; for in these dialect poems he not only carried his art to the highest point of perfection, but he made a contribution to American literature unlike what any one else had made, a contribution which, perhaps, no one else could have made. Of course, Negro dialect poetry was written before Dunbar wrote, most of it by white writers; but the fact stands out that Dunbar was the first to use it as a medium for the true interpretation of Negro character and psychology. And, yet, dialect poetry does not // constitute the whole or even the bulk of Dunbar's work. . . . Indeed, Dunbar did not begin his career as a writer of dialect"--but he turned to it because, as he often said to Johnson at the time, "I've got to write dialect poetry; it's the only way I can get them to listen to me" (xxxiii-xxxiv).

"My personal friendship with Paul Dunbar began before he had achieved recognition, and continued to be close until his death. . . . I was with Dunbar at the beginning of what proved to be his last illness. He said to me then: 'I have not grown. I am writing the same things I wrote ten years ago, and am writing them no better.' His self-accusation was not fully true; he had grown, and he had gained a surer control of his art, but he had not accomplished the greater things of which he was constantly dreaming; the public had held him to the things for which it had accorded him recognition. If Dunbar had lived he would have achieved some of those dreams, but even while he talked // so dejectedly to me he seemed to feel that he was not to live. He died when he was only thirty-three" (xxxv).

"It has a bearing on this entire subject to note that Dunbar was of unmixed Negro blood; so, as the greatest figure in literature which the colored race in the United States has produced, he stands as an example at once refuting and confounding those who wish to believe that whatever extraordinary ability an Aframerican shows is due to an admixture of white blood" (xxxv).

"To whom may he be compared, this boy who scribbled his early verses while he ran an elevator, whose youth was a battle against poverty, and who, in spite of almost insurmountable obstacles, rose to success? A comparison between him and Burns is not unfitting. The similarity between many phases of their lives is remarkable, and their works are not incommensurable. Burns took the strong dialect of his people and made it classic; Dunbar took the humble speech of his people and in it wrought music" (xxxv).

-

• "Mention of Dunbar brings up for consideration the fact that, although he is the most outstanding figure in literature among the Aframericans of the United States, he does not stand alone among the Aframericans of the whole Western world. There are Plácido and Manzano in Cuba; Vieux and Durand in Haiti, Machado de Assis in Brazil; Leon Laviaux in Martinique, and others still that might be mentioned, who stand on a plane with or even above Dunbar. Plácido and Machado de Assis rank as great in the literatures of their respective countries without any qualifications whatever. They are world figures in the literature of the Latin languages" (xxxvi).

Plácido's famous sonnet, "Mother, Farewell," was written during "the few hours preceding his execution" by the Spanish authorities in 1844, along with ten others, on account of his commitment for the "struggle for Cuban independence": "Plácido's sonnet to his mother has been translated into every important language; William Cullen Bryant did it in English" but "Bryant's translation totally misses the intimate sense of the delicate subtility of the poem" (xxxvii): "Plácido's sonnet and two English versions will be found in the Appendix" (xxxviii, note).

-

• "In considering the Aframerican poets of the Latin languages I am impelled to think that, as up to this time the colored poets of greater universality have come out of the Latin-American countries rather than out of the United States, they will continue to do so for a good many years. The reason for this I hinted at in the first part of this preface. The colored poet in the United States labors within limitations which he cannot easily pass over. He is always on the defensive or the offensive. The pressure upon him to be propagandistic is well nigh irresistible. These conditions are suffocating to breadth and to real art in poetry. In addition he labors under the handicap of finding culture not entirely colorless in // the United States. On the other hand, the colored poet of Latin-America can voice the national spirit without any reservations. And he will be rewarded without any reservations, whether it be to place him among the great or declare him the greatest. So I think it probable that the first world-acknowledged Aframerican poet will come out of Latin-America. Over against this probability, of course, is the great advantage possessed by the colored poet in the United States of writing in the world-conquering English language" (xxxviii-xxxix).

