-

Title

-

Upward Path: A Reader for Colored Children

-

This edition

-

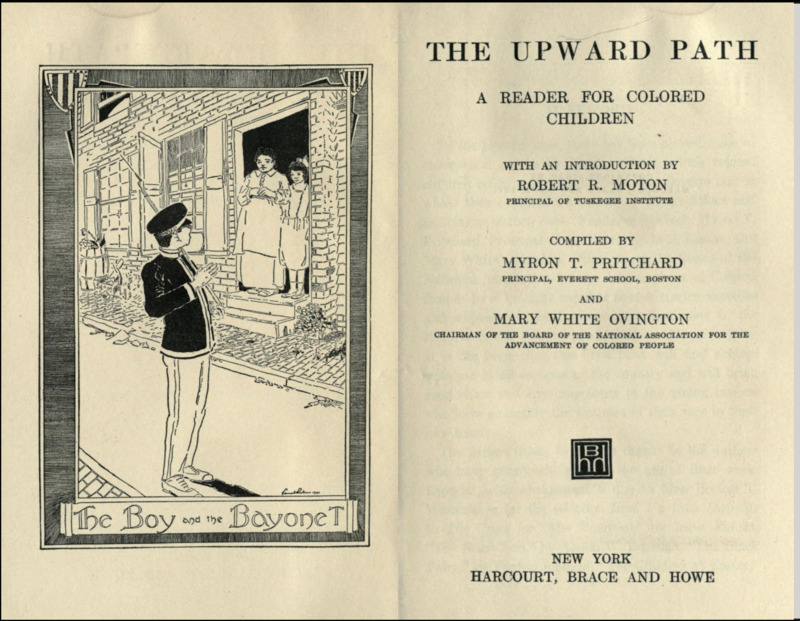

"The Upward Path: A Reader for Colored Children." Ed. Myron T. Pritchard and Mary White Ovington. Intro. Robert R. Moton. Illus. Laura Wheeler. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920. xi+255 pp.

-

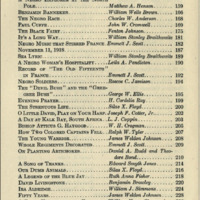

Table of contents

-

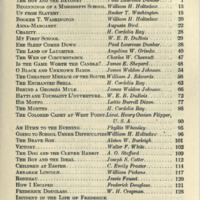

● [Foreword] (v-vi)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / The Boy and the Bayonet [short story] (1-12)

● William H. Holtzclaw / Beginnings of a Mississippi School [nonfiction] (13-14)

● Booker T. Washington / [from] “Up from Slavery”: The Struggle for an Education [memoir] (15-20)

● William H. Holtzclaw / Booker T. Washington: A Student’s Memory of Him [nonfiction] (20-22)

● Augusta Bird / Anna-Margaret [short story] (22-28)

● H. Cordelia Ray / Charity [“I saw a maiden, fairest of the fair”] [poem, 4-lines] (28)

● W. E. B. DuBois / My First School [from “The Souls of Black Folk”] [nonfiction] (29-38)

● Paul Laurence Dunbar / Ere Sleep Comes Down to Soothe the Weary Eyes [= first line] [poem] (38-40)

● Angelina W. Grimke / The Land of Laughter [short story] (40-47)

● Charles W. Chesnutt / The Web of Circumstance [nonfiction, one paragraph] (47)

● James E. Shepherd / Is the Game Worth the Candle? [essay] (48-53)

● James Weldon Johnson / O Black and Unknown Bards [“O black and unknown bards of long ago”] (54-55)

● William J. Edwards / The Greatest Menace of the South [nonfiction] (56-62)

● H. Cordelia Ray / The Enchanted Shell [“Fair, fragile Una, golden-haired”] [poem] (63-65)

● James Weldon Johnson / Behind a Georgia Mule [short story] (66-72)

● W. E. B. DuBois / Hayti and Toussaint L'Ouverture [nonfiction] (72-77)

● Lottie Burrell Dixon / His Motto [short story] (77-85) [from The Crisis]

● H. Cordelia Ray / The Months [“To herald in another year”] [poem] (86-89)

● Lieut. Henry Ossian Flipper, USA / The Colored Cadet at West Point [nonfiction] (90-94)

