-

Title

-

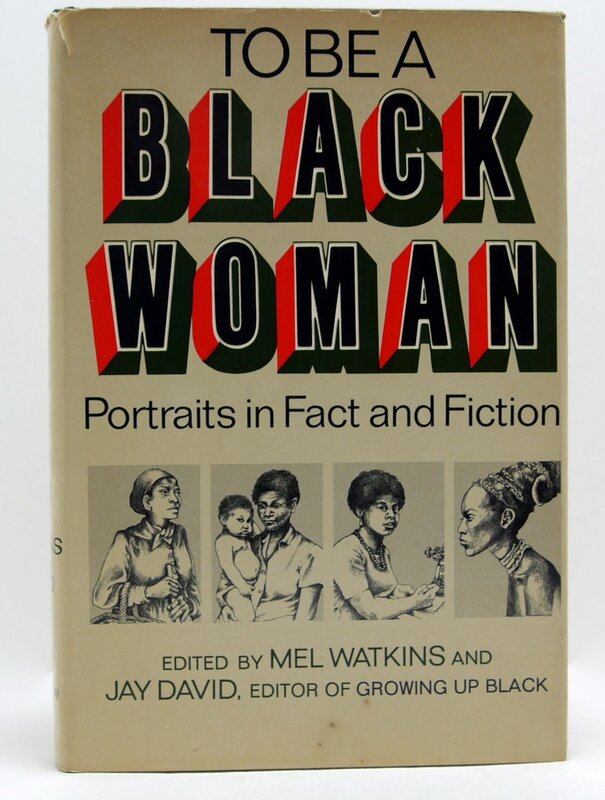

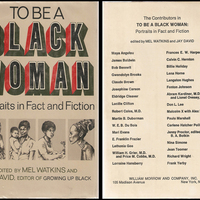

To Be a Black Woman: Portraits in Fact and Fiction

-

This edition

-

"To Be a Black Woman: Portraits in Fact and Fiction". Ed. Mel Watkins and Jay David. New York: William Morrow, 1970.

-

Table of contents

-

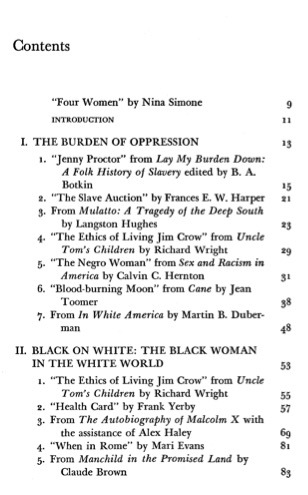

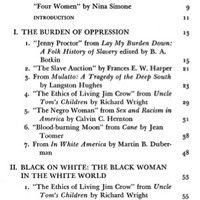

● Nina Simone / Four Women (9)

● Mel Watkins and Jay David / Introduction (11)

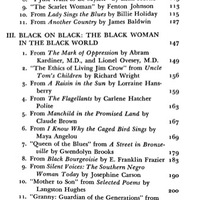

I. The Burden of Oppression (13)

● Jenny Proctor / The Narrative of Jenny Proctor (from "Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery," ed. B. A. Botkin) (15)

● Frances E. W. Harper / The Slave Auction (21)

● Langston Hughes / "Mulatto: A Tragedy of the Deep South" (excerpt) (23)

● Richard Wright / The Ethics of Living Jim Crow (excerpt) (from "Uncle Tom's Children") (29)

● Calvin C. Herton / The Negro Woman (from "Sex and Racism in America") (31)

● Jean Toomer / Blood-burning Moon (from "Cane") (38)

● Martin B. Duberman / "In White America" (excerpt) (48)

II. Black on White: The Black Woman in the White World (53)

● Richard Wright / The Ethics of LIving Jim Crow (excerpt) (from "Uncle Tom's Children") (55)

● Frank Yerby / Health Card (57)

● Alex Haley / "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" (excerpt) (69)

● Mari Evans / When in Rome (81)

● Claude Brown / "Manchild in the Promised Land" (excerpt) (83)

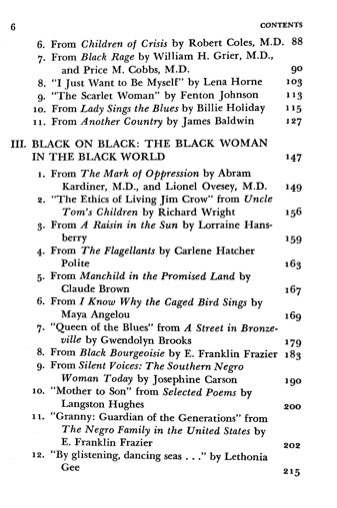

● Robert Coles / "Children of Crisis" (excerpt) (88)

● William H. Grier and Price M. Cobbs / "Black Rage" (excerpt) (90)

● Lena Horne / I Just Want to Be Myself (103)

● Fenton Johnson / The Scarlet Woman (113)

● Billie Holiday / "Lady Sings the Blues" (excerpt) (115)

● James Baldwin / "Another Country" (excerpt) (127)

III. Black on Black: The Black Woman in the Black World (147)

● Abram Kardiner and Lionel Ovesy / "The Mark of Oppression" (excerpt) (149)

● Richard Wright / The Ethics of Living Jim Crow (excerpt) (from "Uncle Tom's Children") (156)

● Lorraine Hansberry / "A Raisin in the Sun" (excerpt) (159)

● Carlene Hatcher Polite / "The Flagellants" (excerpt) (163)