-

• "It may be surprising to many to see how little of the poetry being written by Negro poets to-day is being written in Negro dialect. The newer Negro poets show a tendency to discard dialect; much of the subject-matter which went into the making of traditional dialect poetry, 'possums, watermelons, etc., they have discarded altogether, at least, as poetic material. This tendency will, no doubt, be regretted by the majority of white readers; and, indeed, it would be a distinct loss if the American // Negro poets threw away this quaint and musical folk-speech as a medium of expression. And yet, after all, these poets are working through a problem not realized by the reader, and, perhaps, by many of these poets themselves not realized consciously. They are trying to break away from, not Negro dialect itself, but the limitations on Negro dialect imposed by the fixing effects of long convention" (xxxix-xl).

-

• The stereotyped picture of the "Negro in the United States" is that of "a happy-go-lucky, singing, shuffling, banjo-picking being or as a more or less pathetic figure. The picture of him is in a log cabin amid fields of cotton or along the levees. Negro dialect is naturally and by long association the exact instrument for voicing this phase of Negro life; and by that very exactness it is an instrument with but two full stops, humor and pathos. So even when he confines himself to purely racial themes, the Aframerican poet realizes that there are phases of Negro life in the United States [e.g., life in Harlem] which cannot be treated in the dialect either adequately or artistically" (xl).

-

• "What the colored poet in the United States needs to do is something like what Synge did for the Irish; he needs // to find a form that will express the racial spirit by symbols from within rather than by symbols from without, such as the mere mutilation of English spelling and pronunciation. He needs a form that is freer and larger than dialect, but which will still hold the racial flavor; a form expressing the imagery, the idioms, the peculiar turns of thought, and the distinctive humor and pathos, too, of the Negro, but which will also be capable of voicing the deepest and highest emotions and aspirations, and allow of the widest range of subjects and the widest scope of treatment" (xl-xli).

-

• "Negro dialect is at present a medium that is not capable of giving expression to the varied conditions of Negro life in America, and much less is it capable of giving the fullest interpretation of Negro character and psychology. This is no indictment against the dialect as dialect, but against the convention in which Negro dialect in the United States has been set. In time these conventions may become lost, and the colored poet in the United States may sit down to write in dialect without feeling that his first line will put the general reader in a frame of mind which demands that the poem be humorous or pathetic. In the meantime, there is no reason why these poets should not continue to do the beautiful things that can be done, and done best, in the dialect" (xli).

-

• "In stating the need for Aframerican poets in the United States to work out a new and distinctive form of expression I do not wish to be understood to hold any theory that they should limit themselves to Negro poetry, to racial themes; the sooner they are able to write 'American' poetry spontaneously, the better. Nevertheless, I believe that the richest contribution the Negro poet can make to the American literature of the future will be the fusion into it of his own individual artistic gifts" (xli-xlii).

-

• The last part of Johnson's preface previews some of the poets featured in the anthology and offers some critical commentary on them:

--William Stanley Braithwaite, who is "unique among all the Aframerican writers the United States has yet produced" in that "He has gained his place, taking as the standard and measure for his work the identical standard and measure applied to American writers and American literature. He has asked for no allowances or rewards, either directly or indirectly, on account of his race. . . . But his place in American literature is due more to his work as a critic and anthologist than to his work as a poet" (xlii);

--W. E. B. Du Bois and Benjamin Brawley are better known for their nonfictional prose writings than for their poetry (xlii-xliii);

--Claude McKay, "although still quite a young man, has already demonstrated his power, breadth and skill as a poet . . . Mr. McKay gives evidence that he has passed beyond the danger which threatens many of the new Negro poets--the danger of allowing the purely polemical phases of the race problem to choke their sense of artistry" (xliii); Johnson includes also one of McKay's poems "written in the West Indian Negro dialect" "not only to illustrate the widest range of the poet's talent and to offer a comparison between the American and the West Indian dialects, but on account of intrinsic worth of the poem itself" (xliii-xliv);

--Fenton Johnson, "a young poet of the ultra-modern school who gives promise of greater work than he has yet done" (xliv);

--Jessie Fauset, who "possesses the lyric gift" and "works with care and finish" (xliv);

--Georgia Douglas Johnson, "a poet neither afraid nor ashamed of her emotions . . . The principal theme of Mrs. Johnson's poems is the secret dread down in every woman's heart, the dread of the passing of youth and beauty, and with them love" (xliv);

--Anne Spencer: "Of the half dozen or so of colored women writing creditable verse, Anne Spencer is the most modern and least obvious in her methods" (xliv);