● Phyllis Wheatley / An Hymn to the Evening [“Soon as the sun forsook the eastern main”] [poem] (95)

● William H. Holtzclaw / Going to School Under Difficulties [nonfiction] (96-101)

● Alston W. Burleigh / The Brave Son [“A little boy, lost in his childish play”] [poem] (101) [from The Crisis]

● Walter F. White / Victory [short story] (102-09)

● A. O. Stafford / The Dog and the Clever Rabbit [short story] (109-12) [from Stafford’s Animal Tales]

● Joseph S. Cotter / The Boy and the Ideal [short story] (112-14)

● C. Emily Frazier / Children at Easter [“That day in old Jerusalem when Christ our Lord was slain”] [poem] (114-16) [from The Crisis]

● William Pickens / Abraham Lincoln [nonfiction] (117-20)

● Jessie Fauset / Rondeau [“When April’s here and meadows wide”] [poem] (120) [from The Crisis]

● Frederick Douglass / How I Escaped [nonfiction] (121-28)

● W. H. Crogman / Frederick Douglass [nonfiction] (128-33)

● [Frederick Douglass] / Incident in the Life of Frederick Douglass [an incident from his life that Douglass recounted “to the pupils of a colored school in Talbot County, Maryland, the county in which he was born”] [nonfiction] (134-35)

● William Henry Sheppard / Animal Life in the Congo [nonfiction] (135-42)

● Lillian B. Witten / Coöperation and the Latin Class [short story] (143-47)

● Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. [name given as “Joseph F. Cotter, Jr.” in ToC] / The Band of Gideon [“The Band of Gideon roam the sky”] [poem] (148-49)

● Azalia Hackley / The Home of the Colored Girl Beautiful [nonfiction] (150-52)

● Lillian B. Witten / Knighting of Donald [short story] (153-58)

● Matthew A. Henson / A Negro Explorer at the North Pole [nonfiction] (159-65)

● William Wells Brown / Benjamin Banneker [nonfiction] (166-68)

● Charles W. Anderson / The Negro Race [nonfiction, one paragraph] (168)

● John W. Cromwell / Paul Cuffe [nonfiction] (169-75)

● Fenton Johnson / The Black Fairy [short story] (175-81) [from The Crisis]

● William Stanley Braithwaite / It's a Long Way [“It’s a long way the sea-winds blow”] [poem] (181-82)

● Emmett J. Scott / Negro Music that Stirred France [nonfiction] (182-87)

● Anon. (“Jesse,” “a young first lieutenant (colored) in the 366th Infantry, Company L, 92nd Division, Cleveland, Ohio”) / November 11, 1918 [letter] (187-88)

● William Stanley Braithwaite / Sea Lyric [“Over the seas to-night, love”] [poem] (189)

● Leila A. Pendleton / A Negro Woman's Hospitality [nonfiction] (190-92)

● Emmett J. Scott / Record of "The Old Fifteenth" in France [nonfiction] (192-93)

● Roscoe C. Jamison / Negro Soldiers [“These truly are the Brave”] [poem] (194) [from The Crisis]

● George W. Ellis / The "Devil Bush" and the "Greegree Bush" [nonfiction] (195-98)

● H. Cordelia Ray / Evening Prayer [“Father of Love!”] [poem] (199)

● Silas X. Floyd / Strenuous Life [short story] (200-02)

● Joseph S. Cotter, Jr. [name given as “Joseph F. Cotter, Jr.”] / O Little David, Play on Your Harp [= first line] (202)

● L. J. Coppin / A Day at Kalk Bay, South Africa [nonfiction] (203-05)

● W. H. Crogman / Bishop Atticus G. Haygood [nonfiction] (205-06)

● Ralph W. Tyler / How Two Colored Captains Fell [nonfiction] (207-08)

● James Weldon Johnson / The Young Warrior [“Mother, shed no mournful tears”] [poem] (208-09)

● Emmett J. Scott / Whole Regiments Decorated [nonfiction, one paragraph] (209)

● Daniel A. Rudd and Theodore Bond / On Planting Artichokes [from “The Life of Scott Bond”] [nonfiction] (210-14)

● Edward Smyth Jones / A Song of Thanks [“For the sun that shone at the dawn of spring”] [poem] (214-16)

