-

Title

-

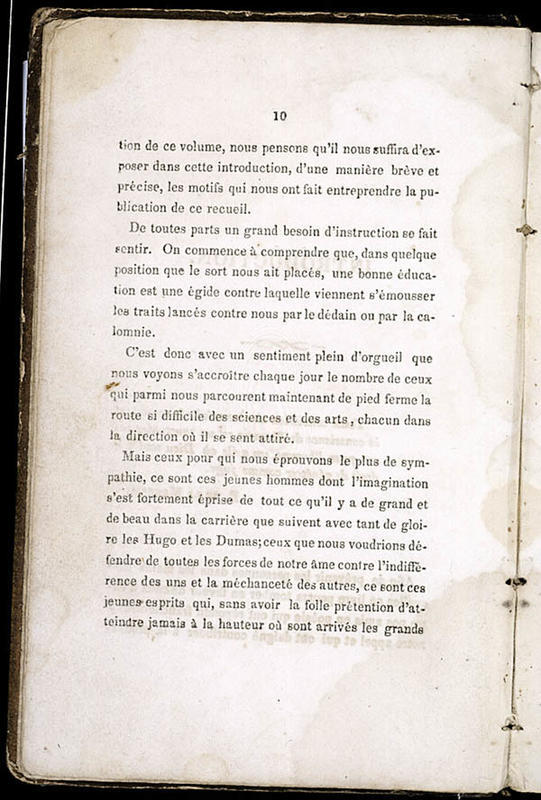

Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes

-

This edition

-

"Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes". Ed. Armand Lanusse. La Nouvelle-Orléans: H. Lauve, 1845. 215 pp.

-

Other editions, reprints, and translations

-

• Repr. Ed. Edward Maceo Coleman. Foreword H. Carrington Lancaster. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1945.

• Rev. as "Creole Voices: Poems in French by Free Men of Color, First Published in 1845". Ed. Edward Maceo Coleman. Foreword H. Carrington Lancaster. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1945. xlvi+130 pp.

(A "reworking of his edition of "Les Cenelles" with the addition of two new poets, V. A. (for V. E., i.e., Victor Ernest) Rillieux . . . and P. A. Desdunes" [Brosman 2013: 208].)

• Repr. as "Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes". Nendeln, Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1971. 215 pp.

• Repr. as "Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes". Ed. Mia D. Reamer. Shreveport, LA: Tintamarre, 2003. 208 pp.

("With few exceptions, the poets of "Les Cenelles" – the very first collection of poetry by Creoles of color – do not directly address their precarious situation in a South that was ever increasingly hostile to the racial caste to which they belonged. On the contrary, a naive reader might only discover the most pedestrian sorts of romantic subjects in these poems written by seventeen free men of color. However , why would Valcour B… refer to himself as an “unrecognized son of New Orleans?” What “cruel fate” might have forced P. Dalcour into exile? What is the source of the regret, the preoccupation with departure and the fear of betrayal that seeps from every line of these works?

"However gifted and diligent they might have been, free people of color were forced to live within the constraints of their fate as second class citizens. May the modern reader delve into these “modest Cenelles” conscience [sic, conscious] of the troubling context that underpins their creation. Without this awareness, the profound depths of their melancholy spirit will escape him completely" [publisher's description on website])

• Some content (?) (poems by Armand Lanusse, Joanni Questy, and Victor Séjour) repr. in "Paroles d'honneur: Écrits de Créoles de Couleur de la Nouvelle-Orléans. Critical Edition." Ed. Chris Michaelides. Shreveport, LA: Éditions Tintamarre, 2004.

-

Translations:

• "Les Cenelles: A Collection of Poems by Creole Writers of the Early Nineteenth Century". Trans. and ed. Régine Latortue and Gleason R. W. Adams. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1979. xli+165 pp. (Bilingual edition: French and English on facing pages. Includes annotations and biographical notes on the authors.)

• [Translation of selections from "Les Cenelles"]. "Creole Echoes: The Francophone Poetry of Nineteenth-Century Louisiana". Trans. Norman R. Shapiro. Intro. M. Lynn Weiss. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 2004.

-

Table of contents

-

(In the order in which items appear in 1845 edition)

Armand Lanusse / Introduction (9)

• Pierre Dalcour / Chant d'Amour [Pour chanter la beauté que j'adore, ô ma lyre] (17)

• B. Valcour / L'Heureux Pélerin [Ami tout sourit à mes voeux] (23)

• Camille Thierry / L'Amante du Corsaire [Petit oiseau de mer, toi qui reviens sans doute] (25)

• Michel St. Pierre / Le Changement [Dans une douce indifférence] (28)

• M. F. Liotau / Un An Après [Il est parfois, hélas! de ces choses passées] (30)

• Joanni Questy / Vision [Viens à moi, jeune fille] (32)

• Armand Lanusse / Le Dépit [Non, cela n'est pas bien, souffrez que je le dise] (36)

• B. Valcour / Épître à Constant Lépouzé [Je n'ai point oublié malgré mon long silence] (39)

• Pierre Dalcour / Un An d'Absence [Salut vertes savanes!] (42)

• Camille Thierry / Le Damné [Pour aplanir le chemin de la vie] (44)

• Michel St. Pierre / La Jeune Fille Mourante [Que ton sort est heureux, qu'il est digne d'envie!] (46)

• Armand Lanusse / Épigramme [Vous ne voulez donc pas renoncer à Satan] (48)

• M. F. Liotau / Eline [Rien n'est plus doux dans cette vie] (49)

• Pierre Dalcour / À une Inconstante [Toi dont l'onde est toujours limpide] (51)

• Auguste Populus / À Mon Ami P. [Dans les yeux d'une belle on peut lire aisément] (53)

• Victor Séjour / Le Retour de Napoléon [Comme la vaste mer grondat sous le tropique] (55)

• B. Valcour / À Malvina [Belle de grâce et belle de jeunesse] (60)

• Armand Lanusse / Un Frère au Tombeau de son Frère [Bien loin de tes parens, sur la rive étrangère] (62)

• Pierre Dalcour / Le Songe [traduit de l'espagnol de Fileno] [Je rêvais que, l'âme chagrine,] (64)

• Camille Thierry / Le Passé [Vous qui m'interrogez lorsqu'au sein d'une fête] (66)

• Numa Lanusse / Couplets Chantés à la Noce d'un Ami [Heureux amans, ô vous qui de Cythère] (68)

• Bo--rs / L'Orphelin des Tombeaux [Naguère un orphelin à la plaintive voix] (70)

• Nicol Riquet / Rondeau Redoublé [De francs amis demandent un rondeau] (75)

• Pierre Dalcour / Le Maudit [Pourquoi, pourquoi m'aimer, ô vierge enchanteresse] (79)

• Armand Lanusse / La Jeune Agonisante [Vous qui veillez près de mon lit, ma mère] (83)

• Camille Thierry / Le Nautonier [Confondons nos soupirs, confondons nos doux mots . . . ] (85)

• Desormes Dauphin / Adieux [Objet chéri, pourquo de ma tendresse] (87)

• B. Valcour / À Hermina [Amour, écoute un amant qui t'implore] (89)

• Joanni Questy / Une Larme sur William Stephen [Muse, un béant sépulcre engloutit un poète] (91)

• Pierre Dalcour / Au Bord du Lac [Viens ô ma bien-aimée] (95)

• Camille Thierry / Toi [Tout parle à ma douleur de cette jeune fille] (98)

• Armand Lanusse / À Elora [Éclairez, Elora, mon esprit incrédule] (101)

• Pierre Dalcour / La Foi, l'Espérance et la Charité [Mademoiselle, / Du bonheur, loin de vous, je niais l'existence] (103)

• Manuel Sylva / Soudain [Je renonce à toi, sombre Lyre] (104)

• Michel St. Pierre / À Une Demoiselle [Belle enfant que l'amour a pris soin de parer] (106)

• Armand Lanusse / Les Amans Consolés [O toi qui du jour fuis] (107)

• M. F. Liotau / Mon Vieux Chapeau [On dit que mon chapeau] (114)

• Camille Thierry / Adieu [Canal Carondelet, le vent du nord me chasse] (116)

• Nelson Desbrosses / Le Retour au Village aux Perles [Elle folâtre en ces lieux pleins de charmes] (118)

• Pierre Dalcour / Acrostiche [Reine de ma pensée, objet de mon ardeur] (120)

• Armand Lanusse / La Jeune Fille au Bal [Emma, vois-tu d'ici ce turbulent phalène] (121)

• Auguste Populus / Acrostiche [En voyant vos attraits, par leur charme séduit] (123)

• Camille Thierry / Le Réveil [A mes maux succédait un sommeil léthargique] (124)

• Numa Lanusse / Justification [On vous a dit, et vous l'avez pu croire] (126)

• B. Valcour / Le 11 Mars 1835 [Tu t'éloignais, je feignais de sourire] (128)

• Pierre Dalcour / Les Aveux [Je n'ai jamais dit: je t'aime] (130)

• Armand Lanusse / Mon Petit Lit Que J'Aime! [Mon petit lit que j'aime!] (132)

• M. F. Liotau / À Ida [Ce qui me plaît en toi, ce que j'admire et aime] (134)

