-

Title

-

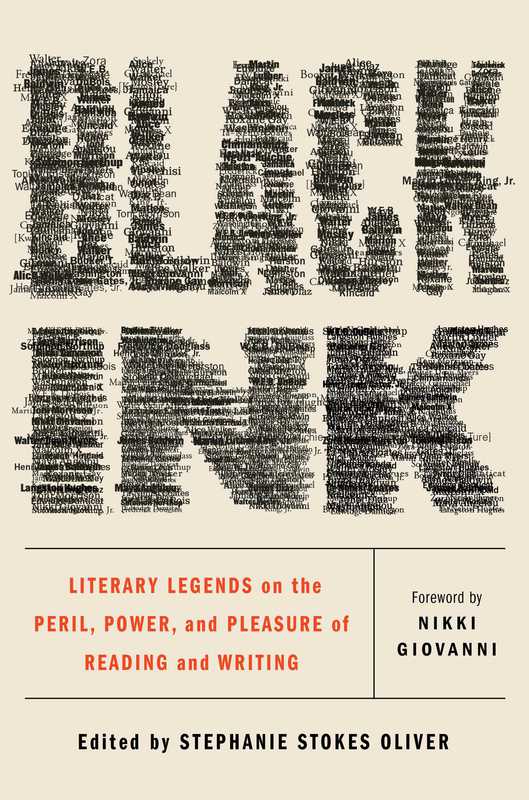

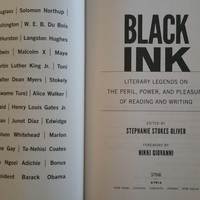

Black Ink: Literary Legends on the Peril, Power, and Pleasure of Reading and Writing

-

This edition

-

"Black Ink: Literary Legends on the Peril, Power, and Pleasure of Reading and Writing." Ed. Stephanie Stokes Oliver. Foreword Nikki Giovanni. New York: 37Ink / Atria, 2018. xxiv+244 pp.