--John W. Holloway, "more than any Negro poet writing in the dialect to-day, summons to his work the lilt, the spontaneity and charm of which Dunbar was the supreme master whenever he employed that medium" (xlv);

--James Edwin Campbell, also writes dialect verse (indeed, he was a precursor of Dunbar in doing so): "An error that confuses many persons in reading or understanding Negro dialect is the idea that it is uniform": But "A comparison of [Campbell's] idioms and phonetics with those of Dunbar reveals great differences. Dunbar is a shade or two more sophisticated and his phonetics approach nearer to a mean standard of the dialects spoken in the different sections. Campbell is more primitive and his phonetics are those of the dialect as spoken by the Negroes of the sea islands off the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia, which to this day remains comparatively close to its African roots, and is strikingly similar to the speech of the uneducated Negroes of the West Indies" (xlv);

--Daniel Webster Davis, "wrote dialect poetry at the time when Dunbar was writing. He gained great popularity, but it did not spread beyond his own race. Davis had unctuous humor, but he was crude" (xlvi);

--R. C. Jamison, "was barely thirty at the time of his death," but his "The Negro Soldiers" "is a poem with the race problem as its theme, yet it transcends the limits of race and rises to a spiritual height that makes it one of the noblest poems of the Great War" (xlvi);

--Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. "died a mere boy of twenty, and the latter part of that brief period he passed in an invalid state. Some months before his death he published a thin volume of verses which were for the most part written on a sick bed. In this little volume Cotter showed fine poetic sense and a free and bold mastery over his material" (xlvi).

-

• "I offer this collection without making apology or asking allowance. I feel confident that the reader will find not only an earnest for the future, but actual achievement. The reader cannot but be impressed by the distance already covered. It is a long way from the plaints of George Horton to the invectives of Claude McKay, from the obviousness of Frances Harper to the complexness of Anne Spencer. Much ground has been covered, but more will yet be covered. It is this side of prophecy to declare that the undeniable creative genius of the Negro is destined to make a distinctive and valuable contribution to American poetry" (xlvii).

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

• Untermeyer, Louis. "The Negro as Artist." "New York Tribune" 9 April 1922: 7.

-

Chronicling America (Library of Congress)

-

"If they are right--the prophets who predict the eventual submersion of the white race in a 'rising tide of color'--this decade may come to be known as the first black renaissance. Even without the perspective of time, we can see how curiously the generation has been influenced by the dark strain. African sculpture has made a powerful impress on the art of our day. American music reflects, in an increasing strength, the savage insistence of Congo drum beats, as well as the syncopated poignance of our Southern spirituals. In sociology the negro has begun to be his own interpreter. W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, editor of 'The Crisis,' has made two important contributions to the psychology of the suppressed race in 'The Souls of Black Folk' and 'Darkwater.' Benjamin Brawley, author of that excellent handbook, 'A Short History of the English Drama,' has done splendid pioneer's work with his 'The Negro in Art' and 'A Social History of the American Negro.'

"In literature the field is more uneven. In 'belles lettres', criticism and purely creative work the negro seems to suffer from an inhibition that prevents him from expressing his own emotions. Instead of giving free rein to a vision sharply differentiated from that of his white compatriots, he is content to ape their gestures, their inflections--too anxious to imitate with a stammering compliance their own imitations. Instead of being proudly race conscious, he is too often merely self-conscious.

"A Harlem Freud may some day rise to explain this quality in terms of mass repression; the negro as artist suffers, he may conclude, from a race inferiority complex. The implications of such an analysis are too deep and far-reaching for an article as superficial as this. They would, however, find repercussions in a recently published collection of poems chosen and edited by James Weldon Johnson, himself a poet, as was proved by his original volume, 'Fifty Years.'

"'The Book of Negro Poetry' [sic] is a record of the successes as well as the failures of the American negro (or, as Mr. Johnson prefers to call him, the Aframerican) as poet. Here are lyrics as native, as genuinely emotional, as 'A Death Song' and 'Little Brown Baby,' by Paul Laurence Dunbar, and here, also, are verses as maudlin and imitative as 'Ships That Pass in the Night' by the same writer. Here are rhapsodies as passionate as 'A Litany of Atlanta,' by W. E. B. Du Bois, and quatrains as cryptic as the obviously Robinsonian echoes of that ardent anthologist, William Stanley Braithwaite. Fenton Johnson adopts, without hesitation or apology, Masters's Spoon River idiom, but his angry intensity is his own.