● Silas X. Floyd / Our Dumb Animals [nonfiction] (216-17)

● Ruth Anna Fisher / A Legend of the Blue Jay [short story] (218-20) [from The Crisis]

● Benjamin Brawley / David Livingstone [nonfiction] (220-23)

● William J. Simmons / Ira Aldridge [nonfiction] (224-28)

● James Weldon Johnson / Fifty Years (1863-1913) [“O brothers mine, to-day we stand”] [poem] (228-32)

● William Henry Sheppard / A Great Kingdom in the Congo [nonfiction] (233-49)

● William C. Jason / Pillars of the State [nonfiction, one paragraph] (249)

● Kelly Miller / Oath of Afro-American Youth [nonfiction] (250)

● Notes [on authors] (251-55)

-

About the anthology

-

● Mary White Ovington (1865-1951) was a white activist who became involved in the civil rights movement after hearing Frederick Douglass speak in 1890. She became one of the founders of the NAACP in 1909, and its executive secretary. At the time of this anthology, she was Chairman of the Board of the NAACP (v). She was also involved in the women's suffrage and pacifism movements. She retired from the NAACP in 1947 at age 82 after almost four decades of work with the organization.

A fuller biography is available online in the "Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography."

-

Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

-

● Myron T. Pritchard (1853-1935) was principal of the Everett School, Boston (v). He co-edited a number of anthologies designed for children or students, such as "Stories of Thrift for Young Americans" (1915) and "Lessons in Citizenship for the Junior High School and the Upper Grades" (1928).

-

● Laura Wheeler (later, Waring) (1887-1948) is not credited explicitly as the illustrator in this volume. However, Theresa Leininger-Miller (in "'A Constant Stimulus and Inspiration': Laura Wheeler Waring in Paris in the 1910s and 1920s," "Notes in the History of Art" 24.4 [2005]: 13-23) states that: "Waring's jacket designs include those for two books by Mary White Ovington published by Harcourt—"The Shadow" (1916) and "The Upward Path: A Reader for Colored Children" (1920); H. Cordelia Ray's "The Enchanted Shell" (1920); Paul Laurence Dunbar's "Boy and the Bayonet" (date unknown); and "The Dog and the Clever Rabbit" (author and date unknown). The last two are listed in Murphy's entry on Waring in "St. James Guide"" (22n.17) and there is extensive discussion of Wheeler's career as an illustrator during the Harlem Renaissance era, including for this volume, in Caroline Goeser, "Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity" (Lawrence: UP of Kansas, 2007), esp. 119-20. For more on Laura Wheeler Waring, see "In Memoriam: Laura Wheeler Waring 1887-1948: An Exhibition of Paintings" (Washington, DC: Howard University, Gallery of Art, 1949).

The full-page illustrations in "The Upward Path" consist of "The Boy and the Bayonet" (the frontispiece: this corresponds to one of the items listed by Leininger-Miller); "The Land of Laughter" (43); "The Enchanted Shell" (64); "His Motto" (81); "Children at Easter" (115); and "The Black Fairy" (177). Each of these illustrations carries the same signature: it is mostly not clearly legible, but on p. 64 it clearly reads "Laura Wheeler"; the date is less clear but seems to be "1920" (as on the frontispiece as well, where the date is clearer). (No date seems to accompany the signature to the illustration on p. 177.)

The inset illustrations on pp. 27 (for "Anna-Margaret"), 99 (for "Going to School under Difficulties"), 111 (for "The Dog and the Clever Rabbit": see Leininger-Miller above), 158 (for "The Knighting of Donald") seem to carry the same signature as the full-page illustrations, but without a date. The inset illustrations on pp. 195, 196, 197, 198 (x2) (for "The 'Devil Bush' and the 'Greegree Bush'") seem to carry initials and abbreviated date: "LW 20."

Caroline Goeser notes that, "As none of her drawings [in this volume] carried specific captions, restrictively incorporating a line from the text, Wheeler was free to interpret the short stories creatively" (120).

-

Anthology editor(s)' discourse

-

● "To the present time, there has been no collection of stories and poems by Negro writers, which colored children could read with interest and pleasure and in which they could find a mirror of the traditions and aspirations of their race. Realizing this lack, [the editors] have brought together poems, stories, sketches and addresses which bear eloquent testimony to the richness of the literary product of our Negro writers. It is the hope that this little book will find a large welcome in all sections of the country and will bring good cheer and encouragement to the young readers who have so largely the fortunes of their race in their own hands" (v).