-

Table of contents

-

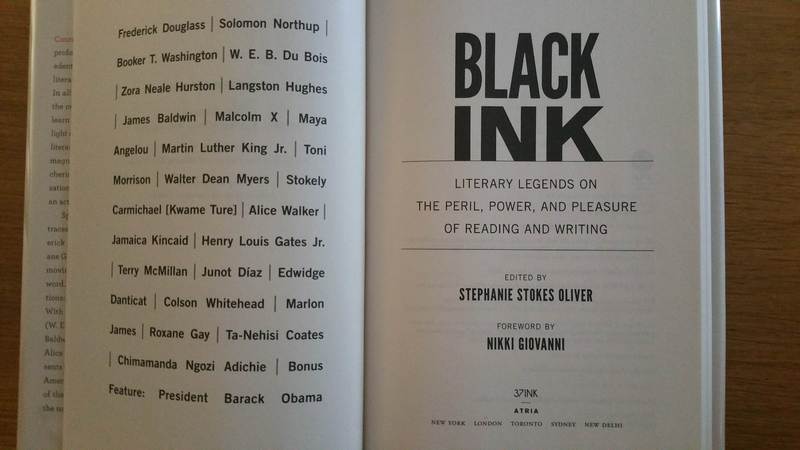

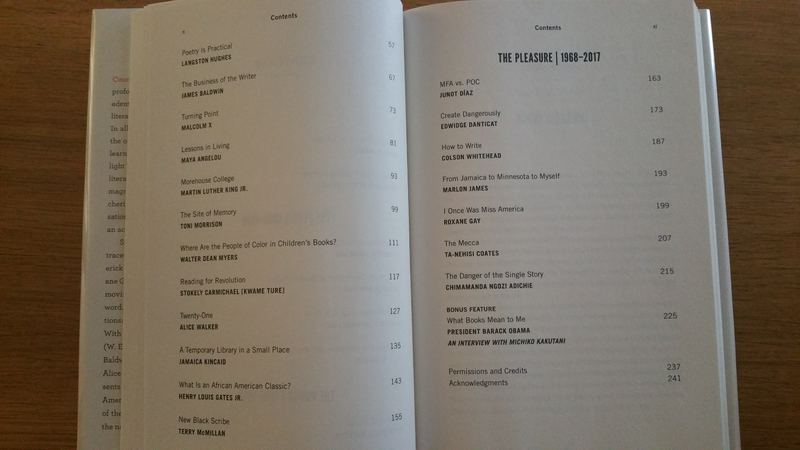

● Nikki Giovanni / Foreword: Our First Stories

● Stephanie Stokes Oliver / Introduction: Reading Matters

The Peril: 1800-1900

● Frederick Douglass / Suspected of Having a Book

● Solomon Northrup / Nine Years Deprived of a Sheet of Paper

● Booker T. Washington / A Whole Race Begins to Read

● W. E. B. Du Bois / The Negro in Literature and Art

The Power: 1900-1968

● Zora Neale Hurston / Books and Things

● Langston Hughes / Poetry Is Practical

● James Baldwin / The Business of the Writer

● Malcolm X / Turning Point

● Maya Angelou / Lessons in Living

● Martin Luther King, Jr. / Morehouse College

● Toni Morrison / The Site of Memory

● Walter Dean Myers / Where Are the People of Color in Children's Books?

● Stokely Carmichael [Kwame Ture] / Reading for Revolution

● Alice Walker / Twenty-One

● Jamaica Kincaid / A Temporary Library in a Small Place

● Henry Louis Gates, Jr. / What Is an African American Classic?

● Terry McMillan / The New Black Scribe

The Pleasure: 1968-2017

● Junot Diaz / MFA vs. POC

● Edwidge Danticat / Create Dangerously

● Colson Whitehead / How to Write

● Marlon James / From Jamaica to Minnesota to Myself

● Roxane Gay / I Once Was Miss America

● Ta-Nehisi Coates / The Mecca

● Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie / The Danger of the Single Story

● President Barack Obama interviewed by Michiko Kakutani / What Books Mean to Me

-

About the anthology

-

● Includes 25 selections, in addition to the introduction and foreword.

● The table of contents listed in WorldCat curiously includes an item (Walter Mosley, "Patter and Patois" from "New York Times" 3 Aug. 2015) that does not actually appear in the anthology--and it omits a piece that does appear (Colson Whitehead, "How to Write"). Perhaps there was a switch about which item was to be included at a late stage?

● So, too, the final item, as indicated in the table of contents given in WorldCat is a poem by the poet and spoken word performer J. Ivy [James Ivy Richardson II] ("I Need to Write . . ."); in fact, the volume's contents conclude with a "bonus feature": an interview of Barack Obama by Michiko Kakutani. Again, perhaps this discrepancy reflects a late editorial decision?

● Sources and handling of copy texts: Sources of texts are indicated under "Permissions and Credits" (237-40), but this simply indicates title of the source work and permission holder, without giving specific edition information, and there is no textual note indicating how the copy texts are handled. The introduction notes that "some of the selections from book-length works were meticulously condensed" (xxiii). (Unclear whether this simply means they were excerpted without alteration or were "condensed" in some fashion.)

● Arrangement of selections: Selections are arranged in three chronological periods labelled as follows: The peril 1800-1900; The power 1900-1968; The pleasure 1968-2017. "The order of the pieces is chronological from the birth of each writer, with the exception of Frederick Douglass, who was born after Solomon Northup, but because his memoir was published first . . . we have put his story in the lead" (xxiii).

● Apparatus provided by editor(s): a biographical headnote (1/2 to 1 whole page in length) about the author accompanies each selection, but there is otherwise no annotation or glossing of the selections, nor any references to other scholarship (although some of each author's works are typically mentioned in the biographical headnote).

