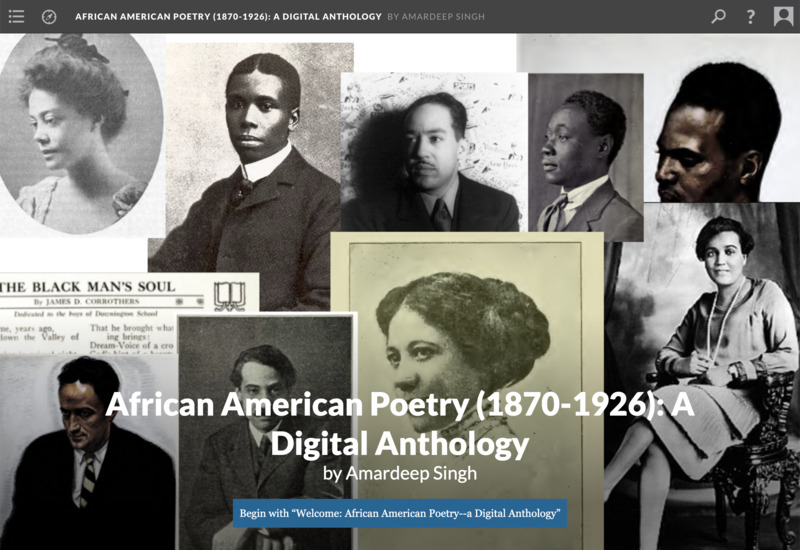

African American Poetry (1870-1926): A Digital Anthology

Item

-

Title

-

African American Poetry (1870-1926): A Digital Anthology

-

Commentary on anthology

-

The editor, Amardeep Singh (Lehigh University), offers some comments on his work on this digital anthology on his blog:

-

(11 August 2022):

Summer Research Journal: African American Poetry 1870-1926

This year I've been working on what's turned out to be a rather large and unwieldy digital archive project, something I'm calling an Anthology of African American Poetry, 1870-1926. I started the project back in early January, and I've spent a good chunk of the summer of 2022 working on it as well.

Why do this? First, I thought it might be useful to scholars and researchers to put all of these materials together in a single place. If you wanted to find all of the out-of-copyright poems you could by, say, Langston Hughes, it would be helpful to create a site where all of that is there and readily accessible.

Second, after years of creating simple digital editions of various works by specific African American writers, I had come to feel that simply producing a series of disconnected "digital editions" was not all that effective. What often happens is that already-established and widely anthologized authors -- people like Claude McKay or Langston Hughes -- might be rendered slightly more visible or accessible via quality digital editions. But these projects don't change the conversation about the bigger picture, and they don't do much to make more marginal voices visible. And there are so many worthwhile voices whose names barely register with readers today! From the mixed-race (African American + indigenous) writer Olivia Ward Bush-Banks, to the World War I veteran poet Lucian B. Watkins, to Georgia Douglas Johnson.

My theory is that creating a critical mass of texts, information about authors, and historical and contextual background information might just be able to start to shift the conversation in ways that might be interesting. On the one hand, I hope it might give certain names who have fallen out of literary history into new prominence. Analogously, collecting these materials under a single 'roof' might also help us understand better the contexts through which canonical figures emerged.

To give a simple example. Take the famous Countee Cullen poem "Heritage":

What is Africa to me:

Copper sun or scarlet sea,

Jungle star or jungle track,

Strong bronzed men, or regal black

Women from whose loins I sprang

When the birds of Eden sang?

One three centuries removed

From the scenes his fathers loved,

Spicy grove, cinnamon tree,

What is Africa to me? (continued here)

Cullen's poem is a powerful meditation on identity, specifically the sense of pain and absence he feels as a Black diasporic subject descended from people who had been enslaved and forcibly displaced from their homeland. He shares neither language nor culture nor religion with those ancestors: how, then, is he "African"?

Upon doing the kind of deep research I've been doing this year with this collection of poetry, I've come across many meditations along these lines from a broad array of African American poets. Some are Cullen's approximate peers (Langston Hughes, for example, wrote about the African ancestral past in poems like 'The Negro Speaks of Rivers' -- but he also actually visited West Africa in 1923 and later wrote some powerful meditations on that experience). Others are people who are today essentially unknown. See for instance Virginia P. Jackson's beautiful 1919 poem "Africa":

Often now I hear a voice a–calling,

Calling me across the mighty sea,

And responsively my heart is swelling,

Native land, I long to answer thee.

Long to leave the hate of foster mother,

To be nurtured by the kindly hand,

Sitting at thy feet with my black brother,

Africa! to know thy sunny land.

One thing we see as we look at this collection of "Africa" poems by African American poets like Jackson is that the majority of them are affirmative and celebratory ("I long to ... leave the hate of foster mother / To be nurtured by the kindly hand/ Sitting at thy feet with my black brother"). To my eye, only Cullen's poem seems to have this quality of alienation and questioning.

In effect, by looking at all of these poems together, I think we see the originality and thoughtfulness of Cullen's "Heritage." But perhaps, along the way, we might learn a little about Virginia P. Jackson or B.B. Church, poets that I presume the vast majority of readers will never have heard of before.

What even is this project? Is it an

Anthology or a

Textual Corpus or a

Digital Archive or

Something Else???