• Jean Boise / L'Amant Dédaigné [Perfide amour, divinité rebelle] (136)

• Michel St. Pierre / Deux Ans Après [Ami, si l'espérance habite encor mon coeur] (138)

• Auguste Populus / Réponse à Mon Ami M. St. Pierre [Quand a cessé l'orage, et que le ciel plus beau] (140)

• Armand Lanusse / Jalousie [Allons jaloux, à vous tromper vous-même] (141)

• Camille Thierry / À Mademoiselle • • • [Vous qui demandez un soupir de mon âme] (143)

• B. Valcour / L'Ouvrier Louisianais [Ah! quoi, tu ris, tu ris jusques aux larmes] (145)

• Armand Lanusse / Le Songe [Poète à l'âme usée] (148)

• M. F. Liotau / Couplets chantés à une Noce [Combien du mariage] (150)

• B. Valcour / À Mon Amie [C'est toi qui m'inspiras mes désirs de poète] (152)

• Michel St. Pierre / Couplet [Avec plus de timidité] (154)

• Armand Lanusse / Le Prêtre et la Jeune Fille [L'ombre silencieuse envahit cette enceinte] (155)

• B. Valcour / Mon Rêve [Je sommeillais, trop aimable délire!] (158)

• Camille Thierry / À Celle Que J'Aime [Molles chansons, qui dorment dans mon âme] (160)

• M. F. Liotau / Une Impression [Église Saint-Louis, vieux temple reliquaire] (162)

• Louis Boise / Au Printemps [Tendre Printemps, viens rendre à la Nature] (164)

• Joanni Questy / Causerie [Mircé, si vous m'aimez, si vous êtes ma soeur] (165)

• Armand Lanusse / Le Carnaval [L'hiver, sémillante Palmyre] (167)

• Camille Thierry / Idées [Pauvre enfant! si j'eusse eu, pour me faire connaître,] (169)

• Pierre Dalcour / Caractère [Moi qui fais des vers par caprice] (171)

• Armand Lanusse / À Mademoiselle • • • [Jeune fille, dis moi, quand Dieu sur cette terre] (173)

• B. Valcour / Son Chapeau et Son Schall [Chapeau chéri] (175)

• M. F. Liotau / À un Ami Qui M'Accusait de Plagiat [Quoi, mon ami doute de toi, ma muse,] (177)

• Camille Thierry / L'Ombre d'Eugène B. [Je suis le malheureux, le suicide Eugène] (179)

• Michel St. Pierre / Tu M'As Dit Je T'Aime [O bonheur extrême!] (181)

• B. Valcour / À Mademoiselle Cœlina [Faible arbrisseau, battu par la tempête] (185)

• Manuel Sylva / Le Rêve [Un matin de beau temps, l'Aurore aux doigts de rose] (187)

• Camille Thierry / Parle Toujours [Parle toujours, vierge enfantine] (189)

• Armand Lanusse / Besoin d'Écrire [Je puis de tout plaisir braver la douce ivresse] (191)

• Pierre Dalcour / Vers Écrits sur l'Album de Mademoiselle *** [L'étoile qui scintille en la voûte des cieux] (193)

• M. F. Liotau / Un Condamné à Mort [Mon Dieu! qu'il est affreux le tourment que j'endure!] (194)

• B. Valcour / À Mademoiselle C. [Si je vous dis que je vous trouve belle] (195)

• Camille Thierry / Le Suicide [La vie est un affreux rivage] (197)

• Armand Lanusse / Le Portrait [Accours à ma voix] (199)

• Camille Thierry / Jalousie [De la jeune femme] (202)

• Armand Lanusse / Une Mère Mourante [Comme ton front est calme en ce moment, ma mère!] (205)

• Pierre Dalcour / Heure de Désenchantement [Je compte à peine un lustre après mes vingt années] (207)

(Alphabetized table of contents. The names of contributors are elaborated more fully here, on occasion, than in the 1845 edition.)

Dedication (by Armand Lanusse)

Introduction (by Armand Lanusse)

Boise, Jean [1 poem]

• "L'Amant Dédaigné" [Perfide amour, divinité rebelle]

Boise, Louis [1 poem]

• "Au Printemps" [Tendre Printemps, viens rendre à la Nature]

"Bo . . . ers" [= Bowers?] [1 poem]

• "L'Orphelin des Tombeaux" [Naguère un orphelin à la plaintive voix]

Dalcour, Pierre. [12 poems]

• "À une Inconstante" [Toi dont l'onde est toujours limpide]

• "Acrostiche" [Reine de ma pensée, objet de mon ardeur]

• "Un An d'Absence" [Salut vertes savanes!]

• "Au Bord du Lac" [Viens ô ma bien-aimée]

• "Les Aveux" [Je n'ai jamais dit: je t'aime]

• "Caractère" [Moi qui fais des vers par caprice]

• "Chant d'Amour" [Pour chanter la beauté que j'adore, ô ma lyre]

• "La Foi, l'Espérance et la Charité" [Mademoiselle, / Du bonheur, loin de vous, je niais l'existence]

• "Heure de Désenchantement" [Je compte à peine un lustre après mes vingt années]

• "Le Maudit" [Pourquoi, pourquoi m'aimer, ô vierge enchanteresse]

• "Le Songe" [traduit de l'espagnol de Fileno] [Je rêvais que, l'âme chagrine,]

• "Vers Écrits sur l'Album de Mademoiselle • • • " [L'étoile qui scintille en la voûte des cieux]

Dauphin, Desormes [1 poem]

• "Adieux" [Objet chéri, pourquo de ma tendresse]

Desbrosses, Nelson [1 poem]

• "Le Retour au Village aux Perles" [Elle folâtre en ces lieux pleins de charmes]

Lanusse, Armand [16 poems]

• "À Elora" [Éclairez, Elora, mon esprit incrédule]

• "À Mademoiselle • • • " [Jeune fille, dis moi, quand Dieu sur cette terre]

• "Les Amans Consolés" [O toi qui du jour fuis]

• "Besoin d'Écrire" [Je puis de tout plaisir braver la douce ivresse]

• "Le Carnaval" [L'hiver, sémillante Palmyre]

• "Le Dépit" [Non, cela n'est pas bien, souffrez que je le dise]

• "Épigramme" [Vous ne voulez donc pas renoncer à Satan]

• "Un Frère au Tombeau de son Frère" [Bien loin de tes parens, sur la rive étrangère]

• "Jalousie" [Allons jaloux, à vous tromper vous-même]

• "La Jeune Agonisante" [Vous qui veillez près de mon lit, ma mère]

• "La Jeune Fille au Bal" [Emma, vois-tu d'ici ce turbulent phalène]

• "Une Mère Mourante" [Comme ton front est calme en ce moment, ma mère!]

• "Mon Petit Lit Que J'Aime!" [Mon petit lit que j'aime!]

• "Le Portrait" [Accours à ma voix]

• "Le Prêtre et la Jeune Fille" [L'ombre silencieuse envahit cette enceinte]

• "Le Songe" [Poète à l'âme usée]

Lanusse, Numa [2 poems]

• "Couplets Chantés à la Noce d'un Ami" [Heureux amans, ô vous qui de Cythère]

• "Justification" [On vous a dit, et vous l'avez pu croire]

Liotau, M. F. [8 poems]

• "À Ida" [Ce qui me plaît en toi, ce que j'admire et aime]

• "À un Ami Qui M'Accusait de Plagiat" [Quoi, mon ami doute de toi, ma muse,]

• "Un An Après" [Il est parfois, hélas! de ces choses passées]

• "Un Condamné à Mort" [Mon Dieu! qu'il est affreux le tourment que j'endure!]

• "Couplets chantés à une Noce" [Combien du mariage]

• "Eline" [Rien n'est plus doux dans cette vie]

• "Une Impression" [Église Saint-Louis, vieux temple reliquaire]

• "Mon Vieux Chapeau" [On dit que mon chapeau]

Populus, Auguste [3 poems]

• "À Mon Ami P." [Dans les yeux d'une belle on peut lire aisément]

• "Acrostiche" [En voyant vos attraits, par leur charme séduit]

• "Réponse à Mon Ami M. St. Pierre" [Quand a cessé l'orage, et que le ciel plus beau]

Questy, Joanni [3 poems]

• "Causerie" [Mircé, si vous m'aimez, si vous êtes ma soeur]

• "Une Larme sur William Stephen" [Muse, un béant sépulcre engloutit un poète]

• "Vision" [Viens à moi, jeune fille]

Riquet, Nicol [1 poem]

• "Rondeau Redoublé" [De francs amis demandent un rondeau]

Séjour, Victor [1 poem]

• "Le Retour de Napoléon" [Comme la vaste mer grondat sous le tropique] [the poem was written in 1841 (Daley 1943: 9)]

St. Pierre, Michel [6 poems]

• "À Une Demoiselle" [Belle enfant que l'amour a pris soin de parer]

• "Le Changement" [Dans une douce indifférence]

• "Couplet" [Avec plus de timidité]

• "Deux Ans Après" [Ami, si l'espérance habite encor mon coeur]

• "La Jeune Fille Mourante" [Que ton sort est heureux, qu'il est digne d'envie!]

• "Tu M'As Dit Je T'Aime" [O bonheur extrême!]