● Nikki Giovanni's introduction and many of the reviews of this anthology assume that the excerpts collected argue not only for the importance of reading and writing in the lives and for the well-being of African Americans, but the importance, for African Americans, of reading writings by African Americans. This is, of course, an important claim, but it obscures the specific inflections of various of the pieces collected here: many of the early writers are arguing for access through literacy to the general body of works available in English (beginning with Christian scriptures and other religious writings and the constitution and laws of the United States), while other of the works attest to the importance of encounter with authors beyond the African American tradition (e.g. Martin Luther King Jr.'s account of the transformative impact of his reading of Thoreau and Gandhi or Stokely Carmichael's description of his wide reading ["With Olympian impartiality, I read everything and anything"] and his formal education in Latin and the tradition of "the Western Enlightenment" [118, 122]). The texts collected in the anthology are clearly a paean to the importance of reading and writing (their informing of one's sentiments, thoughts, words, actions); they are, more variably, a call specifically to engage with "our own" tradition—as is the case in the editor's introduction, Giovanni's foreword, and in some of the selections (e.g., W.E.B. Du Bois's cataloguing in 1913 of writings produced by persons of African descent in America, from Phillis Wheatley to Booker T. Washington [42-45], or Malcolm X's injunction to black boys playing dice outside the building housing the Schomburg Collection in New York City that they should be inside the library, which has "damn near everything ever written by or about black people," "learning about yourself, your people, and our history" [as recounted by Stokely Carmichael] [123-24]).

● The interplay between reading as a way of finding or affirming one's own identity and one's community of belonging, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, as a way of broadening one's horizons and breaking the provincialism and insularity of one's own experience and outlook is well dramatized in Oliver's discussion of Barack Obama and the role of reading in his life: Michiko Kakutani, discussing Obama's memoir "Dreams from My Father" in the New York Times in 2009 ("From Books, New President Found Voice"), remarks that in the memoir Obama "recalls that he read James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and W.E.B. Du Bois when he was an adolescent in an effort to come to terms with his racial identity"—but the memoir also "suggests that throughout his life he [Obama] has turned to books as a way of acquiring insights and information from others—as a means of breaking out of the bubble of self-hood and, more recently, the bubble of power and fame" (xxiv). As Obama himself remarked in 2016 at the funeral of former Israeli president and prime minister Shimon Peres, their relationship drew on their shared love for "words and books and history" and "beyond that, I think our friendship was rooted in the fact that I could somehow see myself in his story and maybe he could see himself in mine" (xxiv). Is this a claim of mutual identification based on similarities between their two "stories"? Or is it a suggestion that however different our experiences, there are enough commonalities in human lives and experiences, that we can find points of contact where we least expect to find them (but to do so, we first have to take an interest in lives different from our own)?

-

Publisher's description

-

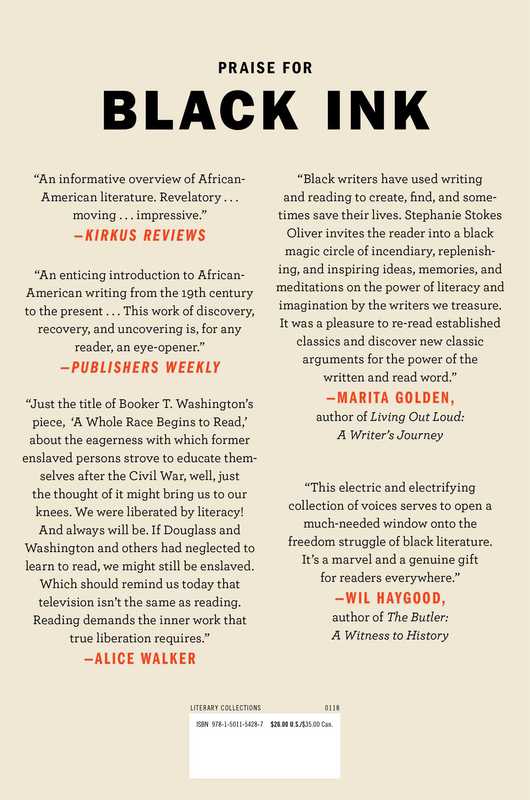

The copy on the back cover consists of extracts from two early reviews and blurbs from three African American authors:

● "An informative overview of African-American literature. Revelatory . . . moving . . . impressive."

—Kirkus Reviews

● "An enticing introduction to African-American writing from the 19th century to the present . . . This work of discovery, recovery, and uncovering is, for any reader, an eye-opener."