"The outstanding discoveries of this collection are two, and they are less familiar even to their own race. They are Claude McKay and Anne Spencer. McKay does not disguise either himself or his poetry; his lines are saturated with a people's passion; they are colored with a mixture of bitterness and beauty. McKay's quieter and idyllic moments are less noteworthy; his muse is more characteristic when she is rebellious than resigned. This singer does not mistake polemics for poetry; he knows how to evoke a power of communication without shouting at the top of his voice. 'The Lynching' proves this. So does the impulsive sonnet, 'To the White Fiends,' and this significant outcry written during the recent race riots:

If We Must Die

If we must die--let it not be like hogs,

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursed lot.

If we must die--oh, let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain, then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

Oh, kinsmen! We must meet the common foe;

Though far outnumbered, let us still be brave,

And, for their thousand blows, deal one death blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we'll face the murderous cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but--fighting back!

"Anne Spencer's work sounds the other extreme of the gamut. Her verse is remarkably restrained, closely woven, intellectually complex. 'The Wife-Woman' and 'Translation' are steeped in a philosophy that has metaphysical overtones. But there is a racial opulence, an almost barbaric heat in the color of her lines.

"The names of Alex Rogers, J. W. Johnson and Paul Dunbar--all of whom wrote well known lyrics for popular songs like 'Lover's Lane,' 'Nobody' and 'The Jonah Man'--recall the negro composers who promised so much and who have performed so little. Will Marion Cook, one of the ablest musicians ever produced in America, startle us with the amazing 'Rain Song,' originally written for a Williams and Walker show.

"H. T. Burleigh is another negro composer who apparently has been ruined by the conservatories. W. C. Handy must be given credit for an entire tendency which originated with his 'Memphis Blues.' What has happened to him? Or to Rosamond Johnson, most adroit of ragtime adapters? Or to Nathaniel Dett, whose 'Listen to de Lambs' is one of the most eloquent pieces of choral writing ever scored by an American? Is the answer to be found, in spite of the negro's bursts of enthusiasm and gusto in his lack of sustained effort? In a sheer inability to cope with the strain of continued creative effort?

"In short, is this almost equal alternation of achievement and failure a physical or a psychical thing? This collection poses such questions even though it does not pretend to supply the answers. What it does supply is a full sized portrait of the American negro's contribution to a definitely American art. It shows that if the Aframerican has not yet had his renaissance, his poetry has at least passed its pains of parturition. It is no discredit to him that, with two exceptions, the most balanced and cumulative contribution to this compilation is Mr. Johnson's forty-page preface. It is a mark of which any group could allow itself to be proud." [full text of review]

-

• B. L. "Survey Midmonthly" 48 (15 April 1922): 89. (520 words)

"Few if any anthologies of modern American verse excel the one before us in the qualities that make for permanent value. Not everything in Mr. Johnson's collection is of equal merit; but no apology is needed on the ground of the social and educational status of the poets included in recommending this as a noteworthy volume. The one uniting character of these poems is their sincerity and, if one may say so, their inevitability. Dilettantism has no place in them; nor erudite search for the methods of old masters nor conscious search for eccentricity."

-

• Guiterman, Arthur. "The Independent" 108 (22 April 1922): 396. (220 words)

"Interesting and valuable as the collection is, the actual poetical value of its contents is rather disappointing. It will indeed be interesting to compare this first anthology in its field with another made, say, ten years from now."

-

• Fauset, Jessie. "As to Books." "The Crisis" 24.2 (June 1922): 66.

"One of the poets whom James Weldon Johnson quotes in his 'Book of American Negro Poetry,' himself defines unconsciously the significance of this collection. This poet, Charles Bertram Johnson, after noting in the development of Negro Poets 'the greater growing reach of larger latent power', declares:

'We wait our Lyric Seer,

By whom our wills are caught.

Who makes our cause and wrong

The motif of his song;

Who sings our racial good,

Bestows us honor's place,

The cosmic brotherhood

Of genius--not of race.'