● Claude Brown / "Manchild in the Promised Land" (excerpt) (167)

● Maya Angelou / "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings" (excerpt) (169)

● Gwendolyn Brooks / Queen of the Blues (from "A Street in Bronzeville") (179)

● E. Franklin Frazier / "Black Bourgeoisie" (excerpt) (183)

● Josephine Carson / "Silent Voices: The Southern Negro Woman Today" (excerpt) (190)

● Langston Hughes / Mother to Son (from "Selected Poems") (200)

● E. Franklin Frazier / Granny: Guardian of the Generations (from "The Negro Family in the United States") (202)

● Lethonia Gee / By glistening dancing seas . . . (215)

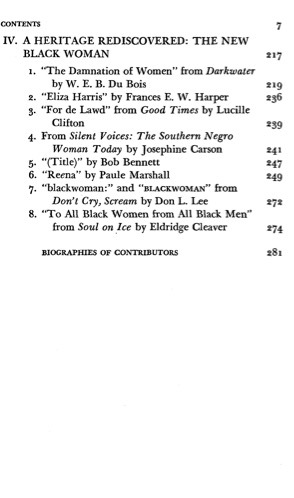

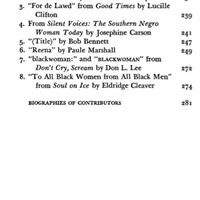

IV. A Heritage Rediscovered: The New Black Woman (217)

● W. E. B. Du Bois / The Damnation of Women (from "Darkwater") (219)

● Frances E. W. Harper / Eliza Harris (236)

● Lucille Clifton / For de Lawd (from "Good Times") (239)

● Josephine Carson / "Silent Voices: The Southern Negro Woman Today" (excerpt) (241)

● Bob Bennett / (Title) (247)

● Paule Marshall / Reena (249)

● Don L. Lee / blackwoman: and BLACKWOMAN (from "Don't Cry, Scream") (272)

● Eldridge Cleaver / To All Black Women from All Black Men (from "Soul on Ice") (274)

Biographies of Contributors (281)

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

● Cole, Johnneta B. "Black Women in America: An Annotated Bibliography." "The Black Scholar" 3.4 (1971): 42-53.

The annotation for "To Be a Black Woman" reads: "Portraits of the experiences of joy as well as oppression of black women. A varied collection which includes articles such as 'The Negro Woman' by Hernton, poems by Nina Simone, Don L. Lee and others, and passages from James Baldwin, Lena Horne, Gwendolyn Brooks and others" (52).

-

● "Books Received." "Black World" (Jan. 1972): 96.

"Contains 39 selections that 'range from sociological studies and essays to the intense personal depiction offered by autobiographies, poetry and fiction.' Of the 12 Black women included, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, Carlene Polite, Lorraine Hansberry, Maya Angelou and Paule Marshall are represented by prose. Mel Watkins is a young editor of the New York Times Book Review" (96).

-

● Morrison, Toni. Review of "To Be a Black Woman." "New York Times" 28 March 1971: BR8.

Morrison offers a scathing review of the anthology, arguing that the editors' discourse in the anthology succeeds in confirming, rather than "disassembling" myths about black women: "Anthologists do not 'write' their books, but they are responsible for them. No less than the authors they choose to reprint, they reveal the fabric of their ideas and the borders of their intelligence. In this collection the fabric is worn and the borders fixed. . . . With the kindest words, the sweetest euphemisms, the commonest sociological jargon, their 'Portraits in Fact and Fiction' manages to remain fiction. We are left at the end with the same labels provided in the beginning: 'laborer,' 'breadwinner,' 'sexual myth incarnate—plaything,' 'protector,' 'provider,' 'cushion.' In spite of the inclusion of a few splendid pieces, no recognizable human being emerges. What does emerge is an oppressed but sexy, sexy but emasculating, bitch. . . . ignoring some of their own selections and hundreds of years of evidence to the contrary, they are not embarrassed to write, 'Finally, in the past decade she has become deeply involved in the black man's fight for equal rights.' Finally? Past decade? Black man's fight? . . . Editorial comment is not the only malignancy of the book. Of the 39 selections, less than a third are by women. The “factual” pieces include the facile generalizations of Calvin C. Hernton, and the racist scholarship of Abram Kardiner and Lionel Ovesey who, along with the editors, speak of families without live‐in fathers as 'broken.' The fiction contains an extremely fraudulent monologue in Langston Hughes's ill‐conceived play, 'The Mulatto,' and some well‐intentioned but slovenly verse by Fenton Johnson and Francis E. W. Harper. . . . Somewhere there is, or will be, an in‐depth portrait of the black woman. At the moment, it resides outside the pages of this book. She is somewhere, though, some place, just as she always has been, up to her pelvis in myth, asking those sad, sad questions: When I was brave, was it only because I was masculine? When I was human, was it only because I was passive? When I survived, was it only because my man was dead? And when ship loads of slaves became a race of 30 million was that really only because I was fecund? "

-

Commentary on anthology

-

● "Personality: Vanessa Myers Mason." "Richmond Free Press" 19 April 2019. Web.

This profile of Vanessa Myers Mason, founder of the nonprofit MOMs (Missing Our Moms) Inc. includes a questionnaire filled out by Mason: "Books that influenced me the most": "'To Be a Black Woman: Portraits in Fact and Fiction,' edited by Mel Watkins and Jay David."

-

Richmond Free Press

-

Cited in

-

● not in Kinnamon 1997

-

Item Number

-

A0137