—Publishers Weekly

● "Just the title of Booker T. Washington's piece, 'A Whole Nation Begins to Read,' about the eagerness with which former enslaved persons strove to educate themselves after the Civil War, well, just the thought of it might bring us to our knees. We were liberated by literacy! And always will be. If Douglass and Washington and others had neglected to learn to read, we might still be enslaved. Which should remind us today that television isn't the same as reading. Reading demands the inner work that true liberation requires."

—Alice Walker [Walker is one of the authors included in the volume]

● "Black writers have used writing and reading to create, find, and sometimes save their lives. Stephanie Stokes Oliver invites the reader into a black magic circle of incendiary, replenishing, and inspiring ideas, memories, and meditations on the power of literacy and imagination by the writers we treasure. It was a pleasure to re-read established classics and discover new classic arguments for the power of the written and read word."

—Marita Golden, author of "Living Out Loud: A Writer's Journey"

● "This electric and electrifying collection of voices serves to open a much-needed window onto the freedom struggle of black literature. It's a marvel and a genuine gift for readers everywhere."

—Wil Haygood, author of "The Butler: A Witness to History"

● The copy on the front dust jacket flap reads: "Courageous, at times haunting, and sometimes profoundly humorous, "Black Ink" is an unprecedented anthology that brings together iconic literary talents from across the generations. In all of American history, black people were the only group ever to be forbidden by law to learn to read. This unique collection sheds light on that injustice as well as the hard-won literary progress made, assembling into one magnificent volume some of America's most cherished voices in a rich and vibrant conversation that presents reading—and writing—as an act of resistance.

"Spanning more than 250 years, "Black Ink" traces black literature in America from Frederick Douglass to Ta-Nehisi Coates and Roxane Gay in a masterly collection of twenty-five moving essays on the power of the written word. The book is organized into three sections: The Peril, The Power, and The Pleasure. With an array of contributors both classic (W.E.B. Du Bois, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin) and contemporary (Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Marlon James), "Black Ink" presents the brilliant diversity of black thought in America while underscoring the importance of these writers within the greater context of the nation's literary tradition."

● The back flap of the dust jacket includes a picture and biographical note on the editor, Stephanie Stokes Oliver, memoirist and former magazine editor at "Essence" and then at "Heart & Soul" magazine.

-

Anthology editor(s)' discourse

-

● Dedication: "For the ancestors, for you, and for the readers, writers, and thinkers to come"

● Oliver says the purpose of the anthology is to help document "the struggle for full literacy among African Americans" after their exclusion from reading and writing during the era of slavery (xviii); the pieces collected here "explain to us the struggle and the joys of overcoming the challenges of reading and writing" (xix).

● The anthology is intended as "a satisfying sampler of pieces that may motivate the reader to dig deeper and check out the original books" excerpted here, "as well as to explore additional Black authors and essays not included," rather than to provide "a multivolume comprehensive work" (xviii). [The aim of leading readers onwards might have been aided, however, by providing references to other writings germane to the topic addressed by the anthology.]

● "Within the larger American literary tradition, Black voices are often marginalized or included as tokenism. Here, they are front and center, loud and clear, humble and proud, humorous and dead serious" (xx).

● Oliver notes that the authors represented here, while all located in the United States for some portion of their careers, also engage the wider terrain of Africa and the black diaspora. Some left the USA "for a place that felt more like home elsewhere": e.g., W.E.B. Du Bois (Ghana), James Baldwin (France), or Stokely Carmichael (who was born in Trinidad, grew up in New York City, and "made his transition in Guinea, in West Africa"); others moved to the USA from elsewhere: e.g. Jamaica Kincaid (Antigua), Junot Díaz (Dominican Republic), Edwidge Danticat (Haiti), Marlon James (Jamaica), and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Nigeria) (xx). Oliver herself, one might note, was born in Seattle and lived most of her life in the United States, but now lives in Anguilla in the Caribbean ("About the Editor," 245).

-

Reviews and notices of anthology

-

● "Publishers Weekly" (30 Oct. 2017): "Without the weight of a hefty textbook, this anthology acts as an enticing introduction to African-American writing from the 19th century to the present. . . . This work of discovery, recovery, and uncovering is, for any reader, an eye-opener."