"Not all of the 32 poets quoted here give evidence of this cosmic quality, but there is a fair showing, notably Mrs. Georgia Douglas Johnson whose power however is checked by the narrowness of her medium of expression, Claude McKay and Anne Spencer. Of Claude McKay I shall speak later [reviewing his volume "Harlem Shadows"], but I wonder why we have not heard more of Anne Spencer. Her art and its expression are true and fine; she blends a delicate mysticism with a diamond clearness of exposition, and her subject matter is original.

"This anthology itself has the value of an arrow pointing the direction of Negro genius, but the author's preface has a more immediate worth. It is not only a graceful bit of expository writing befitting a collection of poetry, but it affords a splendid compendium of the Negro's artistic contributions to America. Mr. Johnson feels that the Negro is the author of the only distinctively American artistic products. He lists his gifts as follows: Folk-tales such as we find in the Joel Chandler Harris collection; the Spirituals; the Cakewalk and Ragtime. What is still more important is the possession on the part of the Negro of what Mr. Johnson calls a 'transformative quality', that is the ability to adopt [sic] the original spirit of his milieu into something 'artistic and original, which yet possesses the note of universal appeal'" (66). [full text of review of this volume]

-

• "The Nation" 114 (7 June 1922): 694.

"Mr. Johnson's book has its chief value---and this is said, in no disparagement of the work of the poets he notes---in an admirable and well-written preface of some forty pages on The Creative Genius of the American Negro. In this he establishes in a manner that has not been done before the rightful place which the Negro occupies in American literature, and his contributions in folk-songs, ragtime, and folk-dances."

-

• Wood, Clement. "Literary Review" (New York) 10 June 1922: 716. (720 words)

"The critical attitude is arresting, and founded on rock. The historical matter is fresh, interesting, persuasive."

-

• "Monthly Bulletin" 20 (June 1922): 125.

-

• "Monthly Bulletin of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh" 27 (June 1922): 291.

-

• Littell, Robert. "Negro Poets." "The New Republic" (12 July 1922): 196.

"If it were possible to read Mr. Johnson's collection without knowing that all of it was written by Negroes, it is rather unlikely that one would think it remarkable in any way. One would be struck, here and there, by a certain simplicity, or technical competence, or musically flowing rhythm, or warmth of feeling, or occasional vivid phrase. Longer than any of these things, which are to be found in fairly good poetry anywhere, one would remember flashes of an aching indissoluble bitterness, a white anger stripped of all merely personal unhappiness, which, if one did not know by what oppressed it was uttered and against what oppressor, would be puzzling and disquieting. But since it is known who wrote them, it is impossible to read these poems as one reads most poetry. There arises at once, from the auction block and cotton field and lynching post and Harlem slum, the faces of our dark step-children, whom we have mistreated and misunderstood, whose time of trouble is not yet over, who are struggling painfully out of darkness toward some degree of happiness in an alien land" (196).

"They have their own fields to plough, which are not ours. The only music native to America is theirs . . . Is poetry one of their fields? Impossible to say as yet. On the strength of this collection by Negroes--nearly all now living--it is clear that they can write poetry as good as the great mass of ours, and they have produced one real poet, though by no means a great one--Mr. Claude McKay. It is an uneven collection. Too much of it is in the tradition of echoes, flowery phrase and emotion vaguely expressed which have always afflicted poetry. Too much of it is modelled after what is least worth copying. A good deal of it is in dialect, which always leaves me uneasy. Print cools and distorts phrases which, when spoken or sung, have a charming spontaneous gusto. Mr. Du Bois' A Litany at Atlanta is impressive, but as poetry is buttered too thick with indignation. Mr. Braithwaite's Sunday Star stirs pleasantly, like a light wind. Miss Spencer has great mastery over dreamy, half-mystical melodies. Mr. Fenton Johnson has a fine gift for direct observation and biting phrase in short prose poems whose reality makes him perhaps the most original contributor to the collection, though Mr. Claude McKay is by far the ablest poet" (196).