Sylva, Manuel [2 poems]

• "Le Rêve" [Un matin de beau temps, l'Aurore aux doigts de rose]

• "Soudain" [Je renonce à toi, sombre Lyre]

Thierry, Camille [14 poems]

• "À Celle Que J'Aime" [Molles chansons, qui dorment dans mon âme]

• "À Mademoiselle • • • " [Vous qui demandez un soupir de mon âme]

• "Adieu" [Canal Carondelet, le vent du nord me chasse]

• "L'Amante du Corsaire" [Petit oiseau de mer, toi qui reviens sans doute]

• "Le Damné" [Pour aplanir le chemin de la vie]

• "Idées" [Pauvre enfant! si j'eusse eu, pour me faire connaître,]

• "Jalousie" [De la jeune femme]

• "Le Nautonier" [Confondons nos soupirs, confondons nos doux mots . . . ]

• "L'Ombre d'Eugène B." [Je suis le malheureux, le suicide Eugène]

• "Parle Toujours" [Parle toujours, vierge enfantine]

• "Le Passé" [Vous qui m'interrogez lorsqu'au sein d'une fête]

• "Le Réveil" [A mes maux succédait un sommeil léthargique]

• "Le Suicide" [La vie est un affreux rivage]

• "Toi" [Tout parle à ma douleur de cette jeune fille]

Valcour, B. [11 poems]

• "À Hermina" [Amour, écoute un amant qui t'implore]

• "À Mademoiselle C• • • " [Si je vous dis que je vous trouve belle]

• "À Mademoiselle Cœlina" [Faible arbrisseau, battu par la tempête]

• "À Malvina" [Belle de grâce et belle de jeunesse]

• "À Mon Amie" [C'est toi qui m'inspiras mes désirs de poète]

• "Épître à Constant Lépouzé" [Je n'ai point oublié malgré mon long silence]

• "L'Heureux Pélerin" [Ami tout sourit à mes voeux]

• "Mon Rêve" [Je sommeillais, trop aimable délire!]

• "Le 11 Mars 1835" [Tu t'éloignais, je feignais de sourire]

• "L'Ouvrier Louisianais" [Ah! quoi, tu ris, tu ris jusques aux larmes]

• "Son Chapeau et Son Schall" [Chapeau chéri]

-

About the anthology

-

• Includes 84 poems by 17 authors, all of them free men of color ("gens de couleur libres" of New Orleans).

• "The dedicatory verse of "Les Cenelles" prayed 'the Fair Sex of Louisiana' to accept the modest "cenelles" offered" (Johnson 1990: 409n.6).

• "The anthology bears an epigraph from A[lfred] Mercier: 'Et de ces fruits qu'un Dieu prodigue dans nos bois / Heureux si j'en ai su faire un aimable choix!' [And of these fruits that a god scatters abundantly in our woods / Fortunate am I, if I have been able to make a pleasing choice]" (Brosman 2013: 81).

• Armand Lanusse (1812-1867), the editor of the volume, was a poet and educator (Barnard 2001): "Contributors range from prosperous merchants such as cigar maker Nicol Riquet and mason Auguste Populus to such locally well-known figures as Lanusse, who worked to found black educational institutions; Joanni Questy, a widely read journalist for the militant newspaper La tribune de la Nouvelle Orléans; and Victor Séjour, whose highly successful playwriting career in Paris made him antebellum Louisiana's most distinguished writer" (Barnard 2001).

-

Anthology editor(s)' discourse

-

• "In the introduction to 'Les Cenelles,' Lanusse stressed the importance of education and urged young Louisianians to seek inspiration in the celebrated careers of Hugo and the larger-than-life Dumas, who was himself the grandson of an enslaved woman, Marie-Cessette Dumas, in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti)" (Bell 2014: 293):

Lanusse writes in the introduction: "De toutes parts un grand besoin d’instruction se fait sentir. On commence à comprendre que, dans quelque position que le sort nous a placés, une bonne éducation est une égide contre laquelle viennent s’émousser les traits lancés contre nous par le dédain ou par la calomnie. C’est donc avec un sentiment plein d’orgueil que nous voyons s’accroître chaque jour le nombre de ceux qui parmi nous parcourent maintenant de pied ferme la route si difficile des sciences et des arts, chacun dans la direction où il se sent attiré."

Among those pursuing the paths of education or enlightenment ("le progrès des lumières chez nous"), Lanusse seeks specially to highlight those engaged in literary endeavors , "la carrière que suivent avec tant de gloire les Hugo et les Dumas"; he emphasizes, as well, the obstacles, annoyances, and antipathies these literary aspirants encounter from those who have no taste for such pursuits. Lanusse acknowledges that "la profession d’homme de lettres n’est pas souvent à désirer"--it is hardly ever remunerative, to begin with, and Lanusse notes the sad, neglected end of various writerly figures, including the author of "Les Martyres de la Louisiane" [i.e., Auguste Lussan (d. 1842)]--but the born poet, he avers, will never abandon his calling.

• "Lanusse explains in the introduction that the collection is intended to defend his community and race, preserving for future readers its high level of cultural-educational achievement" (Barnard 2001). [Note: If so, this would refute the suggestion that the volume is virtually silent on racial issues. But the introduction is not, to my ears, so explicit a defense of "community and race" as Barnard's comment makes out. What we are meant to understand is, however, a different matter.]

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

Reviews and notices of original volume: "Les Cenelles: Choix de poésies indigènes". Ed. Armand Lanusse. La Nouvelle-Orléans: H. Lauve, 1845. 215 pp.

• "La Chronique, Journal politique et litteraire" 1 (1848): 34-35. (An anonymous review.)

"This important find was made, about the same time, by [Guillaume 1982 and Harris 1982]. Both quote at length from the review" (Johnson 1990: 409n.5).

-

Reviews and notices of 1945 revised edition published as "Creole Voices: Poems in French by Free Men of Color, First Published in 1845". Ed. Edward Maceo Coleman. Foreword H. Carrington Lancaster. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1945.

• In the author note to Edward M. Coleman. "William Wells Brown as an Historian." "Journal of Negro History" 31.1 [1946]: 47-59, we read: "Dr. Coleman, a product of the University of Southern California, is the head of the Department of History at Morgan State College in Baltimore. When a member of the Department of History at Dillard University in New Orleans some years ago he acquired through Attorney A. P. Tureaud of that city a copy of 'Les Cenelles,' an anthology of the verse in French of seventeen free men of color who in their native tongue gave the world in 1845 this expression of their thought. Dr. Coleman, through the Associated Publishers, has recently reprinted this work with a few other poems and the necessary documentation and annotation to justify its appearance under the title of 'Creole Voices'" (47n.).

-

Reviews and notices of 1979 reprint and English translation: "Les Cenelles: A Collection of Poems by Creole Writers of the Early Nineteenth Century". Trans. and ed. Régine Latortue and Gleason R. W. Adams. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1979. xli+165 pp. (bilingual edition: French and English on facing pages)

• Hoffmann, Léon-François. "Revue d'Histoire littéraire de la France" 81.3 (1981): 495-96. "JSTOR".

Hoffmann says the anthology includes 81 poems by 16 poets (495). The introduction by Latortue and Adams "nous apprend que les poètes des "Cenelles" étaient tous des mulâtres, bien qu'aucun des poèmes ne l'indique clairement" (495). The poems here take their inspiration from the escapist romanticism associated with Lamartine, and one is forced to admit that "la lecture des "Cenelles" ne révèle aucun talent oublié" (495).

In contrast to Haitian and African American poetry of the same era, this creole Louisiana poetry "n'avait, elle, rien d'engagé et s'interdissait même toute allusion à la réalité ambiante" (495). "Lorsqu'on sait dans quelle conditions ils furent composés, ces poèmes prennent une dimension pathétique pour le lecteur désormais conscient que leurs accents mélancoliques et leur grâce désuète sont le glas d'une classe condamnée" (495).

• Kein, Sybil. "Black American Literature Forum" 14.4 (1980): 166-67. "JSTOR".

"The allegiance these authors carried for France, not Africa, was a natural one, since the majority of their ancestors were from France. Some of these writers were educated in France; some lived there and produced their art there; some died there" (166).

"These writers who presumably "spoke" the Creole language, took pains to stick as closely as possible to the French language both in structure and style—again the idea of France as the 'mother' country" (166).

"[By the 1840s,] Americans were firmly settled in Louisiana, and their legal attitude toward black people, slave and free, was much more harsh than that of the French or the Spanish. Many creoles could not continue to live under a government that did not consider them any different from other colored people. It was easier to leave, and many did so. Among those creoles who stayed, the determination not to blend in with the rest of the colored freemen grew. In fact, this threat to their identity seemed to spark a new creativity, a new awareness of their unique status. In 1843, the first magazine to contain writings by creoles, "L'Album Litteraire" was issued. . . . two years later Lanusse published "Les Cenelles"" (166-67; quoting James Haskins)

"The Latourtue-Adams translation of "Les Cenelles" is appropriately placed in the (Yale University) Reference Publications in Afro-American Studies. . . . This volume certainly calls attention to the scope and variety of Black literature. Despite the 'labels,' Lanusse and the other writers of "Les Cenelles" were, above all, "Creole"" (167).