● "Kirkus Reviews" 85.21 (1 Nov. 2017): 1. "Revelatory, often moving essays by impressive writers"--though most of the selections are not, in fact, "essays" but "excerpted from longer works"; "Oliver's cogent author introductions contextualize each piece, making the anthology an informative overview of African-American literature."

● Stewart, Kate. "Library Journal" 142.20 (1 Dec. 2017): 111. Stewart notes that the works included "range from memoirs on the power of reading during slavery and emancipation to narratives of how certain books and authors shaped these writers' lives and straightforward advice on composition; all address the centrality of literacy to black liberation, both personally and politically. . . . In an effort to be tight and fast-moving, some samples feel disjointed excerpted from their original books, and the very brief introductions to each piece are at times lacking in necessary historical context. But taken as a whole, this survey of what it means to be a black reader and writer is an important and long overdue project."

● Daniels, Theo. "Ebony" 73.4 (Feb. 2018): 90. Brief (one paragraph) notice; remarks that the book includes selections from many of the best-known African American writers.

● Schlichenmeyer, Terri. "Cover to Cover." "Pittsburgh Courier" 11 Feb. 2018. Web.

https://newpittsburghcourieronline.com/2018/02/11/cover-to-cover-black-ink-literary-legends/

Emphasizes, as do other notices, the anthology's focus on the denial of the power of literacy to enslaved African Americans and the testimonies of African Americans, from the era of slavery to the present, to the world-enhancing power of literacy in their lives--but offers very little by way of review beyond illustrative summary of the contents. Concludes with the statement, "the essays you'll find in here will make bookworms want to stand up and cheer," thus underlining the anthology's appeal to all readers, not only African American ones.

● Catterall, Sara. "Shelf Awareness" 16 Feb. 2018. Weekly e-newsletter.

http://www.shelf-awareness.com/readers-issue.html?issue=689#m12094

Catterall notes that this is the third anthology prepared by Stephanie Stokes Oliver (the editor) and remarks that the selections in the anthology provide "a chronological portrait of the conscious development of black literature in the U.S. by black writers, editors and critics"

-

References

-

● Oliver writes in her introduction, "I graduated the year that Toni Morrison edited the groundbreaking historical collection "The Black Book" (an inspiration for this anthology)" (xx-xxi)

-

Black Book

Black Book

-

● The selection from Terry McMillan ("New Black Scribe") is an excerpt from her introduction to the anthology she edited, "Breaking Ice" (1990).

-

Breaking Ice: An Anthology of Contemporary African American Fiction

Breaking Ice: An Anthology of Contemporary African American Fiction

-

See also

-

● The editor, Stephanie Stokes Oliver, is the daughter of Charles M. Stokes (1903-1996), a lawyer, politician, and district judge in Seattle, who remained loyal to the GOP as the "party of Lincoln" (though his daughter subsequently left the fold): her memoir, "Song for My Father: Memoir of an All-American Family" (2004), was reviewed by Angela D. Dillard in the "Seattle Times" 12 Oct. 2004.

-

Seattle Times

-

● Although Oliver does not provide references to scholarship on the theme of her anthology, one might consult such works as the following on literacy under conditions of slavery and hard-wrought emancipation: (given in chronological order):

● Woodson, Carter. "The Education of the Negro prior to 1861: A History of the Education of the Colored People of the United States from the Beginning of Slavery to the Civil War" Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1919.

● Webber, Thomas L. "Deep Like the Rivers: Education in the Slave Quarter Community, 1831-1865." New York: Norton, 1978.

● Cornelius, Janet Duitsman. "'We Slipped and Learned to Read': Slave Accounts of the Literacy Process, 1830-1865." Phylon 44.3 (1983): 171-86.

● Cornelius, Janet Duitsman. "'When I Can Read My Title Clear': Literacy, Slavery, and Religion in the Antebellum South." Columbia: U of South Carolina P, 1991.

● Dalton, Karen C. Chambers. "'The Alphabet Is an Abolitionist': Literacy and African Americans in the Emancipation Era." Massachusetts Review 32.4 (Winter 1991): 545-80.

● Harris, Violet J. "African-American Conceptions of Literacy: A Historical Perspective." "Theory into Practice" 31 (1992): 276-86.