1. Is this an "anthology"? Or something else? Admittedly, the terms I've been using have been a little slippery -- the project is currently an anthology, but as a collection with more than fifty full books of poetry, four contemporaneous anthologies, and hundreds of poems published in periodicals, it's much bigger and inclusive than most anthologies. (Admittedly, the Norton Anthology of African American Literature is more than 2000 pages long, so perhaps it's not so far afield from that.)

2. Corpus? Many of the materials I've used came from a body of texts I have referred to as a corpus. This is a project I started two years ago, and discussed further here. For various reasons, people who do textual analysis of large corpora don't like it when you describe smaller collections of texts as a "corpus."

Still, one thing my collection has in common with a text corpus is that my criterion for inclusion is not necessarily 'quality' or the cultural capital of the authors. Rather, I'm looking to include anything that matches my demographic and historical criteria: any poetry authored by African American writers between 1870 and 1926. (Most anthology editors aim to select the cream of the crop in some way...)

3. Digital Archive? It could also be appropriate to simply refer to the collection as a digital archive of African American poetry from this period. The phrase "digital archive" has gone a bit out of fashion, as DH observers have been noting for several years. For one thing, there's been pushback from professional archivists about the misuse of the term "archive" to describe collections that are too small and too far removed from institutional frameworks for collecting and preserving documents. And indeed, this project is not really an 'institutional' project -- I am affiliated with a university and the project is being hosted on its servers, but as I've developed this project I've essentially been operating on my own, without official buy-in. Also, I am not collecting first-hand documents or even digitizing documents myself, but rather scouring various corners of the internet for versions (often page-image PDFs) that have been digitized by others but left, essentially hanging in limbo. My job has been to process those texts, make them easy to access and read and access, and to find various kinds of links between them, including ways of searching by author, periodical, theme and historical topic.

So if not "digital archive" and if not "corpus," maybe we'll just stay with "anthology." Below the fold, a bit more about the process I've used as I've continued to develop the project.

First, my job was to find materials. A good starting point was anthologies I had already known about, such as James Weldon Johnson's Book of American Negro Poetry (1922) and Alain Locke's The New Negro: an Interpretation (1925). Both are now out of copyright, and while there has been a perfectly fine version of the Johnson anthology on Project Gutenberg, I hadn't seen a very good version of the Locke anthology online as of January 2022. I made one, here.

I also knew that Langston Hughes's The Weary Blues, Countee Cullen's Color, and Fire!! Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists were all recently out of copyright. So I tracked down page image versions of these & made simple digital editions of these works as well.

I also used materials developed for earlier projects, including Claude McKay's Early Poetry and Women of the Early Harlem Renaissance.

And as I've learned about other materials, like the Dunbar Entertainer (1920), the Brownies' Book (1920-1921), and as my knowledge of African American periodicals from the period has improved I've continued to look for materials in other nooks and crannies.

I've also been reading a fair bit to improve my knowledge of the period. This summer I read Langston Hughes memoir, The Big Sea: an Autobiography, and Arnold Rampersad's 1986 biography of Hughes.

I had already read Wayne Cooper's biography of Claude McKay, but I went ahead and re-read chapters relating to McKay's incredibly tumultuous life in the 1910s and 20s.

(Side note: Hughes and McKay were both inveterate travelers -- nomads, even -- who spent time in Europe as well as the Soviet Union. Surprisingly, though their paths nearly intersected a couple of times, I don't think they directly met each other in the early 1920s).

Another incredibly helpful biography is David Levering Lewis' massive biography of W.E.B. Du Bois. As the editor of The Crisis, Du Bois was directly involved in publishing quite a lot of African American poetry (more than 250 poems were published in The Crisis between 1910 and 1926). And the poetry contests in The Crisis in 1925-7 helped to solidify the reputations of emerging stars like Hughes and Cullen. (It's not an accident that Du Bois' daughter married one of those emerging stars in 1927!)

Interestingly, I don't think there are biographies of a few other key figures in the orbit of Du Bois, Hughes, and McKay. For instance, I've never seen biographies of Jessie Redmon Fauset (someone did a dissertation on her back in 1976, but it was never published as a book) or Georgia Douglas Johnson!

Georgia Douglas Johnson in particular seems worth considering as a subject for a possible biography... She was one of the most prolific contributors to The Crisis through the 1910s and 20s, was widely anthologized at the time, and was very, very well connected to a network of Black writers through her "S Street Salon" in Washington, DC.

Next steps. As of August 2022, the project is getting close to critical mass, though there's obviously much more to be done to find ways to make the materials easier to access and more useful, especially to students and teachers.

But the most substantial new work will probably happen in January 2023, when the anthology Caroling Dusk comes out of copyright (as does James Weldon Johnson's God's Trombones and Langston Hughes' Fine Clothes to the Jew). I anticipate creating new pages for those books at the time, and continuing to expand the project a little each year with new materials as they become available.

-

https://www.electrostani.com/2022/08/summer-research-journal-african.html

-

See also

-

Singh, Amardeep. "Visualizing the Uplift: Digitizing Poetry by African American Women, 1900-1922." "Feminist Modernist Studies" 1.3 (2018): 269-81.

-

Item Number

-

A0572

Front cover

Front cover