• Broussard, Mercedes. "Black Men Cried Softly." [Review of "Les Cenelles: A Collection of Poems by Creole Writers of the Early Nineteenth Century"] "Callaloo" 11/13 (Feb.-Oct. 1981): 211-14. JSTOR.

"Translation is never an easy art; translation of poetry is especially difficult. The translations by Latortue leave much to be desired. In some instances meaning is distorted to the point of conveying the opposite to the original" (211): Broussard gives several examples of mistranslation and asks, "In face of such inaccuracies in translation, of what value is the book?" (212).

Such value as it has rests with the original publication in French: "The volume proves there existed in New Orleans, twenty years before the Civil War ended slavery, a highly talented, extremely well educated class of black Creoles. It is not just that these men wrote poems: it is rather that they wrote poems which showed familiarity with European models, which made frequent use of classical imagery . . . These are not the signs of the 'natural' poet like Robert Burns; they are the signs of wide reading and cultivated intellect--characteristics not often associated with the pre-Civil War black man either in literature or in history books. The poems are of value because they help readers to ta fuller understanding of the black experience in America" (212).

"They do more. While not works of genius, the poems of 'Les Cenelles' reflect technical competence and artistic grace that makes them worth reading for themselves" (212). "The themes are the traditional Romantic ones. Love, often unrequited or hopeless, serves as a source of poetic inspiration . . . Patriotism, understandably more muted here than in English Romantic poetry, is evidenced in the sense of exile that accompanies the trip abroad to acquire an education. Death and the cruelty of fate also contribute to ta melancholia typical of the period. . . . Another recurring theme is that of the nature of poetry. The poet, with beauty as inspiration, is under compulsion to write. Invocations to a 'Muse' abound. Equally numerous are acknowledgements of debt to a mentor poet. . . . A major fault in some of the poems is an overemotionalism, a sentimentality too widely dispersed for proper intensity or genuine feeling" (213).

"Some readers will protest the classification of 'Les Cenelles' as black poetry. The themes and social problems treated are not specifically tied to the black experience, and except for one or two ironical references to 'plaçage'--the custom of having white males serve as 'protectors' for the comeliest mulatresses--the issue of race is not even mentioned. The lack of open protest does not indicate that the poets felt no discrimination, however. Reflections of stress may be found on any page in 'Les Cenelles.' But in 1845 Nat Turner had not long stopped swinging in the breeze; dirt had hardly settled over Gabriel Prosser and Denmark Vessey. Black men cried softly then, feeling that in realistic terms open revolt would accomplish nothing. The poets viewed education, on the other hand, as a means through which social change could be effected, and they made themselves examples of what they advocated. To borrow a phrase from Gordon Parks, it was a matter of a choice of weapons, not desertion of the field. That the poems were written gave the lie to the belief that blacks were incapable of achievement in a field calling for exercise of the highest human faculties. That the book was published bears testimony to the determination and the spirit of endurance that has always been the mark of black poetry" (213-14).

• Hayes, Jarrod. Review of "Creole Echoes: The Francophone Poetry of Nineteenth-Century Louisiana," trans. Norman Shapiro. "Nineteenth-Century French Studies" 35.3-4 (2007): 672-73. JSTOR.

In this review of "Creole Echoes," Hayes notes that some of these poems had been translated earlier in Régine Latortue and Gleason R. W. Adams's 1979 translation of "Les Cenelles": "Even in comparison with the English translations of poems in 'Les Cenelles', Shapiro's translations in 'Creole Echoes' are more accurate and more poetic, and this, in spite of the constraints of rhyme and meter that he chose to impose on himself (unlike the translators of 'Les Cenelles'). Compare, for example, the translation of Armand Lanusse's poem entitled 'Epigramme' ['Epigram'] included in both 'Les Cenelles' and 'Creole Echoes'. This poem relates the annual confessions of a 'bigote' [translated as 'zealot' in 'Les Cenelles' and 'zealous pietist' in 'Creole Echoes'], whom the pastor exhorts to abandon her sinful ways. She has one final request before doing so: '[A]vant que la grâce en mon âme scintille, / Pour m'ôter tout motif de pécher désormais, / Que ne puis-je, pasteur--Quoi donc?--'placer' ma fille?' ('Creole Echoes' 94). 'Les Cenelles' translates these verses as follows: '[B]efore grace sparkles in my soul, / To remove henceforth all incentive to sin, / Why can't I, father--what?--'establish' my daughter!' (95). Shapiro, however, translates, '"Before grace sparks my soul, tell me I can . . . / To rid all need of further sinning . . ." "What? . . ." / "Set up my daughter with a rich white man!"' (95, his ellipses). Shapiro's translation, here, is not only more accurate, but it also renders the poem's Louisiana specificity by more carefully referring to the institution of 'plaçage', or contractual relationships between white men and Creole women of color" (673).

-

Commentary on anthology

-

In chronological order:

• Fortier, Alcée. "French Literature in Louisiana." "PMLA" 2 (1886): 31-60.

"'Les Cenelles,' a word which signifies a small berry, is a collection of poems which are of some merit. The authors are Valcour, Boise, Dalcour, Dauphin, Desbrosses, Lanusse, Liotau, Riquet, St. Pierre, Thierry, and Victor Séjour, whose work 'Le Retour de Napoléon' was favorably received in France" (Fortier 1886: 44).

• Harrison, James A. "Native French Literature in Louisiana." "The Critic" (New York) no. 186 (23 July 1887): 37-38 and no. 187 (30 July 1887): 49-50. [Google Books https://books.google.com/books?id=a8JZAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA2-PA49#v=onepage&q&f=false ]

"Camille Thierry ('Les Vagabondes') and the circle of writers who collaborated on 'Les Cenelles' have given us many charming lines, favorably received even in France" (49).

This is the only comment directly on "Les Cenelles" in this article (and it makes no mention that the authors are "gens de couleur"), but there are other relevant remarks: for example, Harrison notes that Dr. Alfred Mercier "is a well-known contributor on Negro folk-lore to 'Mélusine'" (49); similarly, "In proverbial philosophy Lafcadio Hearn has made a charming beginning, collecting under the peculiar New Orleans 'patois' title of 'Gombo Zhèbes' ('Gombo aux Herbes') [1885] about fifty Negro-French aphorisms which he compares suggestively with those of five other Creole dialects. The footnotes are garnished with piquant scraps of song and folk-lore, most appetizing to lovers of these things" (49-50). It is apparent from this that Harrison does not use "Creole" to refer to people of mixed-race background, but rather to people of "Latinate" (French-Spanish), rather than "Anglo-Saxon" culture. Indeed, although Harrison refers to "the much-maligned . . . Creole race"--"A glance over the 'table de matières' of the 'Athènée Louisianais' from 1876 to 1887 will show the literary activity of the much-maligned but most gifted and accomplished Creole race" (50)--he means by this something other than what some modern scholars mean, when they refer to the Creoles of Louisiana. Thus, Harrison brings his survey to a close by asserting that, "This summary 'aperçu'--which is deeply indebted to Alcée Fortier of the Tulane University of Louisiana for many of its facts and dates--is sufficient to repel the allegations of intellectual indolence constantly brought against an elegant and amiable race by people whose ignorance is only equalled by the glibness with which they write and talk of it. To confound such a race with the 'dagoes' and quadroons by whom they are surrounded--to introduce confusion between them and the degraded Ethiopia Minor about them in the minds of hunters for the picturesque--to avail oneself of the oblique suggestiveness of an abominable lingo in order to give people geographically remote an 'idea' or a 'notion' of beautiful and romantic Louisiana and its people,--this is not simply a literary crime: it is an injustice that cries to heaven. To be made 'picturesque' at the expense of every principle of truth and justice--to go down to posterity clad in gorgeously colored slanders, spotted as a leper--this is anything but an enviable fate, and it is no wonder that the Creoles of Louisiana have grown restive under the process. Probably Marsyas did when he was being flayed" (50). The distress of white, francophone Creoles at being confounded with, mixed in with, racial and ethnic others, could hardly be given more vivid expression!

In the first part of this article, Harrison makes clear his understanding of the ancestry of the Creoles: he writes that, in Old New Orleans, the botanical "rare exotic blooms" and the buildings with "a glint or a suggestion of Spanish-French architecture," make you think "you are no longer in America--you are in France or Spain, and the polygot jabber from the Marché Français near by confirms you in your illusion" (37). "Wherever the French or the Spanish go, they leave indelible traces of themselves--light as a snail's trace mayhap, but still indestructible. From the beginning they entangled themselves with the fates and fortunes of Louisiana . . . its plastic civilization has received an imprint which, in spite of the strong-flavored, domineering Anglo-Saxon population thickly settled along its 'bogues' and 'bayous', is as clear as the lines of a cameo, as poetic and full of grace as the original Bordeaux and Provence from which much of it came. This is perceptible not only in its own native [French] literature, but in the attitude of mind sustained by American writers of Louisiana birth when treating of Creole life from their own point of view. There is an infiltration of old Spanish-French life in the romances of Cable no less than in the histories of Martin and Gayarré. A stroll through the streets of New Orleans, abounding as New Orleans is in an exuberant and aggressive 'Anglo-Saxonism,' will show even a careless promenader how this delicate suave Latin spirit has moulded all it has touched, has refined and transfigured manners, has cast a veil of elegance over personal habits and intercourse, has permeated the shops as well as the 'salons,' and left in the air indefinable trails and associations at once light and tenacious, like the Madonna-veils of the poets. This is why in an intellectual direction New Orleans has never abandoned France and her darker cousins of Spain, why her mental ancestry and affiliations lead straight across the Atlantic . . . There is nothing so self-perpetuating as the Latin grace: the 'négrillons' of New Orleans possess it as fully as their former masters and mistresses; and along with it, among the cultivated Louisianais, goes a literary fealty which nothing can disunite from Old France" (37).