"If Mr. McKay and the other poets don't stir us unusually when they travel over poetic roads so many others have travelled before them, they make us sit up and take notice when they write about their race and ours. They strike hard, and pierce deep. It is not a merely poetic emotion that they express, but something fierce, and constant, and icy cold, and white hot. We quite believe Mr. Johnson when he says that 'the Negro in the United States is consuming all of his energy in this gruelling race struggle.' For it is the common thread running all through the book. It ranges from the restraint of Mr. Corrothers: 'To be a Negro in a day like this demands rare patience--patience that can wait in utter darkness'; through Mr. Johnson's own bitter lines: 'Lessons in degradation, taught and learned, / The memories of cruel sights and deeds, / The pent-up bitterness, the unspent hate, / Filtered through fifteen generations. . . .' to Mr. McKay's bitterness (in To the White Fiends), who when he writes 'Think you I could not arm me with a gun / And shoot down ten of you for every one / Of my black brothers murdered, burnt by you?' is only speaking for thousands of his race who feel the same hatred--hatred which boils over once in a while, as we know, but breaks in ineffectual waves on the stony white shore, and turns to something like the bottomless despair, felt by Mr. Fenton Johnson: 'I am tired of work; I am tired of building up somebody else's civilization, . . . / Throw the children into the river; civilization has given us too many. It is better to die than it is to grow up and find that you are colored'" (196).

-

• "The Bookman" (New York) 55 (July 1922): 530. (440 words)

"Aside from the excellence of much of the verse, the most striking thing, even to the casual reader, is the versatility of these writers."

-

• G. E. H. "Commission on the Church and Social Service. Information Service" (July 1922): 10. (240 words)

"A unique collection of literature among the many anthologies that have been issued. Its contents show a performance of a high order of excellence and give a prophecy of larger things in literature from the Negro of America as he gets greater opportunity to exercise what the author calls in his admirable introduction, the 'transfusive quality' of his genius."

-

• "Wilson Bulletin" 18 (July 1922): 182.

-

• "The Dial" 73 (Aug. 1922): 236. (70 words)

-

• "Journal of Negro History" 8.3 (July 1923): 347-48.

"A review of a book of poetry is out of place in an historical magazine unless, like the volume before us, it has an historical significance. It cannot be gainsaid that the poetry of a race passing through the ordeal of slavery, and later struggling for social and political recognition, must constitute a long chapter in its history. In fact, one can easily study the development of the mind of a thinking class from epoch to epoch by reading and appreciating its verse. It is fortunate that Mr. James Weldon Johnson has thus given the public this opportunity to study a representative number of the talented tenth of the Negro race.

"The poems themselves do not concern us here to the extent of showing in detail their bearing on the history of the Negro. The student of history, however, will find much valuable information in the interesting preface of the author covering the first forty-seven pages of the volume. The biographical index of authors in the appendix, moreover, presents in a condensed form sketches of the lives of thirty-one useful and all but famous members of the Negro race. Much of this information about those who have not been in the public eye a long time is entirely new, appearing here in print for the first time.

"The aim of the author is to show the greatness of the Negro as measured by his literature and art. He believes that the status of the Negro in the United States is more a question of national mental attitude toward the race than of actual conditions. 'And nothing,' says he, 'will do more to change that mental attitude and raise his status than a demonstration of intellectual parity by the Negro through the production of literature and art.'

"In the effort to show 'the emotional endowment, the originality and artistic conception and power of creating' possessed by the Negro, the author has begun with the Uncle Remus stories, the spirituals, the dance, the folks songs and syncopated music. He then presents the achievements of the Negro in pure literature, mentioning the works of Jupiter Hammon, George M. Horton, Frances E. Harper, James M. Bell and Albery A. Whitman. A large portion of this introduction given to the early writers is given to a discussion of Dunbar. He then introduces a number of poets of our own day, whose works constitute the verse herein presented. Among these are William Stanley Braithwaite, Claude McKay, Fenton Johnson, Jessie Fauset, Georgia Douglass Johnson, Annie Spencer, John W. Holloway, James Edwin Campbell, Daniel Webster Davis, R. C. Jamison, James S. Cotter, Jr., Alex Rogers, James D. Carrothers, Leslie Pinckney Hill, and W. E. B. DuBois." [full text of review]

-

Commentary on anthology

-

• Use of this anthology in Negro colleges and universities is mentioned in Thomas L. Dabney's "The Study of the Negro" ("Journal of Negro History" 19.3 [1934], 285).