● Fox, Tom. "From Freedom to Manners: African American Literary Instruction." "Forum" 6 (1995): 1-12.

● Logan, Shirley Wilson. "Literacy as a Tool for Social Action among Nineteenth-Century African American Women." "Nineteenth-Century Women Learn to Write." Ed. Catherine Hobbs. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1995. 179-96.

● Casmier-Paz, Lynn Anne. "The Effects of Literacy in English-Language Slave Narratives." Diss. U of Pittsburgh, 1998.

● Gundaker, Grey. "Signs of Diaspora/Diaspora of Signs: Literacies, Creolization, and Vernacular Practice in African America." New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

● Monaghan, E. Jennifer. "Reading for the Enslaved, Writing for the Free: Reflections on Liberty and Literacy." Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 108.2 (Oct. 1998): 309-41.

● Williams, Heather Andrea. "'Clothing Themselves in Intelligence': The Freedpeople, Schooling, and Northern Teachers, 1861-1871." "Journal of African American History" 87 (2002): 372-89.

● Richards, Jeffrey H. “Samuel Davies and the Transatlantic Campaign for Slave Literacy in Virginia.” "Virginia Magazine of History and Biography" 111 (2003): 333-78.

● Belt-Beyan, Phyllis M. "The Emergence of African American Literacy Traditions: Family and Community Efforts in the Nineteenth Century." Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004.

● McPhail, Irving Pressley. "On Literacy and Liberation: The African American Experience." "Teaching African American Learners to Read: Perspectives and Practices." Ed. Bill Hammond, Mary Eleanor Rhodes Hoover, and Irving Pressley McPhail. Newark, DE: International Reading Association, 2005.

● Monaghan, E. Jennifer. "Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America." Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 2005.

● Span, Christopher M., and James D. Anderson. “The Quest for ‘Book Learning’: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom.” "A Companion to African American History." Ed. Alton Hornsby Jr. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. 298-309.

● Williams, Heather Andrea. "Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom." Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2005.

● Bly, Antonio T. "Breaking with Tradition: Slave Literacy in Early Virginia, 1680-1780." Diss. College of William and Mary, 2006.

● Gundanker, Grey. "Hidden Education among African Americans during Slavery." "Teachers College Record" 109.7 (July 2007): 1591-1612.

● Logan, Shirley Wilson. "Liberating Language: Sites of Rhetorical Education in Nineteenth-Century Black America." Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2008.

● Moss, Hilary J. "Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America." Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2009.

● Watson, Shevaun E. “’Good Will Come of This Evil’: Enslaved Teachers and the Transatlantic Politics of Early Black Literacy.” "College Composition and Communication" 61 (2009): 66-89

-

● Literacy as Freedom (Smithsonian Institution, 2014)

-

● Green, HIlary. "Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1890." New York: Fordham UP, 2016.

● Baumgartner, Kabria. "In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America." New York: New York UP, 2019.

● Zehnder, Madeline. "Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Media Theorist." "Common-place" (Dec. 2021). Web. [A discussion of Harper's poem, "Learning to Read," from "Sketches of Southern Life" (1872)]

-

Common-place: The Journal of Early American Life

-

Type of anthology

-

● Intended readership: general audience.

● Status of contents: reprinted materials, except for the introduction by the editor and the foreword by Nikki Giovanni

● Genre of contents: nonfictional prose (essays and excerpts from life writings—slave narratives, autobiographies, and memoirs—and one interview)

● Identity of authors included: 26 selections (including foreword), 16 by men and 10 by women

● Identity terminology used: both "Black" and "African American": e.g., "Black" (title); "Black authorship" (xiii); "Black Lives Matter" (Nikki Giovanni, xvi); "African Americans" (xviii); "Black parents" (xviii).

● Period covered: 1845 to 2017. Although the first section is designated as covering the period from "1800-1900," the actual selections included in the anthology begin with excerpts from Frederick Douglass's "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass" (1845) and from Solomon Northup's "Twelve Years a Slave" (1853).

-

Item Number

-

A0454

Black Book

Black Book

Breaking Ice: An Anthology of Contemporary African American Fiction

Breaking Ice: An Anthology of Contemporary African American Fiction

Black Book

Black Book