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

● Review of "The Upward Path." "Southern Workman" 49.11 (Nov. 1920): 530.

"As an experiment in a hitherto unworked field, 'The Upward Path' will make a strong appeal to teachers in colored schools who have long felt the need of a reader showing the achievements of members of the race they are endeavoring to inspire with race pride. So much is done in magazines, histories, plays, and moving-picture shows to caricature the Negro, and so much that he reads, sees, and studies relates to white people, as though they only had done admirable things, that there is great need of books like 'The Upward Path' to give colored young people a chance to know something of the literature, aspirations, and achievements of their own race.

"Dr. Moton in his introduction emphasizes this fact and refers to the gratifying results which have followed the introduction of classes in Negro history into various colored schools. There is possibly too much of narrative in the selections and too little of suitable material for school declamation. The choice of poetry is excellent and the biographical 'Notes' of authors at the end of the volume are most valuable. The reader is suitable for seventh- and eighth-grade pupils." [full text of review]

-

Google Books

-

Commentary on anthology

-

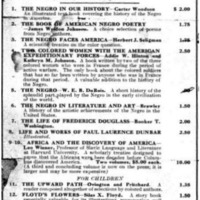

● "The Upward Path" was included among the twelve or fifteen books promoted by Kathryn M. Johnson as the "Two-Foot Shelf of Negro Literature" in the 1920s: Johnson "worked as a roving salesperson for the Associated Publishers, the book-publishing firm of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, founded by [Carter] Woodson in 1915 and located then, as now, in Washington. In particular, she toured the nation selling what she called her 'Two-Foot Shelf of Negro Literature,' consisting of fifteen books issued by the association [the books were originally published by a variety of publishers, but they may have been re-issued by Associated Publishers]. Her purpose was to offset 'the silence of our educational system regarding twelve million American citizens'; reading these books, she added, 'will increase your respect for the Negro race'" ("The Correspondence of W.E.B. Du Bois," Vol. 1, "Selections, 1877-1934." Ed. Herbert Aptheker. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1973. 334). The only other anthology included in this "Two-Foot Shelf" as advertised in the 1920s (see image) was James Weldon Johnson's "The Book of American Negro Poetry" (1922), although the collection also includes Benjamin Brawley's "The Negro in Literature and Art," Silas X. Floyd's "Floyd's Flowers: or, Duty and Beauty for Colored Children; Being one hundred short stories" (1905) and a volume titled "Life and Works of Paul Laurence Dunbar."

This advertisement only lists 12 volumes in the collection, and Johnson's letterhead for the "Two-Foot Shelf of Negro Literature" likewise features an image of twelve uniform volumes (perhaps a stock image), but the text on the letterhead says: "Composed of 15 books selected with care and discrimination, for the purpose of offsetting the silence of our educational system regarding twelve million American citizens. Add these volumes to your library. Reading them will increase your respect for the Negro race."

Johnson's inclusion of "The Upward Path" in her "Two-Foot Library" may reflect, in part, the connection between herself and Mary White Ovington: Ovington wrote a short piece on Kathryn Johnson's itinerant bookselling as "Selling Race Pride," in "Publishers' Weekly" (Jan. 1925) and the two women had known each other since Johnson joined the NAACP in 1912 (Jane Greenway Carr. "'We Must Seek on the Highways the Unconverted': Kathryn Magnolia Johnson and Literary Activism on the Road." "American Quarterly" 67.2 [2015]: 443-70, at 443).

Ovington's Jan. 1925 piece states that by 1925, Johnson "had covered ten states and twenty-five thousand miles, selling five thousand volumes"; Johnson's own manuscript autobiography says simply that she put "'several thousand copies of different books' into the hands of African American readers" (Carr 2015: 444). Johnson had purchased a Ford and could fit one hundred volumes in the car's backseat, Carr tells us, so that was the limit on the size of her stock for each bookselling trip (Carr 2015: 459). Johnson speaks of "touring the country for four years in a Ford coupé, carrying with me a two-foot shelf of Negro literature in the hope of doing something to offset the silence of the textbooks with regard to the achievements of the colored people" (quoted in Emory S. Bogardus, "Immigration and Race Attitudes" [D.C. Heath, 1928], 246; see also Bruno Lasker, "Race Attitudes in Children" [New York: Henry Holt, 1929], 160).