Harrison is at pains to argue both that the Creole culture is fundamentally linked to and imitative of that of France and that it has an originality and a specificity to Louisiana: "Naturally, from what has been said of the strength of their ancestral associations, the Louisianais have been more or less imitative in their literary productivity. . . . The scions of the old French families streamed and still stream to France, and return burdened with its pollen. The conventional life led by the girls is modelled after that of the old country, and the shadow of the confessional overarches the religious life of the State. . . . For all this, Louisiana is not wholly mimetic in its native French literature. The cultivated people speak beautiful French kept perennially pure by contact with the fatherland . . . The abundant folk-lore of the 'habitants', the naïve utterances of the proverb-loving 'gens de couleur' (as they like to call themselves), the traditions of the 'Cadjens, the fund of historic and picturesque adventure laid up in the rich honeycombs of family legend, the many-colored threads of French, Spanish, and Indian history through which the shuttle of the historian may fly and weave captivating patterns, are all material which lies partly virgin--are auriferous enough for future chroniclers and poets to hammer into delectable image-work" (37).

Harrison's discussion reminds us that up until the later 19th century, "créolité" was "not [primarily] a racial label" but either a term distinguishing those born in the New World from those born in the Old, or a cultural (or cultural-ethnic) label, distinguishing those of French and Catholic culture (and descent) (whether "creole" in the old sense or Haitian or Acadian/Cajun in background), from those of the anglophone (and Protestant) culture prevalent in much of the rest of the United States. "People of any race can and have identified as Creoles" (Wikipedia, sv "Louisiana creole people"). But the use of the term "creoles of color" to refer specifically to black and mixed-race creoles suggests that the default sense of "Creole" in this older usage was with reference to white Creoles (as is evident in Harrison's usage). But from the later 19th century the term "creole" came increasingly to be associated with the free people of color (gens de couleur libres) and, after World War I, the term was more particularly inflected as persons of mixed race (which most of the gens de couleur libres in the antebellum era were). Harrison in 1887, however, is fighting against this shift in usage and "defending" (as we have seen) the implied whiteness of the Creoles in Louisiana (except when this "generic" term is specified as referring to the 'gens de couleur libres' or the "Negro-French" or the "Négrillons" of Louisiana).

Shirley Thompson (2001) argues that the term "Creole" originally referred to the native-born community descended from Old World arrivants (of whatever race, European or African). But "[a]fter the Civil War and into the twentieth century, writers and historians of New Orleans"--people like Harrison in 1887--"racialized the term, claiming that only 'pure whites' could be called 'Creoles'" (Thompson 2001: 259n.2).

• Desdunes, Rodolphe Lucien. "Nos Hommes et Notre Histoire". Montreal: Arbour et Dupont, 1911. [Louisiana Anthology: https://www2.latech.edu/~bmagee/louisiana_anthology/texts/desdunes/desdunes--nos_hommes.html] [Atramenta: https://www.atramenta.net/lire/nos-hommes-et-notre-histoire/13695/11#oeuvre_page] English trans. as "Our People and Our History: Fifty Creole Portraits". Trans. and ed. Sister Dorothea Olga McCants. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1973. [Google Books preview https://books.google.com/books?id=xlTl1-SnsiIC&lpg=PA10&ots=erzQcRs127&dq=%22les%20cenelles%22&pg=PA10#v=onepage&q&f=false ] See esp. "Chapter II: "Les Cenelles": Mr. Armand Lanusse and His Times" "Chapter III: A Dedication: The Collaborators of "Les Cenelles": Some Biographical Sketches" and "Chapter IV: The Collaborators of "Les Cenelles" (Continuation): Some Biographical Sketches." (pp. 10-24, 25-47, and 48-60). (Desdunes was a descendant of one of the contributors to "Les Cenelles".)

Desdunes remarks of the title "Les Cenelles" only that ""cenelles" were 'the fruit of the hawthorn bush.' Beyond that, he could but speculate that the small size of the fruit symbolized the modesty of the poets who put together the collection, that the thorniness of the haw bush symbolized the 'difficulty of the undertaking' in 'surroundings so discouraging to their poetic inclinations,' and that the shrub's 'white and colored' flowers indicated the 'purity of their intentions' and their desire to 'give a bright color to the dark hue of their lot'" (Johnson 1990: 408; quoting from Desdunes 1911: 15).

Desdunes notes that the volume is "très rare aujourd'hui."

• Caulfeild, Ruby Van Allen. "The French Literature of Louisiana." New York: Institute of French Studies, Columbia University, 1929. [HathiTrust: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/4174484.html]

Caulfeild treats "Les Cenelles" as a collection of love poems: “'Les Cenelles, choix de poésies indigènes' is dedicated ‘Au beau sexe Louisianais’. The first poem is a ‘Chant d’Amour’ and most of the others are love poems also, for with very few exceptions, each one of the sixteen [sic, 17] authors who contributed to this collection sang praises of some lady-love. Some of the verses are mere exercises in rhyming and have no claim to be called poetry” (240).

• Tinker, Edward Larocque. ""Les Cenelles", Afro-French Poetry in Louisiana." "The Colophon" (New York) 11.14 [part 3] (July-Sept. 1930); also reprinted separately: New York: Spiral Press, 1930. 16 pp. (plus—or including?—8 pp. of facsimiles).

[See also Tinker 1932, below]

• "M. V." "Les Cenelles." "Journal de la Société des Américanistes" 23.1 (1931): 251. [Persée http://www.persee.fr/doc/jsa_0037-9174_1931_num_23_1_1100_t1_0251_0000_2 ]

"La publication de ce livre, le premier qu'osèrent faire imprimer aux États-Unis des "gens de couleur", avait presque l'allure d'un manifeste. Plusieurs des membres de cette sombre Pléïade avaient d'ailleurs fait d'excellentes études en France, dont les collèges se montraient fort bienveillants à leur égard: Armand Lannusse suivit les cours de l'École polytechnique et Camille Thierry publia plus tard un volume de poésies à Bordeaux. Victor Séjour, dont les pièces connurent de nombreux succès sur les scènes parisiennes, participa également aux "Cenelles", petit livre devenu depuis longtemps introuvable, et dont, d'après les reproductions, la très curieuse ornementation typographique ne semble pas un des moindres attraits. Nous devons savoir le pus grand gré à notre collègue de la Société des Américanistes M. E. L. Tinker de nous avoir fait connaître les auteurs de ces singulières poésies lousianaises. [See Tinker 1930, below]" (251).

• Tinker, Edward Laroque. "Les écrits de langue française en Louisiane au XIXe siècle." Paris, 1932. [See also Tinker 1930, above.]

Frans C. Amelinckx remarks that, "Although in many aspects [this work] is a source of information, Tinker has the habit of fantasizing the writers' biographies. In my own research on Michel Séligny and Camille Thierry, I have found some rather bizarre assertions [in Tinker] . . . Unfortunately, many scholars [including Lynn Weiss in the introduction to "Creole Echoes"] still accept at face value the fruit of Tinker's imagination" (Review of "Creole Echoes," trans. Norman Shapiro and intro. Lynn Weiss. "Louisiana History" 47.1 [2006]: 111-13, at 112).

• Tinker, Edward Laroque. Letter to W. E. B. Du Bois. 14 April 1934. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, U of Massachusetts, Amherst. [https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b072-i185]

Tinker encloses for Du Bois a copy of the article he had published in "The Colophon" in 1930 about "Les Cenelles" and adds: "Of the original publication I have only seen three copies--one at the Howard Library in New Orleans and the other two are i my collection of Franco-Americana. One of my copies is perfect and the other, which I got first, lacks one page of the index, which can be supplied with a photostat."

• Rousseve, Charles B. "The Negro in Louisiana: Aspects of His History and His Literature". New Orleans: Xavier UP, 1937

"Of paramount importance is the publication, in 1845, of "Les Cenelles", the first anthology of Negro verse in America. Its 215 pages resulted from the collaboration of seventeen New Orleans poets, several of whom were acclaimed in literary circles in France" (quoted in Kein 1980: 166). After quoting this passage, Sybil Kein remarks that the use of the term "Negro" here "points up the plight of the 'Creole' authors of "Les Cenelles", who in all probability would have hesitated to refer to themselves as 'Negro'" (Kein 1980: 166).

• Daley, T. A. "Victor Séjour." "Phylon" 4.1 (1943): 2, 5-16. "JSTOR".