• William Stanley Braithwaite. "Cavalcade of American Poetry." Rev. of "A History of American Poetry 1900-1940", by Horace Gregory and Matya Zaturenska. "Phylon" 8.2 (1947): 194-98. "JSTOR": Braithwaite notes that there is a chapter devoted to "The Negro Poet in America" in Gregory and Zaturenska's book: "Apparently the authors have their information of these poets from two anthologies, James W. Johnson's "The Book of American Negro Poetry", and Countee Cullen's "Caroling Dusk". Nothing new is said about Dunbar, who is presented with liberal quotations from Mr. Howells and Johnson. There is expressed an insight, but scarcely more than that, into Claude McKay's unfulfilled powers, and a summary with some strictures on Langston Hughes and a much too inadequate reference to Countee Cullen and Sterling Brown. To say, as they do, that James W. Johnson is the 'only American Negro poet of the twentieth century who achieved poetic maturity,' is to speak loosely. The young poets of the so-called Negro Renaissance of 1922 made Johnson over as a poet, and with the "Anthology of American Negro Poetry", which I gave him to do, laid the bases for his literary reputation. The most popular and successful of Johnson's books of poems, "God's Trombones", is the least original for, like the Uncle Remus stories of Joel Chandler Harris, these are but transcriptions of a speech and imagery that needed no creation. No mention whatever is made of Jean Toomer's haunting moods or of Anne Spencer, whose sensibility and imagination should take precedence over the declamatory verses of Margaret Walker, or the slender delicacy of // Jessie Fauset's few and brief lyrics which are recognized" (197-98).

Braithwaite's comments are directed at Horace Gregory and Matya Zaturenska's "A History of American Poetry 1900-1940" (1946), rather than at Johnson's "The Book of American Negro Poetry", but he does state that he (Braithwaite) suggested the project of this anthology to Johnson and he discusses the role of this anthology in consolidating Johnson's literary reputation.

• John S. Lash 1947: "Johnson's anthology is a milestone in the progress of the Negro author for several reasons. It performed the task which its editor had envisioned for it in his preface, for it was successful in calling attention to the best work of the poets included. Johnson's essay on the creative powers of the Negro established several critical platitudes which have since become standard commentaries on the literature of the Negro: his explanation of the limitations of Negro dialect in Dunbar and other poets has been echoed by many other critics, including Braithwaite and Redding; his differentiation between 'Afra-American literature' on the one hand and 'American literature' on the other has come to be accepted as fact; his appeal for a truly 'racial' literature has been taken up by many succeeding critics. But perhaps the greatest service which Johnson's essay and anthology performed for the Negro author was their establishment and demonstration of a theory of 'Negro literature' which, in view of the the outburst of expression immediately following, was fructifyied and extended. The definite phrases of Johnson's essay have become the titles of numerous articles on the literature of the Negro" (John S. Lash. "The Anthologist and the Negro Author." "Phylon" 8.1 [1947]: 68-76, at 71).

• "The 1922 edition contains a list of bio-bibliographical sketches (pp. 209-214) of the poets in the anthology . . . The preface is a brief history of black American poetry, from the oral tradition to Anne Spencer and Claude McKay" (Rowell 1972: 57).

• "The editorial mission Johnson set for himself was to prove that African Americans were capable of high art, for it was his belief that 'no people that has produced great literature and art has ever been looked upon by the world as distinctly inferior.' Today this view seems a bit tenderminded and not wholly appropriate in the context of hardcore American racism. In any event, no anthologist since has felt the need to make the case for a Black poetry anthology on quite the same grounds." (Keith Gilyard. "Spirit & Flame: An Anthology of Contemporary African American Poetry." Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1997. xx)

• This anthology "has been more influential than any other collection in // establishing the African-American poetic canon. [Johnson's] long preface is an exposition and defense of black cultural achievement, including ragtime and the spirituals as well as poetry, for in his view 'the final measure of the greatness of all peoples is the amount and standard of the literature and art they have produced'" (Kinnamon 1997: 468-69). "Johnson's long preface tolls the knell for dialect poetry" (Kinnamon 1997: 469). "The collection itself begins with such poets as Dunbar, James Edwin Campbell, and Daniel Webster Davis . . . In the second edition Johnson adds to the collection ample selections from the work of the best of the younger poets: Cullen, Hughes, Bennett, Brown, Bontemps, Helene Johnson. In both prefaces and headnotes (the headnote on Johnson himself is written by Sterling Brown), Johnson demonstrates a sure taste and a judicious temperament. The Book of American Negro Poetry is a classic anthology" (Kinnamon 1997: 468).