In an article on "Educating Nordics" ("The Messenger: New Opinion of the Negro" vol. 9 [1 May 1927]: 144, 169), Johnson elaborates more fully: "There is no doubt of the great need of the education of the white people through the distribution of literature concerning the Negro. . . . That a white man could grow up in the South, or in any other section of the country, and learn nothing about Negroes except that they have been slaves, is not a thing to amaze any one; but the tragic thing about the whole matter is that not even Negroes have had a chance to learn anything of themselves, until within the last few years.

"During the time that I was traveling as field worker for the N.A.A.C.P., I began to realize as never before the need of a definite tangible effort to help relieve this situation. . . . This realization of a need grew into a compelling desire to somehow reach the people with a message that would awaken them to the injustice that had been done hem: and so for five years I have been driving over the country, devoting myself to the task of getting into the hands of the people a Two-Foot Shelf of Negro Literature. This work has been done solely through public addresses, with the hope that I would not only be able to put some books into their hands, but so inspire them that they would have a desire to read them after they had purchased them. This has been an arduous task, fraught with no little difficulty, and sometimes danger, for we have not only driven north, east, and west, but even into the far south, through Alabama, Georgia and along the east and west coasts of Florida, leaving our car at Miami, and going by overseas railroad as far south as Key West.

"Everywhere we have found to a greater or less degree an awakening consciousness among our people, and in some places their response has been gratifying to the greatest degree. I have been able to place into their hands several thousand copies of different books, all of which were selected with the desire of offsetting the silence of text books and other books regarding the achievements of colored people.

"In much the same way that this had been done among colored people, I think it could be done among the white. My method has been to talk to ready made audiences, for the reason that I have not been able to make out a set program for myself. Upon getting into a city I would ascertain the number of colored churches, and how many had congregations with a fair degree of intelligence. I would then visit the churches on Sunday, and talk for ten or fifteen minutes at the close of the services, according to the good nature and interest of the pastor in charge. I have also addressed Insurance Societies, Women's Clubs, Conferences, Conventions and what not.

"Working in this way I have been forced to stay in some cities like Washington, Philadelphia, and Chicago, from six weeks to three months. Even at this rate I have been able to reach only a small minority of the people" (144).

Johnson notes that sometimes, through the work of local residents, it was possible to get the "Two-Foot Shelf" (total cost $25) purchased for the local public library, as occurred in Danville, Illinois, and in Evanston, Illinois (144). So, too, she was able to sell a set to the library of the University of Kansas in Lawrence, Kansas (144). Johnson's own efforts saw a number of books from the "Two-Foot Shelf" acquired for the public libraries in St. Louis and in Gary, Indiana (144). On the other hand, middle-class black families--who might have been able to purchase the set for themselves--"would [as she found in Louisville] frequently hide behind the statement that they had them in . . . their branch libraries, when the truth of the matter was that there were only two copies in each of them, which when distributed would make about one copy for about ten or fifteen thousand people. The result was that the people were generally ignorant about their own racial accomplishments" (144).

Johnson calls for the creation of "a Bureau for the Distribution of Negro Literature, properly financed, until it can be made to support itself" (144).

Kathryn Johnson's "Two-Foot Shelf of Negro Literature" was modeled on the Harvard Classics, the "Five Foot Shelf" of world classics edited by Harvard president Charles W. Eliot and Professor William A. Neilson and first published in 1909 (Carr 2015: 453). Johnson observed that the Harvard Classics were "selling well" and decided to market her own collection of "Negro Literature" on this model (Carr 2015: 453). As with Eliot, Johnson's motivation was not primarily commercial but rather "educational": her aim was for "the Negro to understand his honorable place in the United States" (quoted in Carr 2015: 454)--and echoes the aim of many of the anthologists of African American writing, including the editors of "The Upward Path."

-

Item Number

-

A0506

Golden Slippers: An Anthology of Negro Poetry for Young Readers

Golden Slippers: An Anthology of Negro Poetry for Young Readers