• Bontemps, Arna. “Special Collections of Negroana.” "The Library Quarterly" 14.3 [July 1944]: 187-206:

In describing how Arthur B. Spingarn built his collection of writings by Negro authors, Bontemps notes that "Abbé Grégoire's book of Negroes of achievement (Paris, 1808) offered a good point of departure. The names included in this volume were followed through the catalogs of the great American libraries, the British Museum, and the Bibliothèque Nationale. An anthology called 'Les Cenelles', published in New Orleans in 1845, became even more useful. Written in French by free men of color, 'Les Cenelles' was the earliest collection of poetry by Negro poets in the United States. Its contributors, pursued singly, turned out to be surprisingly good material" (194).

• Editorial note in "Phylon" 4.1 (1943):

"The free Negroes of Louisiana in 1845 published "les Cenelles", an anthology of their own poetry and one of the first anthologies in America" (50n.1).

• Anderson, Willie Burke. "A Critical Study of "Les Cenelles"." MA Thesis. Atlanta U, 1947. [Now Clark Atlanta University] [Digital Commons http://digitalcommons.auctr.edu/dissertations/2460/ ]

• Baker, Houston A., Jr. "Balancing the Perspective: A Look at Early Black American Literary Artistry." "Negro American Literature Forum" 6.2 (1972): 65-71. JSTOR:

“The most interesting output [of the Romantic poets] is that of the Creole poets of early nineteenth century New Orleans; their volume, 'Les Cenelles,' is the first published anthology of black verse in America. The Creoles—or Les Gens du Coleur—constitute an interesting phenomenon in American history, and their sophisticated and delicate verse in French is worthy of more study than it has received” (516).

• Sherman, Joan R. "The Creole Poets of "Les Cenelles"." "Invisible Poets: Afro-Americans of the Nineteenth Century". Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1974.

• Latortue, Régine, and Gleason R. W. Adams. Introduction. "Les Cenelles: A Collection of Poems by Creole Writers of the Early Nineteenth Century". Trans. and ed. Régine Latortue and Gleason R. W. Adams. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1979.

Latortue and Adams, in their introduction to their 1979 translation of "Les Cenelles", remark on the near-complete silence of these poems on racial identity and its social implications in early 19th century Louisiana: this silence needs to be placed in relation to the laws suppressing open discourse about such issues: "by 1830 legislation had been passed which 'prohibited the writing or publishing of any matter tending to breed discontent among the free people of color or insubordination among the slaves, the penalty involved being life imprisonment at hard labor or death. . . . At the slightest whim of the most wretched citizen or some rascally officer, the most respectable among the gens de couleur were subjected to arrest, violence and imprisonment'" (quoted in Kein 1980: 166).

• Baudouin, Robert I. "Les Cenelles: A Collection of Romantic French Language Verse." BA Thesis. Tulane U, 1981. ii+50 pp.

• Guillaume, Alfred J., Jr. "Love, Death, and Faith in the New Orleans Poets of Color." "Southern Quarterly" 20.2 (1982): 126-44. (Repr. in "In Old New Orleans." Ed. W. Kenneth Holditch. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1983.)

• Harris, M. Roy. ""Les Cenelles": Meaning of a French Afro-American Title from New Orleans." "Revue de Louisiane/Louisiana Review" 11.2 (1982): 179-96.

Recounts the publication history of the volume (Johnson 1990: 407n.2) as well as misunderstandings of the volume's title by various 20th-century writers and commentators: "Some mistook the small size of the fruit for what they supposed to be the small size of the hawthorn bush; some focused on the bush's variegated flowers or on its thorns; some contented themselves with translating the term simply as 'haws;' and some arbitrarily assigned it the meaning 'holly berries'" (Johnson 1990: 408, summarizing discussion in Harris).

• Schmit, P. B. "Cultural Treasure Acquired." "Historic New Orleans Collection Newsletter" 5.4 (1987 Fall). [a discussion of "Les Cenelles" and of Free Blacks in New Orleans during the 1840s]

• "Dictionary of Louisiana Biography" (1988) and its ten-year supplement (1998): for biographical information on the contributors to "Les Cenelles."

• Johnson, Jerah. "Les Cenelles: What's in a Name?" "Louisiana History" 31.4 (1990): 407-10. "JSTOR".

"Les Cenelles" is "the single most important piece of antebellum black literature ever written" (407).

The title has not been fully understood: "Desdunes was on the right track when he correctly, if imprecisely, noted that "cenelles" were hawthorn fruit, "i.e.", haws. But not being a man of the kitchen, he did not realize that they were the fruit of a particular kind of hawthorn, and consequently got off the track by focusing on the thorns and blossoms of the shrub rather than on the special qualities of the fruit itself. In nineteenth-century New Orleans French, "cenelles" were not just any haws, of which there were several native varieties, but specifically May haws, sometimes also called apple haws. Alone among local varieties, the May haw was edible" (408).

"May haws, "Cratagus aestivalis" or "opaca", were, when mature, one-half to three-quarters of a [sic] inch in diameter, shiny bright red with juicy flesh, and crowned by a conspicuous, hard, brown calyx. Their thorny trees, small, twenty-to-thirty-feet high, with round, compact heads, had very special habitats. They grew only in isolated, open spots in swamps or shallow ponds, for their roots required a constant and plentiful supply of water and their foliage full sunlight. As they ripened in May, their fruit fell into the // surrounding water, whence they could be strained up by anyone willing to brave the resident infestation of alligators and water moccasins. But the prizes were worth the danger, and May haw gathering became a favorite spring adventure for local boys and young men" (408-09).

Once gathered, cleaned and stripped of their calyxes, the May haws were boiled, strained, sugared, in a repeated process to make May haw jelly, taking "its place on the creole table as the finest, rarest, and most highly prized confiture in the New Orleans culinary hierarchy" (409).

Harris 1982 considered the possibility that "cenelles" refers to May haws in particuar—rather than haws generally (the fruit of the hawthorn bush or tree)—but he concluded that the more specific reference was only speculative, lacking "any written source precisely defining "cenelles" as May haws" (410). Johnson comments: "But if one takes Harris's considerable assemblage of literary and linguistic evidence that favor a reading of "cenelles" as May haws, and adds to it what we know about the folk practice of gathering May haws for jelly making, all the pieces of the puzzle suddenly fall into place and make sense. The folkway evidence more than compensates for the lack of a precise written definition that bothered Harris, and the weight of the total body of evidence makes the conclusion obvious" (410).

"The authors and editor of "Les Cenelles", all free men of color in antebellum New Orleans, in calling their pieces "May haws", and presenting them to the 'Fair Sex of Louisiana,' subtly and poetically evoked the image of small, uniquely flavored, and rare local delicacies that struggled for life in surroundings so hostile as to make the very gathering of them a dangerous travail, but one worth the risk because of the richness of the reward" (410).

• Bell, Caryn Cossé. "Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana". Baton Rouge: Lousiana State UP, 1997. 114-23 (discussion of "Les Cenelles").

• Cheung, Floyd. ""Les Cenelles" and Quadroon Balls: 'Hidden Transcripts' of Resistance and Domination in New Orleans, 1803-1845." "Southern Literary Journal" 29.2 (1997): 5-16.

• Kinnamon, Keneth. "Anthologies of African-American Literature." "Callaloo" 20.2 (1997): 461-81.

"Les Cenelles" is "a collection of eighty-five [sic, 84] poems by seventeen free New Orleans Creoles writing in their native French. Eighteen [sic, actually 16] of these are by the editor Armand Lanusse, who also provides an introduction. . . . Totally disengaged from issues of slavery and emancipation, these poets, writing of love, friendship, and hedonistic pleasure, are squarely in the French Romantic tradition, prosodically as well as thematically" (461).

• Fabre, Michel. "The New Orleans Press and French-Language Literature by Creoles of Color." "Multilingual America: Transnationalism, Ethnicity, and the Languages of American Literature". Ed. Werner Sollers. New York: New York UP, 1998. 29-49.

• Fabre, Michel. "'In Emulation, but without Jealousy': On the Literature of the New Orleans Gens Libre de Couleur." "Holding Their Own: Perspectives on the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the United States". Ed. Dorothea Fischer-Hornung and Heike Raphael-Hernandez. Tübingen: Stauffenburg, 2000. 17-31.

• Barnard, Philip. "Les Cenelles." "The Concise Oxford Companion to African American Literature". Ed. William L. Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris. New York: Oxford UP, 2001. [Online edition selectively updated in 2011.]

Barnard repeats the imprecise claim that "cenelles" means holly or hawthorne berries, but a more specific elucidation of the term is available in Johnson 1990 (see above).

"In content and form, the eighty-four poems in Les Cenelles are modeled on French romanticism. They are self-consciously elegant, conventional poetic statements (conventionality here is an index of sophistication) ranging from the facetious to the elegiac and tragic. Principle themes are love, both disappointed and fulfilled; disillusionment and the contemplation of death (five poems concern suicide); and the vicissitudes and dignity of the poetic vocation. Considering its general emphasis on disappointment and disillusionment, the collection is not, as some commentators suggest, primarily a group of light, sentimental love poems. Love in romantic poetry is a surrogate for higher aspirations that for this racially defined community remain frustrated and unfulfilled. When love appears in positive terms, it is cultural refinement and elevation rather than simple passion that is being affirmed."