-

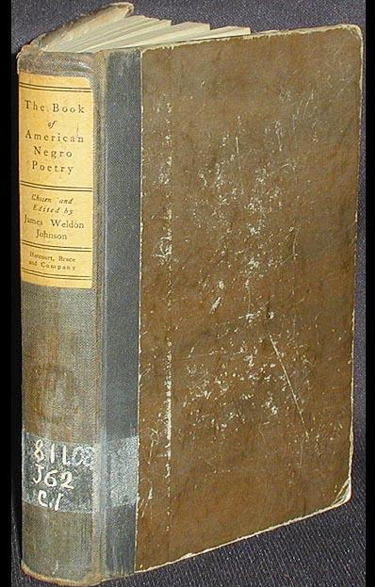

Advertising a used copy of the 1922 edition for sale, Classic Books and Ephemera (of Lansdowne, PA) describes the particular copy as follows:

"xlviii, 217 p.; 20 cm. Original black cloth spine with printed paper spine label; dark brown paper over boards. Old call number in white at tail of spine. Front fixed endpaper bears bookplate of the Blue Ridge Association Library; accession number in ink on title page and faint blue stamp of the library at foot of title page. Back endpapers contain circulation pocket and date due sheet indicating that the book circulated from 1931 to 1942. The Blue Ridge Association for Christian Conference and Training (the conference center of the YMCA of the Southern States), was established in 1906 at Black Mountain, N.C. With: a newspaper clipping from 1938 about the death of the editor, James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938), in a car/train accident. Johnson and his brother wrote many popular songs, including "Lift Every Voice and Sing", and performed in vaudeville as the Johnson Brothers. After serving as American consul in Venezuela and Nicaragua, he wrote and edited books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, including God's Trombones. He played a significant role in the Harlem Renaissance by promoting the work of black American writers in this book and others. Contains 177 poems by 31 poets, including Paul Laurence Dunbar, W.E.B. Du Bois, Claude McKay, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Leslie Pinckney Hill, the composer R. Nathaniel Dett, and the editor, James Weldeon Johnson. Includes short biographical note on each author. In Good+ Condition: cover is rubbed but original printed spine label is intact; shadow left by the newspaper clipping on the front endpapers; ex-library, as described above; back hinge weak; occasional pencil or ink marginal notations” (from Abe Books; item no longer available on site). [See image of this copy in images attached to this entry.]

-

See also

-

• Brown, Sterling A. "Outline for the Study of the Poetry of American Negroes". New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1931. 52 unnumbered pages. (Prepared to be used with "The Book of American Negro Poetry", edited by James Weldon Johnson; "this outline lists sources on the spiritual, secular folksongs and ballads, Brown also lists sources for the study of the black poets represented in Johnson's anthology. Pages 51-52: a list of poems on black people by white poets" [Rowell 1972: 55-56].)

• "James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871?-- June 26, 1938) was an American author, politician, critic, journalist, poet, anthologist, educator, lawyer, songwriter, early civil rights activist, and prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson is best remembered for his writing, which includes novels, poems, and collections of folklore. He was also one of the first African-American professors at New York University. Later in life he was a Professor of Creative Literature and Writing at Fisk University. During his six-year stay in South America he completed his most famous book The Autobiography" (WorldCat)

-

Cited in

-

• Lash 1946: 723.

• Kinnamon 1997: 468-69.

• Indexed in "The Columbia Granger's Index to African-American Poetry" (1999)

-

Item Number

-

A0011a

The Book of American Negro Poetry (rev. ed.)

The Book of American Negro Poetry (rev. ed.)

Afro-American Women Writers, 1746-1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide

Afro-American Women Writers, 1746-1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide The Book of American Negro Poetry (rev. ed.)

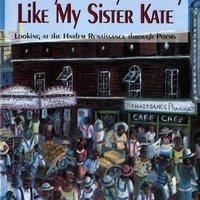

The Book of American Negro Poetry (rev. ed.) Shimmy Shimmy Shimmy Like My Sister Kate: Looking at the Harlem Renaissance through Poems

Shimmy Shimmy Shimmy Like My Sister Kate: Looking at the Harlem Renaissance through Poems Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Supplement to the Study of American Literature; repr. as Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Anthology of Negro Poetry

Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Supplement to the Study of American Literature; repr. as Singers in the Dawn: A Brief Anthology of Negro Poetry