• Haddox, Thomas F. "The 'Nous' of Southern Catholic Quadroons: Racial, Ethnic, and Religious Identity in "Les Cenelles"." "American Literature" 73.4 (2001): 757-78.

-

• "Creole Echoes." Online exhibition. 2001 (Louisiana State U):

The exhibit includes a useful discussion of "The Free People of Color" (esp. in antebellum New Orleans) and of the white Creole support of the Confederacy during the Civil War (and their efforts to engage France in support of the Confederacy) ("The Latin Race in Louisiana"). More directly relevant to "Les Cenelles," it also includes a discussion of "Armand Lanusse and 'Les Cenelles.'"

The very act of publishing "Les Cenelles" involved an act of racial defiance: "The 'Gens de Couleur Libres' of New Orleans were free, but they faced many restrictions in a city where they aroused both jealousy and suspicion. In 1845, defying the ban put on the publication of works by people of color, New Orleans educator and poet Armand Lanusse gathered eighty-five [sic] poems written by seventeen free black Louisiana poets and published them under the title 'Les Cenelles.' While Lanusse remained in the increasingly hostile New Orleans to continue his activism in the defense of people of color, several of the other contributors to 'Les Cenelles' left Louisiana. Pierre Delcour, Camille Thierry and Victor Séjour preferred life in France, where they might encounter the luminaries of the French literary world, to the increasingly restrictive atmosphere of their Louisiana home."

The exhibition also comments on the poems collected in "Les Cenelles": "The poets who wrote for Les Cenelles tended to draw exclusively on commonplace romantic themes of melancholy and fantasy, individualism and the mal du siècle, while remaining silent about the political implications of their racial status. But in his poetry Lanusse alludes to highly charged issues like the institution of plaçage (see “Épigramme” )—the arranged extra-marital unions between young free women of color and wealthy white men."

The complexity of the situation these free blacks found themselves in is made evident in Lanusse's actions after "Les Cenelles" was published: "Lanusse took part in the building of a catholic school for poor orphans of color, l’Institution Bernard Couvent. The school was completed in 1848 and Lanusse became its director in 1852, a position he was to occupy until his death [in 1867]. While Lanusse fought with the Confederate Army during the Civil War, his disgust at the treatment that black people received drove him to actively encourage many of them to leave the oppression in Louisiana for more hospitable racial climates."

-

Creole Echoes (LSU online exhibition)

-

• ""Les Cenelles"." "Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience". Ed. Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. 2nd ed. 5 vols. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. 3:554. [Google Books preview https://books.google.com/books?id=TMZMAgAAQBAJ&lpg=RA2-PA554&dq=les%20cenelles&pg=RA2-PA554#v=onepage&q&f=false ]

This unsigned entry includes one howler—"Napoleon, French emperor in the early eighteenth century"—and quotes commentary on "Les Cenelles" but does not identify the sources of the comments.

• Haddox, Thomas F. "Catholic Miscegenations: The Cultural Legacy of "Les Cenelles"." "Fears and Fascinations: Representing Catholicism in the American South". New York: Fordham UP, 2005. 14-46.

• Hobratsch, Ben Melvin. "Creole Angel: The Self-Identity of the Free People of Color of Antebellum New Orleans." MA thesis, U of North Texas, 2006.

• Kress, Dana. "Pierre-Aristide Desdunes, "Les Cenelles", and the Challenge of Nineteenth Century Creole Literature." "Southern Quarterly" 44.3 (2007): 42-67.

• Thompson, Shirley Elizabeth. "Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans". Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2009. Esp. 110-30.

• Bonner, Thomas, Jr. "New Orleans and Its Writers: Burdens of Place." "Mississippi Quarterly" 63.2 (2010): 195-209.

"When one reads 'Les Cenelles', the 1845 collection of poems by free 'men' of color in New Orleans, there is only the most indirect and occasional consideration of race and local issues. Alfred J. Guillaume [1982/1983] raises the question: 'How can one explain this absence of psychological and public reality?' He responds himself: 'At the time . . . literature that might incite discontent among the colored populace was prohibited, and so the poets, whatever their true feelings about the city and their place in it, could write nothing of daily experience.' Rather they sought relief in exploring 'themes of love, women, nature and personal sadness.' Guillaume further observes that 'the New Orleans poets of color differed from the French Romantics [whom they considered as their models] whose melancholy dirges abound in local color' (138). In their very denial of the obvious, they affirmed the presence of race as a local issue" (198).

• Davis, Thadious M. "Politics & Paysans: Multicultural Louisiana & the Space of the Créolité." "Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, and Literature". Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2011. 185-256. JSTOR.

"Because it was written in French, 'Les Cenelles' was . . . often overlooked in literary histories of the United States and in accounts of African American literature, despite the fact that Edward Maceo Coleman, a professor of history at Morgan State in Baltimore, published 'Creole Voices: Poems in French by Free Men of Color' in 1945, on the 100th anniversary of the appearance of 'Les Cenelles.' However, only Coleman's preface and the foreword by H. Carrington Lancaster, a Romance languages professor at Johns Hopkins, were in English. Werner Sollers suggests that the neglect of writing such as 'Les Cenelles' is a direct consequence of the 'Creole' position of the writers both because it 'defied an easy "national" location in an age in which literary history was imagined foremost to be the history of national literatures,' and because it was 'a "racially ambiguous" term in an era in which the color line was drawn more and more sharply.' Perhaps Sollers is correct in his speculations" (217).

"Recent critiques point to the lack of protest in the poetry published in 'Les Cenelles' and the affect of French romanticism without the political content, but Caryn Cossé Bell, in 'Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition,' has rightly read the layered social criticism in the collection. I want to suggest that following Bell, closer attention to the poems and poets in context and in relation to their referents may yield more ways to reconstruct the political content of 'Les Cenelles'" (220).

Davis herself suggests that the poet identified in "Les Cenelles" as "B. (Valcour)" (in the table of contents) and as "Valcour B+++" (at the end of one of his poems) and as "Valcour" (at the end of the other poems) and who is treated by modern scholars as an unidentified individual named "B. Valcour" should actually be seen as someone using "Valcour" as a pseudonym, with "Valcour" being an allusion to the Marquis de Sade's "Aline and Valcour or, The Philosophical Novel" (published in 1795 and banned in 1815 in France "for its sexually graphic content") (221). "Whether or not a strong argument can be made for Valcour choosing a space within 'Les Cenelles' to sign himself cryptically and symbolically as one resisting oppression and envisioning an alternative new world signified by the French Revolution and its connection to the American Revolution, his naming does appear unequivocally as a space of difference and his poem as a site of political consciousness" (223).

• Dixon, Nancy. "Armand Lanusse's 'A Marriage of Conscience,' "Les Cenelles", "Plaçage", and the Censorship Law of 1830." "Turning Points and Transformations: Essays on Language, Literature and Culture". Ed. Christine DeVine and Marie Hendry. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2011. 111-23.

• Pratt, Lloyd. "The Lyric Public of "Les Cenelles"." "Early African American Print Culture". Ed. Lara Langer Cohen and Jordan Alexander Stein. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2012. 253-73.

• Brosman, Catharine Savage. "Poetry by Mid-Nineteenth-Century Free People of Color." "Louisiana Creole Literature: A Historical Study". Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2013. 80-92.

"The most important collective work of the literary community formed by the 'gens de couleur libres' was an anthology called 'Les Cenelles: choix de poésies indigènes' (1845), prepared by Armand Lanusse. . . . The term 'indigenous' indicates simply that the contributors were of native[-born] stock. The volume consists of eighty-five [sic] poems. . . . The anthology was an admirable expression of consciousness by a group representing the larger caste and should not be dismissed as an elitist publication by privileged authors. Whether it was an antagonistic gesture to the white literary community is doubtful; but it expressed pride" (80).

"'Les Cenelles' shows the influence of the French Romantics, especially Lamartine, from whom lines are frequently quoted as epigraphs. . . . One reviewer called the poems 'aimables' but derivative, and also repetitious, 'monotonous'--features, he acknowledged, of Victor Hugo's and Lamartine's work also, but offset there by poetic virtues and frequent flashes of genius. . . . Calvin Claudel, a folklorist, spoke of the 'artificiality of this literary coterie in their imitation of the Classical French literary style.' He is mistaken to call it 'classical.' The alexandrine, though a classical marker, endured long into the nineteenth century and was the form of choice for most nineteenth-century poets; in other respects the poems are in the established Romantic mode. Claudel found their writing too derivative: 'They lack the creative originality of the uneducated singers mentioned by [George Washington] Cable'" (81). (Brosman expresses scepticism about this romantic elevation of "folk" authors above "learned or intellectual" authors who work in relation to established conventions: "Authors' background, audience, and taste should be taken into account in such an assessment" [81].)

"Some poems in 'Les Cenelles' are in the heroic vein of French Romanticism, well illustrated by Victor Hugo. Many are love poems. While it may be assumed that the beloved is generally a Creole of Color (even those who are blonde with blue eyes), this is by no means certain. Still others concern nature or death, often with Christian overtones. Régine Latortue and Gleason R. W. Adams [1979] assert that the poetry is 'superficial and imitative since it lacks the subtext of revolution and liberty which existed in the works of the best French Romantics' (xiii). This statement is oversimplified; countless well-known poems by Lamartine and Hugo have no connection to politics. Furthermore, Alfred de Vigny was a conservative, and Alfred de Musset was apolitical" (82).

• Clark, Emily. "The Strange History of the American Quadroon: Free Women of Color in the Revolutionary Atlantic World." Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2013.

Re "Les Cenelles": "The collection's most prominent contributors were all of Haitian descent, including [Armand] Lanusse and his brother, Numa Lanusse, Camille Thierry, and Victor Séjour. The group's identification with Haiti and its struggles was strong. Numa Lanusse organized a collection in 1832 from nearly 200 free black Orleanians to relieve the suffering of hurricane victims in Les Cayes and Jérémie in southern Haiti" (157).

• Bell, Caryn Cossé. "Pierre-Aristide Desdunes (1844-1918), Creole Poet, Civil War Soldier, and Civil Rights Activist: The Common Wind's Legacy." "Louisiana History" 55.3 (2014): 282-312. JSTOR.

• Giacoppe, Monika. "More Than Music and Food: Teaching about Cajun and Creole Cultures and Peoples." "Multiethnic American Literatures: Essays for Teaching Context and Culture." Ed. Helane Adams Androne. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015. 29-54, esp. 41-48.

• Guenin-Lelle, Dianne. "Nineteenth-Century French Creole Literature: The Final Chapter of French Colonialism." "The Story of French New Orleans: History of a Creole City." Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2016. 139-66.

"Like [Victor Séjour's] 'Le Mulâtre' this work should be understood as socially engaged literature protesting the limits on civil rights that were becoming more and more dangerous for free people of color" (149).

• Pratt, Lloyd. "Les Apôtres de la Littérature and "Les Cenelles"." "The Strangers Book: The Human of African American Literature". Philadelphia: U of Pennsylavania P, 2016. 63-91.

• Wegmann, Andrew N. "To Fashion Ourselves Citizens: Colonization, Belonging, and the Problem of Nationhood in the Atlantic South, 1829-1859." "Race and Nation in the Age of Emancipations." Ed. Whitney Nell Stewart and John Garrison Marks. Athens: U of Georgia P, 2018. 35-52.

Argues that Arnaud Lanusse, the editor of "Les Cenelles" and a freeborn native of New Orleans, does not fit into the image often assumed by modern commentators: "Of mixed race and proud of it, Lanusse ran at the highest levels of New Orleans colored society. He was a Confederate sympathizer at the start of the Civil War, served as principal of the city's only colored school, and owned more than ten slaves over the course of his life. He was not the model of 'free black' masses huddled between immovable walls of prejudice and race-based legislation that appears in many studies. He was, quite simply, an 'elite of his people'--educated, wealthy, and as respected as nearly any middle-class man of his time and place. But he, like . . . hundreds of others, felt the need to leave," as shown in his letters to "L'Union," "the city's increasingly radical French-language newspaper" (39). "Much like the Liberian 'pilgrims,' Lanusse sought citizenship of some sort, freedom from a legally-enforced second-class life" (39).

-

• Bruan, Juliane. “The Poetics of Education in Antebellum New Orleans.” "African American Literature in Transition, 1830-1850." Ed. Benjamin Fagan. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2021. 63-90. [Humanities Commons]

-

Humanities Commons

-

• Rabalais, Nathan. "L'identité dans la littérature franco-louisianaise: une troisième ère?" "Écrire pour gouverner, écrire pour contester." Ed. Jonathan Livernois. Laval: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 2021. 7-27.

"Le recueil de poésie collectif 'Les Cenelles' (1845), dont le titre fait référence à la couleur foncée d'un fruit indigène en Louisiane, fut le premier ouvrage de ce genre publié par les gens de couleur. Malheureusement, ce recueil étant écrit en français, il n'est pas reconnu institutionellement comme le premier ouvrage collectif afro-américain aux États-Unis. En outre, malgré plusieur traductions anglaises de ce texte, dont 'Creole Echoes' (2006) de Lynn Weiss et Norman Shapiro, ces poèmes demeurent également méconnus en études afro-américaines" (9).

Rabalais notes that while the poems in "Les Cenelles" embody "une sorte de romanticisme tardif" and "n'apparaissent guère engagés" (10), a more politically-inflected poetry appears, as noted by Caryn Cossé Bell (1997), in the French-language newspapers of the Civil War era, "L'Union" (1862-64) and "La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans" (1864-70): "La lutte pour l'égalité raciale s'exprime dans de nombreux poèmes écrits par Adolphe Duhart, Armand Lanusse, Joseph Mansion et Henri Louis Rey entre autres" (11).

-

See also

-

• Blassingame, John. "Black New Orleans: 1860-1880." Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1973. See pp. 17-19 for a discussion of "plaçage."

• Tregle, Joseph. "Creoles and Americans." "Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization." Ed. Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State UP, 1992. 131-41.

• Guillory, Monique. "Under One Roof: The Sins and Sanctity of the New Orleans Quadroon Balls." "Race Consciousness." Ed. Judith Jackson Fossett and Jeffrey A. Tucker. New York: New York UP, 1997. 80-89.

• Daut, Marlene L. "Before Harlem: The Franco-Haitian Grammar of Transnational African American Writing." "J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists" 3.2 (2015 Fall): 385-92.

Daut fills in some of the context in which Victor Séjour and other contributors to "Les Cenelles" lived and wrote.

-

Cited in

-

• Kinnamon 1997: 461.

-

Item Number

-

A0001

Title page (1845 ed.)

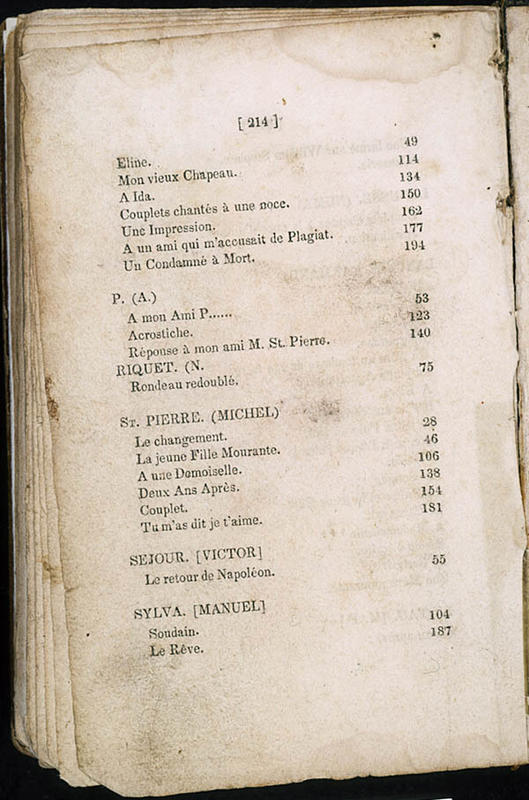

Title page (1845 ed.) Table of contents 1

Table of contents 1 Table of contents 2

Table of contents 2 Table of contents 3

Table of contents 3 Table of contents 4

Table of contents 4 Table of contents 5

Table of contents 5 Sample page image (p. 9, introduction)

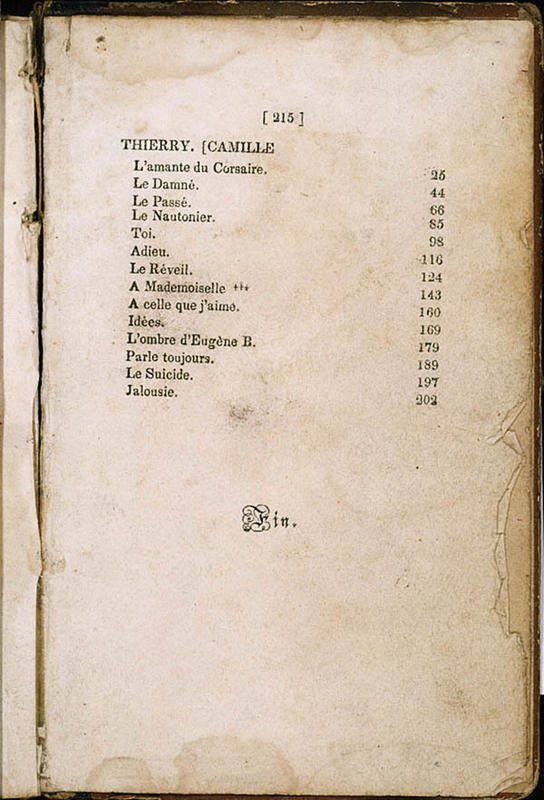

Sample page image (p. 9, introduction) Sample page image (p. 10, introduction)

Sample page image (p. 10, introduction) Sample page image (p. 11, introduction)

Sample page image (p. 11, introduction) Sample page image (p. 12, introduction)

Sample page image (p. 12, introduction) Sample page image (p. 13, introduction)

Sample page image (p. 13, introduction) Sample page image (p. 14, introduction)

Sample page image (p. 14, introduction) Sample page image (pp. 148-149)

Sample page image (pp. 148-149) Front cover and spine (1945 ed.)

Front cover and spine (1945 ed.) Title page (1979 trans.)

Title page (1979 trans.) Front cover (2003 ed.)

Front cover (2003 ed.)